Argentina needs to arrest the high inflation that is hindering the development of long-term capital markets. Jason Mitchell reports.

Argentina’s short-term credit is growing dramatically, but the country needs to reduce its inflation rate markedly if longer-term credit is to take off.

Personal loans, short-term loans to companies and credit card loans have all reached record levels, but mortgage lending is still below its 2002 peak.

Analysts say that the country’s high inflation rate (officially 8.5%, but estimated by local economists at between 15% and 20%) is preventing the development of long-term capital markets. Reducing inflation is probably the greatest challenge facing Cristina Kirchner, who took over as president from her husband, Néstor, on December 10, 2007.

At the time of the change in president, the stock of loans to the private sector was 107bn pesos ($34bn) against 30.3bn pesos in September 2003, the lowest level reached following the country’s 2001 economic meltdown. In January 2000, the total stock was 66bn pesos.

However, despite rapid growth over the past two years, the stock of mortgages was 14.5bn pesos in December last year against a peak level of 21bn pesos in February 2002.

Long-term troubles

Daniel Artana, chief economist at Argentine economic consultant Fiel, says: “Most banks in Argentina are lending on the basis of sight deposits or time deposits of fewer than 50 days. That makes long-term lending much more difficult.

“At the end of 2006, mortgage lending to companies with interest rates indexed to inflation started, but the government effectively killed it off when it interfered in INDEC, the federal agency that reports the figures.”

He adds that Chile developed inflation-indexed mortgage lending in the 1980s despite inflation rates of between 15% and 20%, but that for this to work in Argentina, a stable inflation rate would have to be given (which since the INDEC intervention it is not).

“The slow development of an mortgage-backed securities (MBS) market in Argentina is primarily due to the preponderance of short-term credit in the local market,” says Magda Guillen, Latin American structured products research analyst at Merrill Lynch.

Asset-backed securities

Several high-profile retail stores, finance companies and banks have used asset-backed securities (ABS) as the main funding source for their lending. Local institutions have an appetite for ABS issuance, especially if it involves low-risk investments – something scarce in current markets – but are not prepared to make any longer plays.

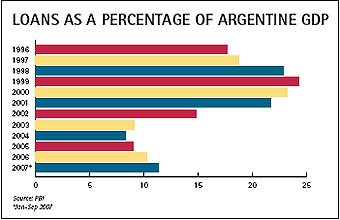

Against gross domestic product (GDP), the stock of loans to the private sector in Argentina has grown markedly since the crisis (compared with historical levels and those of other countries it remains low). It is 11% today against a peak of 24% in 1999 and a low of 8% in 2004 (see chart).

The stock of residential mortgage loans against GDP today is only 1.4% against a peak of 4% in 2001.

The country’s economy has been booming for the past five years with an average annual economic growth of 8.5%. Argentines have been feeling much more confident and have been prepared to purchase durable goods and cars with personal loans, credit cards or store cards.

In particular, the agricultural sector has been performing remarkably well, on the back of soya exports to China and a doubling of soya prices during the past year from 580 pesos or $183 a ton to 1000 pesos or $317 a ton.

Bad debts

The country has twin budget and trade account surpluses, bad debts at a historically low level of 3%, and record Central Bank reserves of $47bn.

However, Ms Guillen says: “Heavy-handed government intervention has distorted these [positive outcomes], particularly in light of the previous Kirchner administration’s use of price pacts and heavy state spending to spur economic growth.”

Furthermore, the country is not experiencing the kind of investment boom seen in Brazil, because it lacks the longer-term capital markets of its larger neighbour. The mutual funds industry in Argentina is worth only $8bn, compared with $525bn in Brazil; Argentina’s private pension funds amount to just $30bn compared with $212bn in Brazil.

“It is very difficult for Argentines to have confidence in the government; there is no long-term confidence in the peso, so people are not prepared to save,” says Maximiliano Col, director of economic research at state-owned bank Banco Ciudad. “Macroeconomic stability is the key to long-term capital markets. There are no short cuts.”

Careful management

“Things must progress slowly with responsible economic management and low inflation. The Central Bank must be independent and people must trust the government’s policies.”

One reason Argentina has not been able to develop an MBS market – the outstanding stock of MBSs is only $200m – is that lenders can rely on deposit accounts as mortgage penetration is so low. However, banks will probably exhaust this funding source by next year.

Mortgage lending roared ahead in 2006 and 2007, but lenders had to raise their mortgage rates sharply following the subprime crisis in the US, which killed off new origination because people could not afford the rates.

According to Banco Hipotecario, one of the country’s biggest mortgage providers, its lending for the first nine months of 2007 was up by 350% on the same period of 2006. Its 20-year mortgage, fixed at 9.75%, had been popular, but the bank had to pull it when the subprime crisis erupted.

Today, it has no products of that duration and is marketing a 10-year mortgage fixed at 17.25% and a five-year mortgage fixed at 15% (the benchmark 30-day peso prime rate stands at 14%, up from 9.6% a year ago).

Banco Hipotecario chief executive Clarisa Estol says the country has no long-term funding for mortgages “because it’s Argentina”.

The bank started doing some MBSs in 1996, but the 2001 economic crisis put the brakes on this, and Hipotecario was only able to resume securitisations in 2004. However, the subprime crisis in the US closed the window again, and the bank would now have to pay a high interest premium on MBSs because of uncertainty about the country’s inflation rates.

“What is the country’s inflation rate? No one knows,” Ms Estol says.

Merrill Lynch’s Ms Guillen adds: “Argentina’s capital markets are under pressure from both external and internal factors, and the addition of the subprime crisis will certainly underscore the need to address these issues.”

She adds that during the past year, several factors, including INDEC intervention, fuel shortages and protracted wage negotiations with unions, “pushed coupons for domestic consumer and credit card-backed transactions to some of their highest levels in recent memory, while jittery international markets have increased volatility of Argentine government bond spreads and credit default swaps”.

In January, the country led losses among emerging markets on news of the Fed’s unexpected rate drop, highlighting lingering international uncertainty over the soundness of Argentina’s surging domestic economy.

Steady growth needed

Ms Guillen says Argentina could develop a future MBS market but this depends on its ability to maintain macroeconomic stability, deliver steady GDP growth, and allow local markets to price goods and services fairly and transparently.

Demand for MBS would likely be high, but current spreads on longer-term transactions mean mortgage-backed issuance would be unaffordable for most issuers at today’s rates.

Furthermore, Argentines hold up to $200bn outside the country and still do not trust local banks or capital markets enough to return their wealth.

Fabián Bellettieri, treasurer at Argentine investment bank MBA, says: “Currently, local pension funds will not touch mortgages. They may have to invest in them in the future because of political pressure.

“It would take little effort to improve the long-term capital markets but we are a long way from getting the government to do this. Brazil, Chile and Peru are managing it. All that is required is a transparent consumer price index; it just depends on the willingness of Ms Kirchner’s government to establish it.”

Reasons for optimism

However, Fabián Rodriguez, a director of Banco de la Provincia de Buenos Aires, a state-owned bank, says: “The country faces a great opportunity. I am optimistic about the country’s ability to develop long-term capital markets because of five years of solid macroeconomic stability, something which the country previously lacked.”

Argentina is at a crossroads. There is talk of an ‘Argentine economic miracle’. As long as China remains booming and commodity prices stay high, many economic sectors will perform exceptionally well.

However, for wealth to start cascading through all industries and all echelons of society, long-term capital markets are vital. To develop them, the government must establish a credible agency to measure inflation, stabilise inflation rates, and then cut them drastically.