Structured products go sustainable but framework needed

The success of green bonds has spawned a demand for sustainable structured products, but if this youthful market is to succeed it will require a formal framework, say participants. Danielle Myles reports.

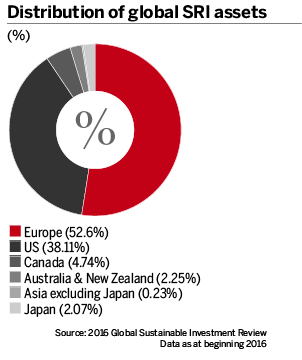

Ten years after the debut transaction, green bonds are on the verge of becoming the first socially responsible investing (SRI) asset class to hit the mainstream. The success of the $700bn global market is attributable to a multitude of factors.

More from this report

Chief among them is corporate social responsibility, which has worked its way up issuers’ agendas, and the buy-side giving more weight to environmental, social and governance (ESG) criteria in investment decisions. The latter has also realised that climate change potentially damages the value of their long-term investments.

Naturally, market participants are now searching for the next incarnation of SRI instruments, which has led to the development of many new structures including green securitisation, forest bonds and, most recently, sustainable structured products.

Bringing ESG to retail

As with most new asset classes, multilateral institutions are among the inaugural issuers of these structured notes. In 2014 the World Bank privately placed green notes for which the return was linked to the Ethical Europe Equity Index. The following year, the European Investment Bank (EIB) launched a product called Tera Neva, consisting of a climate awareness bond with a payoff linked to a climate-aligned index.

However, some investment banks are also leveraging off their structured product franchises to offer similar instruments. Some US lenders have shown an interest, but French banks have been the most prevalent issuers to date.

This new breed of structured products is changing the composition of the ESG investor universe. Neven Graillat, head of sustainable investment solutions at BNP Paribas, says sustainable investment’s acceptance as "the new normal" has been driven mainly by asset owners and institutional investors, but there is more traction among individuals and retail, from whom he expects to see only more inflows.

It is a claim supported by Eurosif’s latest European SRI Study, which shows that at the end of 2015 retail held 22% of ESG assets globally compared with just 3.2% at the end of 2013. “[That’s] mainly driven by the fact that investment banks are now able to offer structured solutions that combine the financial characteristics needed by these clients, with the rapidly developing ESG criteria,” says Isabelle Millat, head of sustainable investment solutions at Société Générale Corporate & Investment Banking (SG CIB).

Indeed, the bank has responded to a rise in retail demand by combining its structured product platform, distribution network, ESG credentials and ESG in-house research capabilities to become an early leader in this nascent market.

Some multilaterals’ deals offer further proof that structured products can expand the ESG investor base. The World Bank’s equity-linked Green Growth Bond programme, for instance, has been sold in every major region and to the full spectrum of investors including retail, private bankers, pension funds, insurance companies and high net worth (HNW).

“Green bonds are more for institutional clients, who have portfolio management needs. But when it comes to reaching individuals, wealth managers and HNW, I think adding this equity-linked feature is the key to its success,” says Mr Graillat of BNP Paribas, which designed the programme.

Investor rationale

Nevertheless, institutional investors that adopt ESG criteria are still drawn to these structured products, and for good reason. As one banker notes, they are looking for the magic triangle of ESG impact, liquidity and yield. In a low-interest-rate environment, the yield pick-up offered by a structured pay-off makes these instruments particularly attractive, as does the possibility of more bespoke financial characteristics.

“If you are facing an investor who wants something more customised – for instance, some level of capital guarantee or protection, or a customised maturity – then they will need a structured product,” says Ms Millat. “They can’t get that with a vanilla green bond.”

Aviva France is a good example of the type of institutional investor moving into these products. It invested in the EIB’s Tera Neva transaction back in 2015, and has been won over by the multiple benefits offered by sustainable structured products.

“The key attractions are the ability to adjust the risk-return profile, by selecting the underlying we want to be exposed to, and the fact it clearly fits with our responsible investment strategy to take into account environmental impact and climate change risk,” says chief investment officer Philippe Taffin.

Following Tera Neva, Aviva France will look to invest in other structured green products. As Mr Taffin notes, adding ESG criteria into its mix of structured products – which it has purchased since 2012 – is not a big leap. “We have been doing this for many years so applying the same sophisticated technology, but using a green note, is pretty straightforward for us,” he says. “Structured green bonds are just a natural follow-on from what already exists in the market.”

Customisation is king

A defining feature of the sustainable structured products market is that it has sprung up to satisfy buy-side firms chasing the magic ESG triangle of yield, liquidity and impact.

“The ultimate driver is the investor side,” says Vinay Samani, a partner at law firm Linklaters. “But we have received queries from banks which, I suspect, see the ethical investors base as a new target audience for structured products.” It means issuers must be able to offer true customisation to remain competitive.

First, they must be able to adapt to the different ESG investment strategies and styles emerging around the world. In Europe, for example, investors typically engage in negative screening to exclude any controversial sectors from dedicated funds. In the US, however, they prefer a process known as ESG integration, whereby they add some ESG criteria across each of their funds.

“Each investor has their own approach to ESG and this is where the customisation abilities of a bank such as Société Générale are very relevant,” says Ms Millat. “We can adapt to any client in any country.”

Second, issuers must be able to tailor the underlying, to cater to the investor’s particular needs. The most common underlying so far has been indices. There has been a huge increase in the number of ESG-themed indices created by banks and specialist index providers in recent years. Banks such as SG CIB, which have a well-established index franchise, have an advantage as they can create a bespoke index for a client, rather than just pushing their flagship products.

Other possible underlyings include a static basket of equities, chosen to align with the investor’s particular ESG priorities. An alternative is ESG-compliant funds. This is particularly relevant in France, where the government has created an official SRI label for qualifying funds. Since its launch in early 2016, about 70 funds have received the accreditation, creating a new form of underlying for sustainable structured products.

Positive impact structured notes

One of the most promising developments is a category of instruments known as positive impact structured notes (PISN). Pioneered by SG CIB, PISNs can make use of the full range of underlyings used in conventional structured products.

What sets them apart is that for the life of the investment product, SG CIB commits to provide positive impact projects with funding that equals (or exceeds) the PISN principal. For example, if a client invested €5m in a PISN with a maturity of five years, SG CIB commits to hold on its books €5m of positive environmental or social impact assets for five years.

The idea dates back to 2012 when SG CIB started to review its portfolio of projects to identify those that had a positive environmental or social impact. Since then, the bank’s pool of PISN-eligible projects has continued to grow; in 2016 its positive impact finance transactions amounted to €2.23bn, up from €1.9bn the year before.

Investor appetite for PISNs is also rising. “Success so far has been mostly with distribution networks in France and Italy, but they’ve also gained traction with third-tier institutional clients in Benelux, and also some in the UK,” says Ms Millat.

They have been particularly popular with the likes of universities and foundations as the note can be structured to offer the financial characteristics these institutions need (such as a capital guarantee), and the principal is invested in causes that align with their values.

Use of proceeds

The nascent market for sustainable structured products is struggling with some of the same issues that faced the green bond market in its formative years. The biggest is a lack of clear definitions – there is still no consensus on what qualifies as a sustainable structured product. Some market participants say a structured product where the underlying is ESG-compliant will qualify. Others believe use of proceeds is the key criteria, while many believe both the pay-off and principal should satisfy ESG criteria.

Sean Kidney, CEO of the Climate Bonds Initiative, is adamant that for any instrument to be classified ‘green’, the funds must be used accordingly. He takes issue with some purportedly green structured products issued by a multilateral from which a sizeable portion of the principal was allocated to general treasury functions. “What counts is the use of the proceeds,” he says. “They must go to substantive projects.”

Investors are making similar demands. Within their magic ESG triangle, they are increasingly focused on impact. They want their funds channelled into worthy – and, if necessary, riskier projects – plus full transparency on the projects’ identity and performance.

It’s an area in which SG CIB’s PISNs cannot be faulted. The framework for identifying and managing PISN-eligible assets is fully aligned with UN Environment Programme Finance Initiative’s Principles for Positive Impact Finance, which provides a common methodology for financing the UN’s 17 Sustainable Development Goals.

“It is a very stringent, in-depth assessment where you not only ensure the project has a positive impact on one of the three pillars of sustainable development, but also that any potential negative impact is identified and managed,” says Ms Millat. For instance, if the funds are assigned to building a renewable energy plant, it must not create noise pollution.

If they go towards public transport projects, the sponsors and even sub-contractors must also abide by the principles. Furthermore, for the life of the PISN, investors receive annual reports from SG CIB – including a third-party opinion – on the positive impact finance quality of the underlying projects.

A common framework

In the footsteps of the Green Bond Principles, market participants are calling for industry-wide standards to help the sustainable structured product market mature. Clearer definitions and formal guidelines would create more consensus and may pave the way for a more tangible asset class.

“I almost see it like Islamic-compliant bonds,” says Linklaters’ Mr Samani. “If there can be some official, independent accreditation that deems the bonds compliant, there is the prospect of a bigger market for the products. It would increase investor appetite.”

A number of bodies could take the lead on this. The European Commission recently set up a high-level expert group on sustainable finance, which is due to issue its first set of recommendations in 2018. BNP Paribas’s Mr Graillat says the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals could provide a fantastic umbrella for such a framework, and that it is already proving a useful reference point. “In the past when you talked about [sustainable development] with clients you each had different views,” he says. “Now with this common framework, it’s normative, and more people are looking at getting involved.”

Investors agree the principles have provided a useful common vocabulary, but they still want more formal guidelines. “The [UN] goals are quite clear, and we strongly support them, but both we and issuers need a firmer framework,” says Aviva France’s Mr Taffin.

Specifically, investors want more concrete reporting requirements such that the transparency offered by top structured product houses – notably an independent ESG auditor, full disclosure of the project’s credentials and updates throughout the investment period – become market standard. Some are even calling for transparency on the project’s performance after their structured note has matured.

A matter of education

Bankers have reason to be bullish on sustainable structured products’ growth. Retail is taking a bigger stake of the ESG investment universe, and lawyers report a bigger pick-up in bank queries regarding sustainable structured notes than sustainable securitisation. Undoubtedly, guidelines will help take this asset class to the next level.

But Ms Millat also stresses the importance of innovation regarding underlyings, and educating advisers and distributors – including on the fact that investment and ESG criteria can co-exist. “It’s our responsibility to make sure that these intermediaries are fully aware of what these products are, why they perform and what they do well,” she says.

Sustainable structured products may not reach the scale of the green bond market – from which analysts expect up to $150bn issuance this year alone – but they are proving an invaluable way to connect a broader range of investors to ESG-aligned projects.

Mr Kidney and the Climate Bonds Initiative may be prioritising vanilla products, on the grounds they can mobilise more funds into green assets, but he is willing to fight the battle on all fronts, and agrees there is a place for green structured products. “The climate change situation globally is in such a bad way that we have to try everything,” he says.