Yield-starved investors turn to structured products

Record low interest rates and quantitative easing is prompting bond buyers to seek alternative ways to gain credit exposure, with derivatives gaining traction as a good proxy. Danielle Myles explains why.

Ask institutional investors what their biggest headache is, and the response is unanimous. The hunt for yield has been all-consuming for a few years now, with more than 20 central banks having slashed interest rates to zero or into negative territory to kick-start their flagging economies. But the decision by the European Central Bank (ECB) to radically extend its quantitative easing (QE) programme to include up to 70% of eligible corporate bond issuances has created a new sense of desperation.

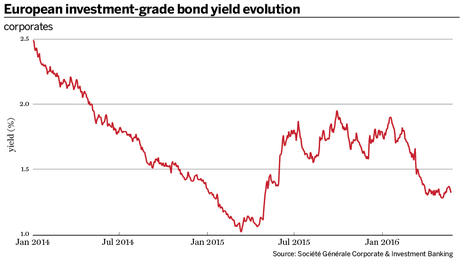

Leading up to its implementation earlier in the year, blue-chip borrowers from both within and outside the eurozone seized the opportunity to raise large volumes of cheap, euro-denominated debt. However, for pension funds, insurers and other buy-side firms that have promised – and have grown accustomed to achieving – circa 5% returns for their clients from traditional, long-only portfolios in the highest rated names, it is proving an abrupt wake-up call. European investment-grade corporate bonds are yielding on average a dismal 1.3% (see chart), meaning a shift in mentality is needed.

“From clients I speak to, and their end clients, people are not able to adjust to the idea of the risk-free rate being so low or even negative,” says Mike Riddell, a fund manager at Allianz Global Investors. “Anyone who has committed to paying out a certain interest rate over the next five, 10 or 20 years is in deep trouble.”

More from this report

Some investors have responded by diversifying into emerging market names, ultra-long-dated government bonds and exchange-traded funds. A growing number, however, see the merits of credit derivatives – namely yield, liquidity and the ability to conduct smaller trades – as a better option to adding to their bond holdings.

Optimising portfolios

Recent advancements in bond repacks have spurred greater interest from European insurance companies, pension funds and some banks. At its simplest, the structure sees the investor sell (often government) bonds off its balance sheet to a bank, which places the bonds into a separate vehicle. The client then invests in a structured note issued by the vehicle, which pays an index-linked return rather than the underlying’s fixed coupon.

The credit risk is the same, but by adding certain features the return can be increased. “Simply holding the bond, they could not achieve the yield they were looking for. So they are happy to add an additional risk to increase the yield of the bond,” says Antoine Broquereau, global head of financial engineering, fixed income, credit and currencies at Société Générale Corporate & Investment Banking (SG CIB). Callability is a simple but effective example of how this is done, and banks active in this space are working with clients to identify other features that meet their needs.

While repacks are spreading across Europe, they have gained the most traction among investors in Belgium, Italy and France looking to optimise their respective governments’ bond holdings. SG CIB has been at the vanguard of repack solutions, and earlier this year it became one of the few derivative houses to create a repack based on an emerging market bond (which tend to be less liquid) that is callable.

“Creating a callable structure based on a Turkish bond was something completely new. We were happy to build such a product for the client and manage the risk over the life of the product, because we are comfortable with the way we could hedge that risk,” says Mr Broquereau.

Refinements to the issuing format have also garnered investor interest. “We saw a gradual shift of model where you were offering a standalone special purpose vehicle set up for a particular transaction, to using a euro medium-term note (EMTN) programme that allowed us to create this kind of structure,” says Mr Broquereau. “The beauty of the EMTN programme is that it is an industry-recognised and cost-efficient method which, when regulated, means your EMTN programme has been approved. This has created an environment for investors that is completely different from what we have seen in the past.”

Only a handful of other banks are using their EMTN programmes in this way, including Deutsche Bank, Credit Suisse and Japanese banks that play a key role in the domestic repack market. The cost, technology and required operational expertise has, says Mr Broquereau, created some barriers to entry. “It doesn’t mean we don’t have competition, and we are happy to get competition as that’s the way to serve our clients best. But we are still looking at adding new features and to structure even more efficiently in terms of client expense so that we remain, at least for a period of time, ahead of our competitors,” he adds.

Tranching iTraxx

While repacks are helping investors better utilise their low-yielding holdings, the past year has seen a broader range of players invest in credit index-linked products as an alternative to piling into more bonds. According to Depository Trust and Clearing Corporation statistics, trading volumes on iTraxx indices, based on a basket of credit default swaps (CDS), have surged in recent months.

Low yields may dominate the headlines, but they are not the buy-side’s only battle. “The liquidity picture is also not that great, which is a function of regulation and central bank policy. Bonds are suffering a real confidence issue right now,” says Salman Ahmed, chief investment strategist at Lombard Odier Investment Managers.

A growing number of investors are becoming accustomed to the liquidity associated with iTraxx, and the extra boost it has received recently from bank counterparties needing to cover their own exposures. “Products linked to credit indices are becoming more popular for one specific reason: the emergence of counterparty valuation adjustment desks in the banks has created more need to hedge the credit risk of derivative portfolios, and hence more liquidity on the indices,” says Mr Broquereau.

Among high-net-worth (HNW) investors there is a strong trend towards tranche products – particularly those linked to the iTraxx Crossover Index, which reflects European high-yield CDS. Tranches create exposure that correlates to a tier of the capital structure – be it equity, mezzanine, super senior – creating the possibility for greater leverage, and greater yield.

But while investors are keen, the number of banks willing to create tranches has diminished as regulatory reforms have made the activity more capital intensive. SG CIB’s strategy is a type of economies – or rather, diversity – of scale; a broader mix of clients brings down capital costs through the likes of netting. “If you want to be a player, you have to have a diversified business. You need clients that are long-term institutions, hedge funds, asset managers, HNW individuals; you need to be able to get a mix that makes sense to carry out this business,” says Mr Broquereau.

Outside the box

Repacks and iTraxx tranches are just two ways European investors are using credit derivatives as a proxy for lacklustre bond returns. HNW investors are also taking single-name risk, while others are asking banks to create products that index CDS baskets tied to certain sectors or credit ratings. Structured credit strategies, however, are not for everyone. Mr Riddell, for example, says they are not suitable for mutual funds, but he does see the strategy’s merits. “For very long-term buy and hold investors, pension funds or the big institutional investors, I can see how it makes sense,” he says.

The move to structured credit is indicative of a broader trend of investors being forced to stray from their traditional asset classes of choice. SG CIB’s global head of engineering, Marc Saffon, observes other strategies used by insurers (and some banks) to monetise their holdings in addition to bond repacks. “We see more and more demand from investors trying to sell volatility on their large books of government bonds. Essentially they are selling short-dated puts, betting that the yield will not go up,” he says.

Given the ECB says low rates will outlive any form of QE, it seems a sensible strategy. It also makes it difficult to create value within any single asset class, which creates more appetite for holistic investment solutions. “The more government bonds go into negative rate territory, the more investors realise that to generate yield like two or three years ago, you need to either take more risk or diversify into asset classes and be nimble about those you go into,” says Mr Saffon. “Not all of them have made the jump to cross-asset solutions yet, but that is definitely the trend.”

While the move to structured credit is perhaps most pronounced in Europe, a similar phenomenon is occurring in Asian markets living with unconventional monetary policies. In Japan, which has been dealing with Abenomics for about three years now, bond repacks and even single-name credit-linked notes are incredibly popular. And while Taiwan and South Korea's policy rates have not yet hit zero, they have dropped rapidly. This, according to Mr Broquereau, can be as much a catalyst as the absolute level of rates. “[It has] forced investors to look at their portfolio and react fairly quickly,” he says.

The macroeconomic uncertainties plaguing Europe make it difficult to assess whether structured credit will become a permanent alternative to bond buying, or whether another proxy will appear on the horizon. “This is new to everyone, so I think what we are seeing to some extent is investors’ immediate reaction being to look to an asset class that they know well. They understand credit, so it’s quite easy for them to move into it,” says Mr Broquereau. “But we can’t live in a negative yield environment forever, and in terms of what happens next, I have no clue.”

In the meantime, derivative houses are ready and willing to help investors find the yield they desperately crave.