Although much has changed in the world of banking since 1926, many of the same challenges remain.

It is no great surprise that the definition of a bank offered in the first issue of The Banker in January 1926 no longer rings true. Contributor Sir D Drummond Fraser, in protest at what he claimed was the “loose way” in which the term was often used, defined banks as “institutions where a substantial part of such business consists of the receipt of money on current account to be drawn upon by cheque”.

The wider subject of Sir Drummond Fraser’s article ‘Are bank fusions advantageous?’, where he discusses the merits and drawbacks of banking consolidation, probably rings a more familiar note. Although much has changed within the world of banking over the past 95 years, many of the same challenges remain.

Technology, and the innumerable ways in which it has changed the way the business of banking is done, is indisputably the most tangible area of change since 1926. In the early days of The Banker, the humble bank branch was in its heyday — a focal point of activity. The primary importance of banks’ buildings in that era is reflected in recurring features on the architecture of bank branches, as well as head offices, which appeared in the magazine until well into the 1940s.

In the early days of The Banker, the humble bank branch was in its heyday — a focal point of activity

Attitudes about the role of bank offices and branches have certainly moved on considerably. In an essay for The Banker’s first issue, CH Reilly (head of the Liverpool School of Architecture), declares his admiration for C Hoare and Co’s bank in London — one of the oldest in the world — as it has sleeping quarters above its offices, to enable bankers to continue the practice of living above their premises. He writes: “We have the case of Messrs Hoare’s bank in Fleet Street — the best piece of architecture in that street — where one of the junior partners, taking it in turns, always resides over the banking premises.”

Bank branches clearly no longer occupy the same central role, with shrinking bank networks often a feature in a modern bank’s strategy. Société Générale is just one of the latest banks to announce a large-scale closure programme, as a result of its planned merger with subsidiary Crédit du Nord, with 600 branches in its network due to close by 2025. However, the complete demise of the bank branch has often been predicted prematurely. For instance, research by McKinsey in 2018 across 15 economies in Asia-Pacific found that up to 20% of banking transactions were still done in branch, suggesting their role is far from redundant.

Automating the cheque

Returning to Sir Drummond Fraser’s 1926 definition of what a bank is, and the central role of the cheque, here too there has been monumental change. As the article ‘First steps to electronic banking’, published in The Banker in April 1957 makes clear, processing the mountain of cheques which previously came through a bank’s doors every day used to be a heavy administrative burden: “The heart and centre of the banking system is the cheque … many hundreds of millions of cheques are drawn in a year, and the banking machine is primarily occupied with their handling.” According to the 1995 book, Waves of Change, published by Harvard Business School Press, almost 30 million cheques were being written each day in the US by the early 1950s; although some mechanised processing existed by this stage, much of the process of handling those cheques would have still been manual.

The possibility of automating cheque processing is rightly flagged by the article as one of the earliest examples of electronification being able to have a substantial impact on the banking industry. The article also begins to hint at the possibilities that an “electronic brain” may be able to offer in terms of “bookkeeping, including ledger-posting, preparation of customers’ statements and totalling of each day’s work … continuous calculation of the balances on accounts and debit and credit totals, as well as balances of all items handled … that will store all the relevant data, in its ‘memory’, and release particular information as required”. Substantial labour-saving and the possibility of centralisation of processing functions were already touted as the potentially huge benefits of this technology.

The thorny issue of whether technological change would lead to lower costs, and ultimately lower charges for customers, is also raised, with the astute observation: “Eventually, there may indeed be very real savings … but there are so many threatening possibilities of other pressures on bank revenues to offset these savings that no banker is likely to be at all hopeful that he will be able to bring his charges down as a result of them.”

Innovation in cheque processing did indeed arrive with the widespread adoption of magnetic ink character recognition code technology in the years following the April 1957 article, paving the way for much quicker processing. Several years earlier, another major milestone had been reached in 1950 with the launch of Diners Club — widely regarded as the first modern, general purpose, credit card (although it was technically a charge card). By the 1970s, credit cards were relatively common, although the notion of payment cards directly linked to customers’ bank accounts was still some way from being realised.

Electronic money

Introducing debit cards, although long-talked about, was far from a straightforward exercise. A March 1982 article in The Banker, titled ‘Space Invaders in the banks’, assessed developments in the technology that underpins many debit card transactions, electronic funds transfer at point of sale (EFTPOS). It states: “The idea of EFTPOS means, in effect, electronic money or the cashless society is a very old established dream. But how close is it to reality? The pattern in Europe and the US is markedly different.”

The article compares efforts in experimenting with the technology in the US — where banks were still heavily restricted from operating outside of their home state, and therefore such experiments were restricted to one or two large local retailers — with those in Europe, where banks did not face such limits on their activities.

In the US, it observes: “Looking at the literature on EFTPOS, it sometimes seems that each … bank has conducted an EFTPOS experiment in conjunction with its local supermarket or major retailer, and all with similarly inconclusive results. The hard fact is that there is still too little evidence of the commercial viability of such systems for the banks and the retailers to show great enthusiasm.”

But Europe, it suggests, “with its smaller number of powerful banks operating nationally and internationally, and with country-wide retail concerns, is a more natural contender for the honour of installing the first national EFTPOS network”. It reports that “the best-known experiment in Europe involves the Crédit Agricole group of rural banks and the Euromarché hypermarket in Limoges. Crédit Agricole seems pleased enough with the results to plan to install a further 30,000 point-of-sale terminals throughout France in the next five years.”

Debit cards are, of course, now a mainstay of the global payments and banking system. For instance, according to Federal Reserve data, they have been the most popular non-cash payment method in the US since 2007. Looking ahead, however, non-card digital payments, such as the digital wallet and QR code-based systems popular in China, could be a significant disruptive force in the coming decades.

Genuine substitute for human tellers

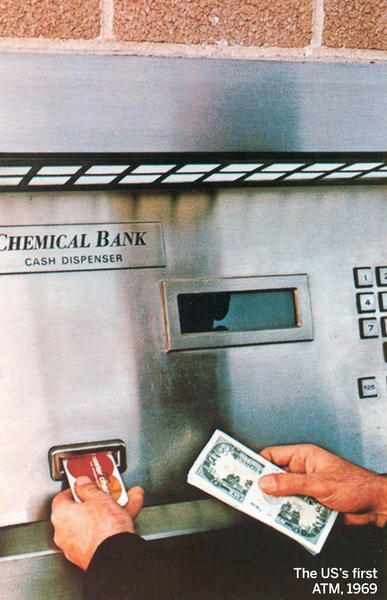

In the early 1980s, expanding ATM networks were also still a cutting-edge issue, although the US was a clear leader in the field. By the time of The Banker’s March 1982 issue, there were more than 17,000 ATMs installed in the US. There is some debate about when the first ATM was launched: Barclays had introduced a cash dispensing machine in a suburb of North London in 1967, often regarded as the world’s first ATM, but its use required the purchase of one-time-use, prepaid vouchers. Chemical Bank’s installation of an ATM in New York 1969, which used reusable, magnetically-coded cards moved the technology forward to something more closely resembling modern ATMs.

By 1982, The Banker’s view was that Japanese-built machines were the best in class, remarking: “ATMs have probably been developed to the highest pitch by the Japanese. There, they are a genuine substitute for human tellers. Japanese banking halls are lined with ATMs looking like rows of telephone booths. They both deliver cash and accept it. Japanese businessmen take out what they think they will need at the beginning of the day, and return what they have over at the end.”

According to data from research body, RBR, as of 2019 there were 3.23 million ATMs globally — a slight decrease on the 3.25 million in 2018. Although their numbers are decreasing in certain markets (notably China which removed 30,000 ATMs between 2018 and 2019), this is being offset by increases in other markets, such as India and Egypt.

The same 1982 article also mentioned the nascent growth of what at the time was labelled “home banking”, which at that time consisted of using a television screen in combination with a telephone to conduct transactions such as checking an account balance or paying bills. The pace of technological change in both wholesale and retail banking since the 1980s has been non-stop; The Banker introduced its ‘Banking Tomorrow’ column in the early 1980s, and technology has been a core part of our coverage ever since.

Green is the new oil

If technological change has been a dominant force in shaping the banking industry over the past 95 years, the transition to a greener and more sustainable economy looks set to be a major driver in the coming decades. A recent paper from the Global Financial Markets Association and Boston Consulting Group, for instance, suggests that for the global economy to hit the climate change targets set out in the Paris Agreement, climate finance market structure — the ecosystem of market participants, products, instruments and market infrastructure for delivering sustainable finance solutions — must “grow at an unprecedented scale, speed and geographic scope”. Specifically, the report suggests that the volume of climate-aligned finance must reach $100-150tn over the next three decades.

The future for the oil industry in this context, a defining part of economic and technological advancement during 20th century, looks highly uncertain. Although in the short term, oil demand is expected to continue increasing (following a recovery from coronavirus-induced slump) until around 2030, it is expected to dwindle thereafter, according to International Energy Agency forecasts.

Rewind 70 years and oil was the future. By the mid-1950s it was evident not only how much of a major driving force oil was within the global economy, having overtaken coal as the world’s most important energy source, but also that the Middle East was on course to disrupt the US’s dominance of the industry. In November 1956, The Banker produced a special report on Middle East oil describing it as the West’s ‘lifeblood’. In one chart, the article highlights how less than two decades earlier, in 1938, total global oil output stood at just 280.5 million metric tons compared to 795.3 million metric tons in 1955. The Middle East’s output in that time had increased tenfold from 16.2 million metric tons to 162.5 million.

The report reflects a world in which oil production was on the cusp of significant expansion, in large part driven by the Middle East, stating “the scope for the expansion of oil extraction shown in the Middle East, will be immense … The Sheikhdom of Kuwait alone, covering an area of only 6500 square miles, and containing a population of 200,000, boasts proved reserves well in excess of those proved in the US, which has been responsible for three-fifths of the oil produced in the world so far.” The article adds: “The special importance of the Middle East lies in the emergence of its abounding potential during this phase in which the demand for oil is expanding abnormally fast.”

Now, Middle Eastern nations have recognised the need to diversify their economies away from reliance on oil, perhaps most notably Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 strategy. In the US, under Joe Biden’s incoming administration, there is also debate about the outlook for the nation’s oil industry. But if in the long term there are question marks over oil, it remains a potent force within international trade and relations, and has been throughout the past 95 years.

Global co-operation

Reflecting on international trade and economic co-operation more broadly, it is fair to conclude there have been some notable advances in the past 95 years. One positive example is the co-ordinated action taken by central banks in March 2020 to calm the markets as coronavirus-induced uncertainty and dislocation really took hold. Decisive central bank action at this crucial moment is something which was welcomed by many bankers for its stabilising impact, and many remarked on the speed and decisiveness of interventions in comparison to the global financial crisis.

The subject of global co-operation before and during the global financial crisis (GFC) 2007-9 has generated much coverage in its own right. But in the context of Covid-19, the regulatory changes introduced in the aftermath of the GFC, although challenging and at times contentious, appear to have proved their worth in terms of improving financial stability.

While the process for establishing international banking standards, via the Bank for International Settlement’s (BIS’s) Basel process, will likely continue to generate considerable debate, the existence of the BIS itself is now a well-accepted and vital part of the international financial system. Ninety-five years ago it was still four years away from its May 1930 opening. In July 1929, The Banker was broadly supportive of the new institution, stating: “The new bank will become a meeting place of the heads of central banks and will facilitate co-operation between them. While up to now the movement towards co-operation was vague and abstract, it will gain a new concrete form through the establishment of the new bank.” And even though there was an expectation that “the new institution [was] bound to divert some business from the existing banks,” it was, The Banker concluded, “likely, however, that the advantages of greater stability will more than compensate the banks for their loss.”

The regulatory changes introduced in the aftermath of the global financial crisis… appear to have proved their worth in terms of improving financial stability

The BIS’s primary envisaged purpose had been overseeing German reparation payments following the First World War; however, with reparations paused in 1931 and then cancelled a year later, this role was to quickly fade in importance. What started as the secondary role of promoting central bank co-operation took prominence.

There had been some concerns at the time that the new institution’s remit would be too broad; however, in December 1929, an article in The Banker praised its organisation committee for giving it flexibility, stating “the experiment is entirely without precedent, and it would be inexpedient to bind the bank with too rigid rules, which would necessarily lack any foundation in practical experience … it was advisable to grant the board a certain freedom to adjust the activities of the bank to practical necessities as they arise in the course of experience.”

Given the challenges it would face in the years immediately following its creation, with economic crises and banking failures plaguing the 1930s, a flexible mandate proved necessity. The 1930s was a dark moment for the international financial system. But following the Second World War, with the establishment of the Bretton Woods monetary system, there was considerable optimism that the world was beginning a new era of international co-operation.

In a January 1946 article, ‘Towards an expanding world economy’, The Banker stated that the new system could “open the way to an entirely fresh start in international trade, with a worldwide lowering of trade barriers and international consultation in the conduct of commercial policy in place of chaos and economic nationalism”. Although the issues being argued over may be different, such language could easily be applied to more recent trade tensions such as US-China wrangling or EU-UK negotiations.