With cash falling out of favour as a result of Covid-19, the global remittances industry has seen a surge in digital transactions, improving the reach of the sector while also lowering costs. John Everington reports.

The surge in the use of digital services has been one of the most noteworthy trends in retail banking during the global coronavirus pandemic. Amid government efforts around the world to halt the spread of the virus by placing restrictions on physical contact, cash has fallen out of favour. Conversely, digital banking services, ranging from contactless payments, opening a bank account and applying for a loan, have seen an explosion of activity, a trend that is likely to continue as lockdowns ease.

Of particular note has been an acceleration of digital transactions within the global remittance industry, notably within payment corridors between developed markets and low- and middle-income countries (LIMCs). In the months since the beginning of the Covid-19 health crisis, both established players and new entrants have reported rises in digital transactions, as cash, the dominant medium within the sector, becomes ever harder to transport in a cost-effective manner.

Such a trend is particularly noteworthy given the sheer scale of the global remittance market, and how the sector’s basic infrastructure often fails those that most rely on it, at a time when the amount of money sent home by migrants is set to fall dramatically in the midst of the coronavirus crisis.

Time for a change

“The global pandemic has exposed the vulnerabilities of the global remittances system,” said Gilbert F Houngbo, president of the UN’s International Fund for Agriculture Development in June, in the run-up to the International Day of Family Remittances on June 16. “That is why now is the time to fix these vulnerabilities, no matter what the economic scenario will be.”

An acceleration of the digitisation of the flow – in tandem with the increased adoption of mobile banking and mobile money services in emerging markets – promises to improve the reach of the global remittances sector, while lowering costs for those benefiting from it.

“The transition from cash to digital has been happening not because people don’t want to handle cash, but because it is significantly more secure, more convenient, and much, much cheaper than doing business via a traditional agent,” says Michael Kent, CEO of money transfer firm Azimo. “I think it’s a one-way street.”

Indeed, restrictions placed on both formal and informal international cash transfers may make the coronavirus crisis a watershed moment for the remittance industry, with traditional money transfer operators (MTOs), banks, telcos and technology firms all playing a part in disrupting the sector via increased digitisation.

Such a process is unlikely to run smoothly however, with hard-to-change customer behaviour and tight regulatory requirements among the challenges that will need to be faced.

Huge numbers

The importance of the global remittance industry, particularly to developing markets, is hard to overstate. Remittance payments to LIMCs grew to a record $554bn in 2019, exceeding both foreign aid and foreign direct investment, according to the World Bank. Such payments support 800 million people in 125 countries, and account for more than 10% of gross domestic product (GDP) in over 30 countries, and more than 25% in countries including Nepal, the Kyrgyz Republic and Tajikistan.

Perhaps surprisingly, remittances to LIMCs are still overwhelmingly cash-based – accounting for 80-85% of transactions, according the World Bank – conducted via established MTOs such as Western Union and MoneyGram, and informal channels such as the centuries-old Hundi and Hawala remittance systems used in the Indian subcontinent and the Middle East and north Africa, respectively.

The impact of the coronavirus is set to trigger the largest year-on-year fall in remittances in recent history in 2020, according to the World Bank, with migrant workers disproportionately impacted by job losses amid a global economic slowdown. Remittances to LMICs are projected to fall by 19.7% to $445bn in 2020, even as the need for such funds grows among remittance recipients.

“Countries such as Nepal, Bangladesh and Pakistan are already showing major declines [in remittance flows] from Saudi Arabia and the UAE,” says Dilip Ratha, head of the World Bank’s Global Knowledge Partnership on Migration and Development.

“We’ve also seen similarly steep declines in flows to Guatamala and El Salvador from the US. For some countries like Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan the fall in remittances [from Russia] could be as high as 27% this year.” A drop off in remittances is likely to have a particularly hard impact on post-conflict nations such as Somalia, Afghanistan and South Sudan, he adds.

Drop in MTO flows

Restrictions on the handling of cash and lockdowns across the developed world has prompted a slump in volumes for MTOs since the start of the crisis in March. For example, Western Union saw a fall in transaction volumes of around 30% year-on-year in the late-March to early-April period, compared with the same period in 2019, according to Brad Windbigler, Western Union’s head of treasury and investor relations. Overall volumes began to stabilise in May as lockdowns lifted, with volumes down by “only” 7% year-on-year.

Yet the company’s digital division has so far bucked the trend throughout the crisis, with growth in transactions coming in ahead of expectations. “Digital was already the primary growth engine for our retail business, growing at around 20% year-on-year,” says Mr Windbigler. “This stepped up to 50% in April and 100% in May.”

Such increases are minute, however, compared to the surge in volumes experienced by digital remittance firms, many of whom experienced their busiest-ever months in March as economies locked down. “The crisis has been a huge driver for our business,” says Mr Kent of Azimo. “We’re well over 200% up on where we expected to be in terms of new customers in the past two months.”

A report by MoneyTransfers.com released in June reported similar record levels of transactions among remittance firms including CurrencyFair, TorFX and Paysend.

The rise in digital transactions has not only come at the expense of the traditional cash businesses of MTOs; while data is hard to come by, informal remittance networks such as hundi and hawala, together with the practice of migrants taking physical cash with them to their home countries when visiting, are also believed to have seen dramatic falls, a result of restrictions on international travel restrictions.

Personal remittances to Pakistan, which account for 8% of its GDP, actually rose by 7.8% between March and June compared with the same period last year, according to the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP). The collapse of informal remittance channels was one of the contributing factors to the increase, according to bankers quoted in the local press, alongside a relaxation of remittances fees by the SBP.

Not over yet

In spite of such trends, it is too early to write off cash remittances, according to Western Union’s Mr Windbigler, with the experience of receiving and using cash still preferred by millions in developing economies despite the increased uptake of digital money and banking services. “I’m not going to disagree with the broad conclusion that the digital uptake is accelerating and will continue at an accelerated rate,” he says.

“But if you think about which side of this equation is more prone to shift [to digital], I would say it’s much more on the sending side," he says. "[On the recipient side] cash may still be more convenient for you, and you may find better deals if you’re using cash. People tend to have established behavioural patterns.”

Ahead of the coronavirus outbreak, around 80% of Western Union’s new digital customers were new to the company, rather than existing Western Union customers. This proportion had not changed since the pandemic, says Mr Windbigler, suggesting the migration to digital among its existing customer base is a gradual process.

The remittance of physical cash remains a favoured option in countries such as Zimbabwe and Lebanon, where official bank exchange rates are significantly lower than black market rates. A Harare-based academic, who asked not to be named, said that Zimbabweans preferred to obtain physical cash via MTOs such as Western Union, MoneyGram and Mukuru and exchange it on the black market, rather than receive remittances in local currencies at greatly unfavourable rates.

Pricing power

The key attraction of digital players such as Azimo and TransferWise over their cash-based counterparts – whether in the midst of a global pandemic or not – remains the price advantage that such firms offer, with even small differences in fees charged making a crucial difference for those that use their services.

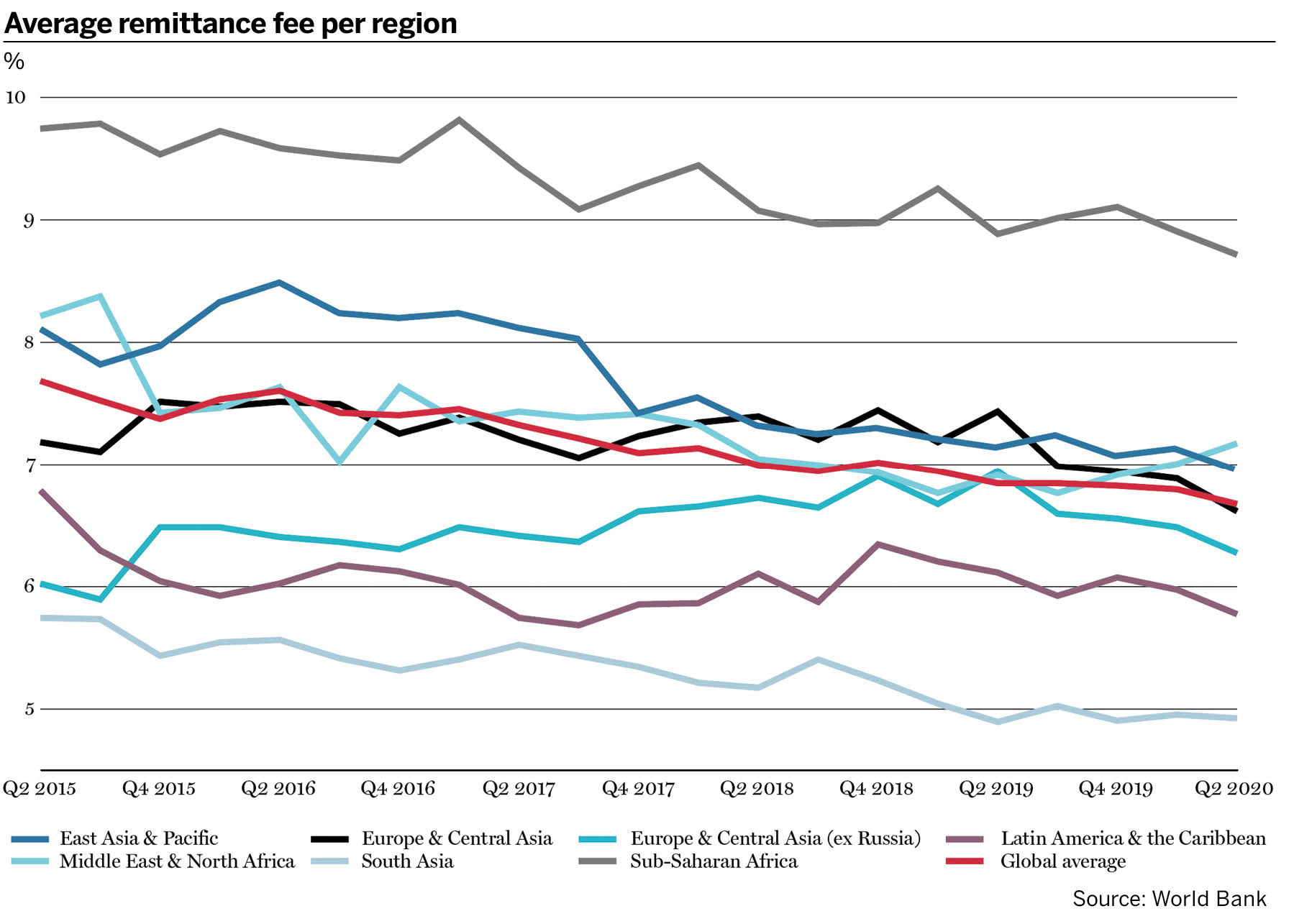

The average global fee for cross-border remittances stood at 6.7% at the end of June, according to World Bank data, down from just under 10% in 2008. On a regional basis, average fees range from 4.92% in south Asia to 8.71% in sub-Saharan Africa.

As part of the Sustainable Development Goal for reducing inequality, the UN has challenged the industry to “reduce to less than 3% the transaction costs of migrant remittances and eliminate remittance corridors with costs higher than 5%” by 2030.

The rise of digital platforms has played a significant role in lowering remittance costs, with further reduction in fees all-but inevitable. “The World Bank statistics highlight a massive and unnecessary inefficiency in the system,” says TransferWise’s CEO and founder, Kristo Käärmann. “I think we’re still only at the very beginning of eradicating costs and making the process much more efficient.”

About $200bn worth of fees is spent per year to remit money within the sector, he says, with a lack of transparency over pricing one of the key factors in why costs are so high. “Most of this $200bn isn’t visible to the people who are paying it; most of that figure represents room for improvement. One of the big ways of improving matters is to inject transparency into the process and how fees are disclosed.”

Mainstream banks remain by far the most expensive option for remitting money according to the World Bank, charging an average fee of 10.57%, compared with an average of just 5.78% charged by MTOs (both digital and cash-based).

“Banks and mainstream financial institutions don’t want to engage with small remittances and prefer to deal with larger customers. This means the poorer you are, the higher the cost of sending money home,” says Mr Ratha of the World Bank.

Rules and regulations

Compliance issues are another thing that keep banks’ remittance costs high, making them reluctant to compete directly on price with MTOs, according to Azimo’s Mr Kent, especially following a series of multi-billion dollar fines levied on lenders such as HSBC, Standard Chartered and UBS for money laundering offences.

“I always say we have to be 10 times better on KYC [know your customer] and AML [anti-money laundering] than we would have to be if we were a bank,” he says. “We have to adhere to the Financial Action Task Force blacklist, and obviously the KYC and AML reporting regulations in the countries that we deal with. So it’s a complicated regulatory stack.”

Complying with such ever-changing regulatory requirements will always contribute to the costs of remittances, according to Western Union’s Mr Windbigler. “It’s not free to understand that kind of risk that’s moving across our network to be able to stop rogue actors,” he says.

While banks may often be reluctant to directly compete with MTOs on lower cost transfers, the deeper penetration of digital remittances is heavily dependent on recipients in developing countries having bank accounts, enabling them to receive transfers into digital wallets. “Bank accounts or credit cards are a must for online remittance transactions,” says Mr Ratha. “There is no quick solution – you have to improve financial access.”

Factors such as the rise of mobile banking solutions worldwide have seen a significant rise in this financial access over the past 10 years; the World Bank estimates that 69% of the world’s adults were banked in 2017, up from just 51% in 2011.

Both governments and MTOs themselves are devising new schemes to enable greater access to banking and remittance schemes for both migrants and receivers of remittances in developing markets.

In February, Seattle-based Remitly announced the launch of Passbook, giving US-based migrants options to open and use bank accounts with fewer document requirements than mainstream banks. Remitly is looking to rollout the service across its wider footprint over time.

Digital identity

Key to the further spread of financial inclusion in LIMCs is the development of robust national identity schemes, which can enable people with little to no documentation to open bank accounts more simply.

The presence of a robust national identity scheme in Kenya, for example, was a key factor behind the success of mPesa, the world’s most celebrated mobile money scheme, which can be used for remittances across its east African footprint, in partnership with MTOs including MoneyGram, WorldRemit and Remitly.

While remittances using mobile money platforms represent a tiny proportion of global remittances, they are by far the cheapest to process, according to the World Bank, charging an average fee of just 3.23%.

India’s Aadhaar cloud-based digital identity system, rolled out in the early 2010s, has greatly simplified the process for opening a bank account, leading to the financial inclusion of millions of Indians for the first time. Meanwhile, the Kiva Protocol, a blockchain-based partnership between the government of Sierra Leone and US-based microloans company, Kiva Project, links a person’s thumbprint with their identity, enabling the easier opening of accounts for the country’s largely unbanked population.