Financial services have undergone a deep transformation in the last few years, one such change being the rise of banking-as-a-service – or BaaS – which was particularly prominent in Europe in 2022. By Laura Grassi of the Fintech & Insurtech Observatory.

Last year was certainly very unusual for the financial and insurance sector. A turbulent geopolitical situation, burgeoning inflation and the jump in interest rates introduced by central banks worldwide together rapidly changed the financial landscape.

Innovation, however, did not grind to a stop. In 2022, Politecnico di Milano’s Fintech & Insurtech Observatory surveyed 1392 fintech start-ups based in Europe (81% up on 2020), finding that they raised $35bn in total over the past five years (73% up on 2020) – an average of $25m each.

Looking more closely at these start-ups, which act as a mirror to European financial innovation, the UK holds its place as the birthplace of fintech in the old continent and is home to 38% of all fintech start-ups, followed by France (11%) and Germany (9%). The sums raised follow a similar pattern: the UK is out in front with $17.4bn, well ahead of France and Germany in second and third place ($3.2bn and $3bn, respectively).

Many of the innovative ideas taking shape are only apparently in conflict. On the one hand, the payments sector is in the lead in terms of the number of unicorns in Europe, having raised $12.3bn, with 29% of fintech start-ups operating in this field. In addition, incumbents have also entered the fray (arguably with good reason, as several big techs have created and are seriously pushing their own payments systems).

On the other hand, digital solutions for managing investments (29% of the start-ups surveyed), crypto assets (23%), lending (17%), insurtech (13%) and regtech (10%) boast – on average – higher margins, are trusted more by end consumers and the required investment in infrastructure is often more gradual. These are, in any case, fields where innovation has yet to reach its full potential.

The benefit of collaboration

It is worth mentioning that roughly a quarter of the 1392 start-ups surveyed do not serve retail or small businesses. Their customers are the incumbent financial, bank and insurance players, a fact that underscores how collaboration with start-ups is already at the core of some of the incumbents’ innovation strategies.

The benefits of an open approach geared towards collaboration go beyond innovation in financial services and faster time-to-market, and even address business process efficiency.

In terms of architecture, collaboration can take many forms, from traditional revenue-sharing models to the more recent open application programming interface (API) models. APIs play a central role in enabling new banking-as-a-service (BaaS) models, the adoption of which gained momentum in 2022.

BaaS makes it possible for any company, digital business or start-up, even those outside the financial world, to deal in banking services. So where is the novelty? In the past, and still today, financial services could only be offered by institutions duly approved by a country’s financial authorities (such as banks). BaaS can extend banking services outside traditional banks, so that even non-authorised operators are able to offer financial solutions.

And there is no skirting around the law. A non-financial player’s offering must always be backed by a player authorised to make that specific proposal, which, besides its services, crucially offers up its licence and its “books”.

BaaS thus opens up new landscapes. On the one hand is the possibility that financial services could be offered by all and sundry. Think of telecoms or utility companies, and above all think of the big techs, which are currently happily ensconced in the paid-for services sector. With BaaS, they would be able to fall back on third-party licences and gain a greater footing in the financial world than today. With this in mind, we must keep a close eye on them.

On the other hand is the fact that relationships with end users and the user experience will go through non-typical financial actors.

BaaS and embedded finance

And this is not all. When a financial intermediary’s product is directly integrated into the customer journey of a non-financial actor and distributed through its channels, we call it ‘embedded finance’. Typical cases could be when a customer asks to borrow funds when purchasing a product online, or takes out travel insurance when buying a holiday.

As the Fintech & Insurtech Observatory data show, this is a particularly likely situation. In Italy, 45% of consumers would seriously consider taking out travel insurance when purchasing a holiday, and a hefty 65% would at least check out an ‘embedded insurance’ offer.

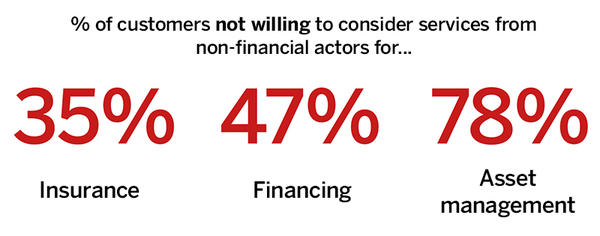

Very few, at least for now, would actually consider embedded offers from non-financial operators to manage their savings (only 22% would take at least one into consideration), though the idea of ‘embedded lending’ is more common (53% of consumers would consider borrowing in this form at least once).

At any rate, embedded finance should not be confused with BaaS. Apart from embedded finance applications, BaaS is today already applied by and in challenger banks.

Challenger banks are small retail banks set up to meet the banking needs of digitally oriented customers who often only want a few standard functions, such as payment accounts or current accounts, which they handle – sometimes exclusively – on mobile devices. Some do not even have a licence of their own: 56 of the 120 challenger banks operating in Europe are fully BaaS-enabled, so their services are delivered through authorisations held by a partner financial institution.

Potential pitfalls

While BaaS allows digital companies without a banking licence to offer financial digital services to their customers – including online current accounts, payment solutions, credit cards, loans, insurance and investments – this could be a real headache for the regulator, as licensing one bank could spark off a surge of players offering financial services. Therefore the person on the street (unlikely to be familiar with licence controls) could easily not realise that their “bank” actually has nothing of a bank about it.

Furthermore, in a system heavily reliant on bail-ins, the end user would find it particularly hard to understand what happens should one of the operators in the system go belly up.

Last but not least, BaaS turns a banking licence into a veritable bank asset, one that can be exploited in new strategies both to increase revenue and to reduce costs. Importantly, if these strategies are to work for incumbent banks, they must always be backed by a mindset open to external collaboration and cutting-edge technological infrastructure that enables effective and efficient third-party integration.

Laura Grassi is the director of the Fintech & Insurtech Observatory at the School of Management of Politecnico di Milano. Politecnico’s Claudio Garitta and Filippo Renga contributed to the research mentioned in this article.