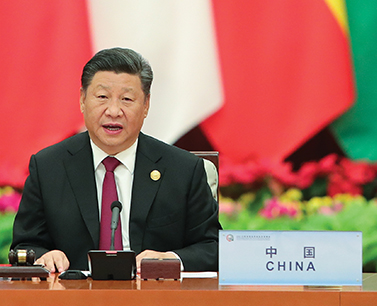

On September 3, 49 African heads of state descended on Beijing, China’s capital, for the triennial Forum on China Africa Cooperation (Focac). Presided over by Chinese president Xi Jinping, the forum mapped out the next phase of Chinese financial support for Africa’s development.

This year’s summit was the seventh iteration of the event, highlighting China’s growing role as a leading financier of global development in Africa and beyond. Mr Xi announced pledges totalling $60bn for the region, the same amount promised at the last Focac summit in Johannesburg, South Africa, in 2015.

The $60bn Africa pledge includes $20bn in new credit lines, $15bn in foreign aid (including grants, interest-free loans and concessional loans), $15bn for a special development financing fund and a $5bn import finance fund for products from Africa.

Touting a win-win scenario

“China believes that the sure way to boost China-Africa co-operation is for both sides to leverage its respective strength – and it is for both China and Africa to pursue win-win co-operation and common development,” Mr Xi told the forum. “In doing so, China follows the principle of giving more and taking less, giving before taking, and giving without asking for return.”

However, in some quarters there are questions as to whether this is strictly true. Across Asia, partners such as Sri Lanka, Pakistan and Malaysia are turning sour on projects with China, citing onerous financial burdens and poor development outcomes. Several have been cancelled, while the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has warned of debt burdens accumulated in developing countries as a product of China-led Belt and Road Initiative projects.

African leaders have also voiced concerns about the nature of their relationship with China. Mr Xi’s announcement of an import finance fund targeting the region is a new development in response to criticism of China’s ballooning trade deficit with African markets (having become Africa’s biggest trading partner in 2009, surpassing the US).

Some critics have accused China of predatory lending practices to developing countries in order to extend its influence, and using the state’s vast development financing capacity as its war chest in a global campaign.

Advocates for China, however, are adamant that investment in developing markets is simply a smart move and draws on the country’s experience of lifting some 800 million people out of poverty in the space of a few decades.

“Thirty years ago, most Chinese people in Europe, even scholars, were cleaning dishes. Today you go back to London you see there is a large [Chinese] middle class going to Louis Vuitton, to Chanel, buying a huge amount of luxury goods,” says Helen Hai, CEO of the Made in Africa Initiative. “This is the power of a rising middle class. [China] is not just helping its own country, it’s good energy for economic transformation globally.”

Economic diplomacy returns

As China emerges as a global power, its rise has been greeted by the West with a mixture of fascination and consternation. The US, in particular, is discomfited. For all of China’s talk of mutual 'win-win' co-operation, the American bet that two decades of liberalisation would produce a more democratic China has not materialised at the same time as US stature on the global stage has declined.

The intensity of that rivalry has heated up throughout 2018. In a national address in January, US defence secretary Jim Mattis made clear the administration’s displeasure with China’s current trajectory. “Great power competition – not terrorism – is now the primary focus of US national security,” he said, describing China’s militarisation of the South China Sea as a provocation.

Some believe China’s moves are a miscalculation. “China’s mistake is that it failed to understand that the US was not following the same path of gentle decline as Europe,” says Peter Fuhrman, CEO of China First Capital.

As stories of China’s supposedly predatory lending practices come to the fore, the US is seeing development finance as a key competitive arena. Much of the motivation for creating a new $60bn US development bank – currently awaiting a Senate vote before likely ratification later in 2018 – is motivated by a desire to counter China’s growing global influence. Economic diplomacy, in other words, is coming back to the fore as a way to increase political power.

Sri Lankan fallout

Since the beginning of 2018, several countries across Asia have expressed displeasure at the terms of projects they have undertaken with China. Many of these fall under the aegis of Mr Xi’s Belt and Road Initiative, which aims to build a new silk road linking Asia to Europe via a massive programme of infrastructure projects.

First there was the Chinese-built port in Sri Lanka that China assumed control of in late 2017. Unable to repay loans on the $1.3bn cost of the Hambantota port, which opened seven years ago and has seen sparse traffic, the Sri Lankan government handed the port to China through a $584m deal with state-owned China Merchants Port Holdings.

China views Hambantota as a key project for the Belt and Road Initiative, one of a planned network of some 60 ports spanning the globe. Critics claimed the move was an erosion of Sri Lankan sovereignty. Western powers including the US and Japan raised concerns that China would use the port as a military base, something the Sri Lankan authorities deny.

Some claim, further, that China deliberately imposed untenable terms on the project. “Beijing typically finds a local partner, makes that local partner accept investment plans that are detrimental to their country in the long term, and then uses the debts to either acquire the project altogether or to acquire political leverage in that country,” Constantino Xavier, a fellow at think tank Carnegie, told the Financial Times at the time of Sri Lanka’s port handover.

Others disagree, blaming incompetence at the Sri Lankan state-owned operator for the project’s failure. “In this case [the Chinese] said: 'Here’s the money, we’ll build it and even a moron running this thing will generate the free cash flow to pay us back.' But they couldn’t or wouldn’t run it. It became this crazy satrapy of government mismanagement and corruption,” says Peter Fuhrman, CEO of China First Capital.

“The Chinese, in that instance, did not structure it so it would fail. The Sri Lankan authorities just could not keep up,” he adds. As a counterpoint he highlights that China also built Sri Lanka’s highly successful port in Colombo several years earlier.

That also came with strings, however. Part of the Colombo port deal gave China sovereignty over more than 20 hectares of land within the port complex, and it has docked naval ships and submarines there, prompting objections from India and Japan.

Anger in Asia

Sri Lanka is not alone in beginning to have doubts over its relationship with China. Malaysia has cancelled three pipeline projects and a rail project linked to the Belt and Road Initiative in the past few months, alleging links between the deals and payments into the 1MDB fund, the former Malaysian state investment fund at the centre of a global corruption scandal.

In the Philippines, firebrand populist president Rodrigo Duterte has lashed out at China several times in 2018. Polls show Mr Duterte’s popularity slipping while concerns about China’s inroads into the country, which the president had encouraged, are growing.

In perhaps the biggest blow to China, Pakistan’s new government intends to review or renegotiate the terms of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor project. With a $62bn price tag, it is one of the most ambitious projects of the Belt and Road Initiative. Pakistan’s finance minister has criticised the lack of transparency around the terms struck with the previous administration, and there are rumours the government also wants to renegotiate the terms of its free-trade agreement with China.

Coupled with China’s escalating trade war with the US, the Far Eastern giant is in an uncomfortable position, according to some. “China looks at its near abroad and doesn’t see a lot of friendly faces,” says Mr Fuhrman. “So where China is with Focac and Belt and Road is: how do I cope, as a rising, aspiring power that has no real allies?”

Not so transparent

Attempts to break down China’s total development finance commitments in different regions of the world run up against several complications. The first is one of categorisation. The nature of China’s liberalised command economy blurs the lines between Western conceptions of aid and loans, and between public and private sources of capital.

A 2011 white paper published by China’s State Council defines aid as “financial resources provided by China for foreign aid mainly fall into three types: grants (aid gratis), interest-free loans and concessional loans. The first two come from China’s state finances, while concessional loans are provided by the Export-Import Bank of China as designated by the Chinese government.”

However, China does not participate in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s (OECD's) Development Assistance Committee standards, the international body that sets standards for and keeps account of aid flows from other donor countries. Disentangling state-backed financing is even more complicated. Export credits, guarantees, co-ventures and project advances are mixed together with grants and policy loans from state-controlled banks.

The other, related, difficulty is one of transparency. Finding accurate numbers on Chinese total debt stock for a country or part of the world, for instance, is all but impossible. Best estimates, published by the SAIS-CARI institute at the Baltimore-based Johns Hopkins University, put total debt stock for Africa for 2016 somewhere in the range of 22%.

“Our current estimate of all Chinese loans committed to African public sector borrowers between 2000 and 2015 is $102bn and our preliminary (still unpublished) estimates for 2000 to 2016 are $132bn,” the researchers say.

Transparency is also an issue when attempting to distinguish between pledged amounts and disbursed investments. Most official numbers from China only deal with pledges, while actual disbursement is difficult to track. In Zimbabwe, for instance, total pledges from China over the past two decades total some $33bn but some sources claim only $2.5bn of that has been released so far.

Lack of transparency about numbers, coupled with China’s willingness to put governance and reform standards to one side, puts it at odds with Western standards for development assistance – and this breeds distrust.

South-south pitch

China’s pitch to other developing countries positions itself as a peer and an equal – in contrast to the edicts issued by Western institutions. If 'win-win' co-operation is the government’s tagline for international engagement, then concepts such as 'the five nos' for its engagement in Africa are the cornerstone of its policy of non-interference.

They are as follows: no interference in the way African countries pursue their development paths according to their national conditions; no interference in a country’s internal affairs; no imposition of China’s will on African countries; no attachment of political strings to assist Africa; and no seeking of selfish political gains in investment and financing co-operation.

“I think when President Xi talks about ‘the five nos’, that’s very genuine. We don’t think we know better, we don’t try to tell them what policies they should follow but would like to share our own experience and lessons. We believe our goodwill in knowledge sharing and investment for development will be validated over time,” says Jiang Xiheng, vice president of the state-backed China Center for International Knowledge on Development.

This pitch has proved appealing to governments in poorer countries who are not favourites of Western donors, and who are tired of being dictated to by the World Bank and OECD countries. And while China’s willingness to deal equally with oppressive or poorly run countries without reprimand makes Western counterparts uncomfortable, advocates of this approach say the results speak for themselves.

“Before we talk about anything else, on the ground there are new roads, there is clean water... this is a very important transformation that China has helped make. Clearly there is an impact,” says Ms Hai.

“Is China going into these places and saying: 'Here, take this debt while we build something?' It doesn’t work like that. There’s a huge infrastructure gap in these countries, and clearly international development agencies like such as World Bank and the IMF haven’t found the perfect solution. They have been trying for 60 years.”

Through the lens of China’s own recent development trajectory, some argue that rather than seeking to control other countries through debt, these countries’ inability to develop and boost growth despite investment has proved baffling to China – mirroring Western soul-searching about the lack of progress seen from its own development investments over several decades.

“China is now running up against limits on Chinese capital. The rest of the world has proven hugely disappointing. The internal rate of return [on infrastructure investment] has not been anywhere near China’s levels, and this is where they have bitten on debt accumulation,” says Mr Fuhrman.