Top Islamic banks ranking, 2013: Finding quality growth

Islamic banks are growing more quickly than their conventional counterparts, but not all of this growth is generating good returns.

In August 2013, the Malaysia International Islamic Financial Centre (MIFC) produced a report that boldly predicted Islamic finance (both banks and capital markets) could double in size from assets of about $1600bn today, although no timescale was suggested. In particular, the report assumed that exports and imports for the 57 states that belong to the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) would increasingly be funded by Islamic rather than conventional finance. Trade finance is well suited to sharia-compliant structures, because it is backed by real economic flows.

More from this report

- Slower and steadier: the new stage of Islamic finance

- Noor CEO's big ambition for Islamic finance

- The Islamic liquidity management quest

- Spreading the sharia success story

- Islamic project financing: a health check

- Islamic banks weather the storm

- Where does asset management fit in the Islamic finance picture?

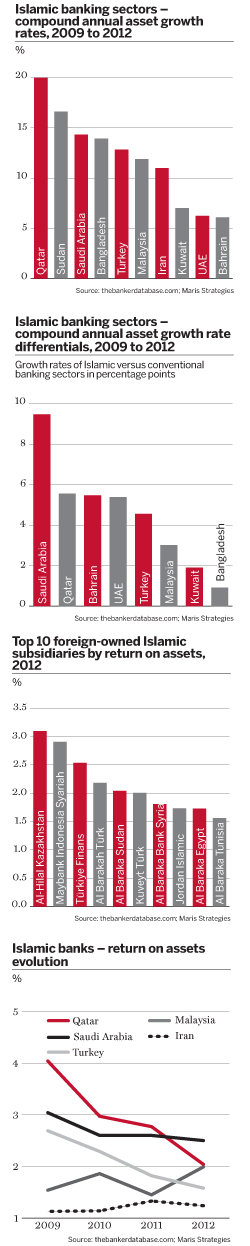

There is no question that Islamic banks are outgrowing their conventional counterparts in most major markets. Among the major Islamic banking markets (excluding Iran and Sudan, where all banks must be sharia-compliant), the compound annual growth rate for assets from 2009 to 2012 inclusive was 11%. By contrast, the compound annual growth rate for conventional banks in the same markets was 6.8%.

Growth in Islamic and conventional banking sectors remains correlated in many countries. Qatar has the highest growth rate for both sectors, and Bahrain the lowest. But in both those countries, the Islamic growth rate is still significantly higher than that for conventional assets. And in certain countries, Islamic assets are clearly less correlated. In particular, Saudi Arabia has one of the slower growing conventional banking sectors, but a fast-growing Islamic finance industry. Official encouragement may well play a part here, something recognised by the MIFC in a September 2013 report.

Lacklustre profits

However, rapid growth is not always high-quality growth. In the case of Islamic banks, profits have certainly not grown in line with assets. The aggregate return on assets (ROA) for Islamic banks in The Banker's sample was 1.51% for the four years 2009 to 2012 inclusive. By contrast, the ROA on conventional banks in the same countries was 2.12%.

This underperformance is by no means uniform. In Bangladesh, heavy losses at the country’s two largest conventional banks in 2012 mean the sector’s compound annual growth rate for pre-tax profits from 2009 to 2012 is minus 17%. By contrast, the country’s Islamic banks have seen a compound annual growth rate for pre-tax profits of more than 14% over the same period. In Bahrain, conversely, Islamic banks suffered heavy losses in 2009 and 2010, whereas compound annual profits for the conventional banking sector were growing more than 8%. Overall, Islamic banks have outperformed in Malaysia and marginally in Saudi Arabia, while underperforming in Turkey and heavily underperforming in Qatar.

Perhaps the most acute concern for the industry would be the general trend for profit growth to fail to keep up with asset growth in many of the major markets for Islamic finance. Only in Malaysia and the United Arab Emirates has there been a clear tendency for return on assets to improve over the past four years – together with Bahrain, where the sector has recovered from losses. Results are also improving significantly in Egypt, but this is still a small Islamic finance market – sharia-compliant assets account for just 4.3% of total Egyptian banking assets. In markets such as Iran and Kuwait, ROA is trending sideways, while in Qatar, Saudi Arabia and Turkey there is a clear descent in profitability.

The speed of Islamic asset growth in Qatar, Saudi Arabia and Turkey may go some way to explaining the decline in ROA, as greater competition begins to erode margins. But it seems unlikely to be the whole explanation. Qatar’s conventional banking assets are also growing rapidly, yet the compound annual growth rate for profits over 2009 to 2012 was more than 14%, compared with just 1% for Islamic profits. And in Turkey, although growing quickly, the Islamic banking sector is still underdeveloped, at just 3% of conventional banking assets. That should leave plenty of room for everyone to expand without hitting performance.

Choosing models

In practice, declining profit growth in the more established markets may simply represent a gradual maturing of a sector that enjoyed exceptionally high profitability a few years ago. Although declining, aggregate ROA for Islamic banks in Qatar and Saudi Arabia over the past four years still exceeded that of conventional banking, and these remain the two most profitable Islamic banking markets aside from the very underbanked Sudanese and Bangladeshi economies.

Meanwhile, the performance of Islamic banks in Turkey is simply overshadowed by a very successful conventional banking sector. The aggregate ROA for Turkish Islamic banks is more than 2%, but this is eclipsed by a conventional sector enjoying ROA of 2.49% over the period 2009 to 2012 – beaten only by Bangladesh in our sample.

In fact, Turkey remains a highly attractive market for Islamic banking given the sector’s very small size compared to conventional banks. Gulf-based banking groups are enjoying some of their best returns via Turkish Islamic banking subsidiaries. Among the 10 most profitable foreign-owned subsidiaries in the Islamic financial institutions rankings, three of them are based in Turkey, more than any other country.

Türkiye Finans Bank is owned by Saudi Arabia’s National Commercial Bank, which is the largest Saudi bank. It operates an Islamic window that accounts for the second largest pool of sharia-compliant assets after the pure-play Islamic bank Al-Rajhi. Bahrain-based Al Baraka also owns a Turkish subsidiary, while Kuwait Finance House owns Kuveyt Türk. Al Baraka’s network accounts for half of the top 10 most profitable foreign subsidiaries, although some of these are small operations in frontier markets such as Syria and Sudan.

The two best-performing foreign subsidiaries are the Kazakh operation of UAE’s Al-Hilal and Malaysian Maybank’s Indonesian subsidiary. Al-Hilal benefits from being the only Islamic bank in the country, and from the timing of its entry – it began operations just after a real estate crash that had saddled local lenders with legacy portfolios of bad assets. By contrast, Maybank is performing well in a much more competitive market, with 10 sharia-compliant banks, 44 Islamic windows (many of them insurers rather than banks) and three foreign subsidiaries. Aggregate ROA in Indonesia in 2012 was 1.6% for Islamic financial institutions, which is not much more than half the rate for conventional banks in the same year – Indonesia is one of the most profitable markets in the world for conventional banking.

Subsidiary issues

Overall, assets held by foreign subsidiaries in the ranking are only about 6% of the total in the ranking. Among those subsidiaries that are wholly sharia-compliant, aggregate ROA is 1.2%, compared with 1.4% for domestically owned Islamic banks.

We have long observed the difficulty of comparing the performance of wholly sharia-compliant banks with Islamic windows. This is because most windows do not report separate profit data, which is instead consolidated into the parent bank’s performance. However, regulations in Malaysia mean that windows of some Malaysian banking groups have now been incorporated as separate subsidiaries, enabling a comparison of profitability. On this basis, it appears that the window model was less successful in 2012. The ROA among 22 fully sharia-compliant banks with assets of $96bn is 1.7%, while that among three windows that report separately, with assets of $44bn, is 1.11%. The three windows were part of some of Malaysia’s largest and best-known banking groups: Maybank, CIMB and RHB.

While this outcome may not necessarily be representative of the performance of Islamic windows in other markets, Malaysia is important as the third largest Islamic finance market (after Iran and Saudi Arabia), and perhaps the most developed in terms of products and regulation. Without more in-depth data, it is not possible to reach firm conclusions on why windows are underperforming in Malaysia. But this outcome suggests the Islamic subsidiaries are not deriving significant efficiency savings or cross-selling opportunities from operating alongside a large conventional banking platform.