Treasurers in the spotlight

With company insolvencies set to hit epidemic proportions in 2009, all eyes are on corporate treasurers to guide their businesses through the turmoil. Writer Charlie Corbett.

Who would be a corporate treasurer in these troubled times? A recent briefing note from the Association of Corporate Treasurers (ACT) on how to plan for the economic downturn advised treasurers, among other things, to “keep your CV up to date and make sure you are better known around the industry”. With company insolvencies set to hit epidemic proportions in 2009, it is a wise piece of advice. As the recession takes hold across the world, the spotlight is shining on corporate treasurers with an unforgiving glare. For it is them, more than anyone else, that are responsible for keeping companies afloat. With the current economic malaise showing no sign of easing any time soon, treasurers are under more pressure than ever before.

The corporate treasurer is a shy, retiring creature, even at the best of economic times, but in a downturn he goes to ground. And this is no run-of-the-mill downturn. Access to credit has become almost non-existent for some companies and the lucky few that are able to renew debt are having to pay a high premium for the privilege.

Relationships with banks are strained to breaking point as hard-up, risk-averse banks pump up fees, while corporate treasurers haggle for better terms.

The first quarter of 2009 will be critical. A recent report from Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer, a law firm, found that in the UK alone, nearly £30bn-worth ($44.2bn) of syndicated bank debt issued by FTSE 350 companies is set to mature this year, with a further £52bn set to mature in 2010 and £47.7bn in 2011.

Refinancing fears

With conditions the way they are, it will be those companies with the biggest debt exposures relative to their earnings that will suffer the most. But what can financial officers do to mitigate this risk? “Treasurers will be looking for markets to stabilise and the banks to start lending again so that they can renew their facilities in 2009/10, but everyone is braced for more bad news” says Stuart Siddall, chief executive of the Association of Corporate Treasurers (ACT). “We need a period of no bad news... before we can breathe a sigh of relief.” All this could take some time, says Mr Siddall, because banks are still withdrawing from some markets and others are repositioning themselves. News towards the end of January that Citigroup was breaking itself up to raise cash, and that Bank of America was forced once again to go cap in hand to the US government to boost its capital, is testament that a consistent period of ‘no bad news’ is still a long way off.

With so much debt that desperately needs to be refinanced, combined with a crippled banking sector, companies are being forced to make sacrifices. “Even corporates with longer debt maturities are willing to give up pre-crunch pricing in exchange for an extension of maturities: higher costs today are being traded for longer-term certainty,” says David Winfield, head of Freshfields’ banking practice.

Market conditions are such that company auditors are scrutinising their financial covenants like never before, looking urgently for ways to de-leverage. “Those that do not have these options can end up asking – and paying – for their covenants to be reset,” says Mr Winfield. “Lots of treasurers had covenant re-sets for Christmas and more will want them [this year].”

Strained relations

Relations between banks and their corporate customers have been transformed. “In many cases, the credit crunch has seen the end of the traditional relationship model between bank and customer,” says Mr Winfield. “Many issuers are now seeing their traditional relationship banks being reluctant to anchor their facilities and are concerned only with reducing their exposures.”

The ACT is conducting a major piece of research on this topic. According to Mr Siddall, the key to surviving such tough times lies in deep relationships. “What we’re seeing is that those corporate treasurers which have developed really strong relationships with the banks, which are multi-dimensional and not just linked to lending and transaction services, withstand the test of the times we live in,” he says.

This is all very well for big name companies, but smaller and more medium-sized companies do not have the luxury of such relations with their banks. Often their only contact with the bank is through borrowing, and that access to credit has dried up.

Despite huge capital injections into the world’s banks and generous government-backed lending guarantees, banks are stubbornly refusing to increase their lending – in particular to small and medium-sized companies. Many in the industry are now calling for yet more capital injections into the banks.

“We shouldn’t just say that a second injection [of capital] is bad news,” says Mr Siddall. “You could view the first injection as one that was related to survival, and if there is another injection, that enables the banks to have the balance sheet and the flexibility to lend again. That doesn’t mean the first injection was a failure.”

Government attempts in the US and Europe to get banks lending again have so far failed to achieve the desired effect, but politically speaking, a second injection of cash will be controversial.

Companies will be forced to seek other sources of financing in 2009. “Corporates will be scouring the market for ways to replace debt that they have been unable to refinance,” says Ken Baird, Freshfields’ head of restructuring and insolvency. “Opportunistic alternative lenders, such as hedge funds and corporate loan funds, may fill some of the equity gap emerging from the banking sector’s reluctance to lend, but at what price?”

Working capital mantra

This route is time-consuming and expensive. In the meantime, companies face the same funding issues. Treasurers across the world are burning the midnight oil searching for other ways to get hold of finance. If they can not access cash through traditional means, the only option left is to scrutinise the internal operations of a firm and squeeze out as much cash as possible. Maximising working capital has become the mantra.

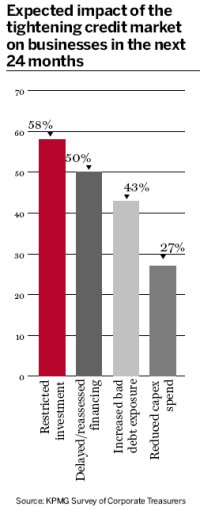

According to a recent survey of 500 chief financial officers across the UK, US and Europe, sponsored by consultant KPMG, cash management was the number one priority for almost a quarter of respondents. The most obvious solution to extracting the most from working capital is in firms negotiating longer payment terms with suppliers on the one hand, and tightening customers’ lines to credit on the other. This might ease the pain temporarily but it is merely a short-term fix, which not only fails to address longer-term funding issues, but can also drive a company’s suppliers into bankruptcy. A bankrupt supplier is the last thing a company needs in such difficult economic conditions. It is essential, therefore, for firms to take a long-term view to maximising working capital, and not just focus on it during a downturn.

Top of the list of priorities should be accurate forecasting. According to a KPMG survey, just 14% of respondents said that their forecasts were on target for the previous 12 months and more than one-quarter admitted that their forecasts were out by more than 30%. Such inaccurate data can lead to businesses having much larger reserve funds than they need and ultimately lower yields because that money could be invested elsewhere.

Linking staff pay to maximising working capital is another often-neglected way of improving cash flows. KPMG’s survey found that the best-performing organisations linked working capital performance to managerial incentives. The reality, however, is that just one quarter of those companies surveyed established a relationship between working capital and pay.

Corporate treasurers face unprecedented challenges. After decades of cheap and easy access to debt, the taps have been turned off. Only those companies that can find ways to squeeze as much cash out of their internal operations as possible are likely to survive the slump unscathed. Being in possession of an updated CV is, of course, good advice, but treasurers would be wise to focus more on improving outdated working capital practices and keep the phone lines open to their relationship banks.