Home or Away: where will China get its gas?

Gas-producing and gas-hungry countries the world over are keenly watching what happens in China as it continues to negotiate with various suppliers over the price of its natural gas imports while examining the possibility of developing its unconventional gas reserves.

The latest data from China’s National Development and Reform Commission shows a huge rise in gas imports. From January to August 2011, imports had nearly doubled over the same period in 2010. Gas imports for August hit a new record of 3.4 billion cubic metres (bcm). For the first eight months of this year they reached a total of 20.2bcm. The increase is no surprise, given that China’s gas consumption saw a compound annual growth rate of almost 16% between 2000 and 2010, and shows no signs of slowing.

The demand for imports is fuelled partly by China’s goal of making gas 10% of its energy matrix by 2020, largely to reduce coal consumption. Currently, while gas accounts for only 4%, that still makes China the world’s fourth largest consumer of gas.

Editor's choice

Meanwhile, domestic production was only 95bcm in 2010, and PetroChina is aiming to increase this to 150bcm by 2015. Importing gas is an expensive option compared with developing domestic sources, but demand is growing so fast that there is no other option.

“With consumption growth outpacing that of production, China has become a net gas importer since 2007 and, therefore, subject to the regional Asian gas price, which is indexed to oil,” says Thierry Bros, senior analyst in the cross-asset research team at Société Générale.

In the pipeline

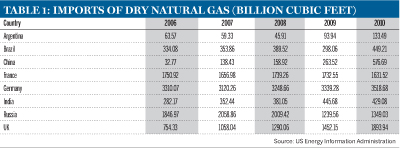

China is increasingly reliant on imports of both dry natural gas (see table 1) and liquefied natural gas (LNG). Half of its imports come through a pipeline from central Asia. Agreements with the countries along the route of the pipeline – Turkmenistan, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan – to input more gas are part of a long-term energy security plan. The 2000-kilometre pipeline opened in 2009 is expected to achieve an annual capacity of 30bcm in 2012, and the China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) has plans for more pipelines to central Asia.

The rest of China’s imports are in the form of LNG shipments from countries such as Indonesia, Qatar, Malaysia and Australia. This year, a new LNG terminal – China’s fifth – opened in Dalian. Operator PetroChina expects the first shipments to arrive before the end of the year.

Clearly, there is major investment in all elements of gas production and infrastructure. New import pipelines and LNG terminals are just part of the story. Construction of the second component of the west-east pipeline, which carries gas through China, is under way.

“There are ambitious plans for domestic production growth and six more LNG terminals are planned by 2015 with most of the capacity already contracted on long-term contracts. From nothing a couple of years ago, the pipeline from Turkmenistan should bring in 17bcm this year. But if consumption rises as hoped then there may be some shortfall in 2015,” says Deutsche Bank’s lead gas analyst Michael Hsueh.

Russian solution

The possibility of a long-term shortfall in gas means China is constantly looking for new opportunities to secure energy supplies. In October, Russia’s prime minister Vladimir Putin was optimistic about concluding a $1000bn natural gas supply agreement with China that has been under discussion since 2006. Though parties are said to be working hard on finalising the deal, it remains stalled over the price. Mr Putin’s meeting with Chinese premier Wen Jiabao in October did not yield any conclusion to the deal, so talks will continue at their next meeting in November.

“Russia wants to sell gas to China and China wants to buy gas from Russia, but the agreement is held up by differences on price. It is a difficult negotiation between two very powerful players,” says Trevor Sikorski, head of environmental markets research at Barclays Capital.

Russia is seeking prices similar to those it receives from western Europe, while China is looking for prices comparable to imports from Turkmenistan. If it pays more to Russia, that could trigger discussions about paying higher prices for gas from central Asia. “China can afford to look for good terms with Russia, but both sides are holding their ground on price,” says Mr Hsueh.

Shale resources

The relative importance of any deal with Russia may depend heavily on how well China can exploit its own reserves of unconventional gas – coal-bed methane and shale gas – in the years ahead. Technological advances have made these reserves increasingly viable, which has had a staggering effect on the US market.

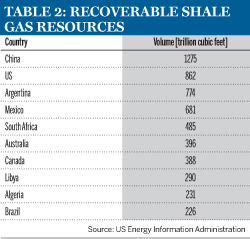

Some estimates put China’s shale gas reserves at 36,000bcm (or 1275 trillion cubic feet, see table 2). This represents the largest reserves in the world, outstripping the US, where shale gas has turned the gas market on its head by dramatically increasing total gas output and sending prices tumbling over the past five years.

This example has not gone unnoticed, hence the efforts by policy-makers and state energy companies in China to lay firm foundations for shale gas extraction, although nothing has been produced to date. The Economist Intelligence Unit estimates that China’s shale gas reserves could be 12 times greater than its reserves of conventional gas.

By developing shale gas, China could both reduce its dependence on imports and minimise the use of coal, which are key goals of its long-term energy policy. The five-year plan ending in 2015 prioritises the development of shale gas and the first block tenders took place this year.

“Future growth will mainly come from unconventional gas. Our technology and experience still lags behind Western oil companies, but we don’t have to wait until our technologies mature. We can hire them to work for us,” says Fu Chengyu, chairman of Sinopec.

Outside help

China’s energy companies are showing they are keen to work with foreign partners. PetroChina and Royal Dutch Shell are exploring in the Sichuan Basin in south-western China. BP, Chevron and Statoil are among the companies reported to be keen to play a role in future developments. An agreement with the US to measure shale gas reserves and encourage both joint investment and technical co-operation in future production.

“European IOCs [international oil companies], which missed the US shale gas revolution and have little hope of using fracturing in Europe, would be more than happy to participate in China. So far, Shell, Total and ENI have reported unconventional deals in China. China has the resources, the engineers and the manpower. IOCs and service companies could provide the technologies and the rigs to fast-track the process of unlocking these extensive resources. If China manages to replicate the US success story, we could continue to see the gas global market well supplied until 2020,” says SG’s Mr Bros.

The political and commercial momentum behind unconventional gas development in China should not be underestimated, though it will be a tough task.

“China’s conventional reserves are not big, but the wild card in all this is unconventional gas. China’s reserves look good in both coal-bed methane and shale gas and it is looking to develop both. The goal is to produce 20bcm of methane by 2015, but it is not easy to extract. For shale gas, the targets are 5bcm by 2015 and up to 30bcm by 2020, but there are issues with challenging geographies,” says Mr Sikorski.

In the US, shale gas is found in flat plains, but in China it is often in more mountainous areas. “[This requires] a lot of water to get the gas out, so it is very challenging. But any domestic gas supply is cheaper and more secure than imports, and it is cleaner than coal, so unconventional gas hits a lot of the right buttons in China,” adds Mr Sikorski.

Delicate balance

Whether China’s spiralling demand for gas shifts the balance of the global market, to the detriment of other large gas importers, remains to be seen. There are currently too many unknown variables – not least unconventional gas – to build a definitive picture.

“In the long run it depends on China’s ability to bring on unconventional sources of gas. But there are widely varying estimates on the amount of shale gas in China. Some say its reserves are very large and could be available at $6 to $9 per million btu [British thermal units], but there are a lot of unknowns and there needs to be a lot more exploration,” says Mr Hsueh.

There would certainly be cause for concern if China’s LNG imports inexorably rise at their current pace. Figures from China’s General Administration of Customs state a 17% year-on-year rise in September’s LNG imports, and at significantly higher prices. A tighter market puts more pressure on spot cargoes and higher prices erode the proposition that LNG is a cheaper source of gas.

“In the long term, China could take a lot more cargoes of LNG, which could affect countries that have invested a lot in regasification facilities [where liquefied natural gas is returned to its initial, gaseous state]. That could be an issue for the UK, which has become more reliant on LNG, so the market is very sensitive to any news that LNG is going elsewhere. This is exacerbated by the growing investment in regasification facilities in the Middle East and Latin America, hence the UK’s enthusiasm to develop shale gas,” says Mr Sikorski.