The case for cash is being eroded by innovations in payments and wholly digital business models, yet physical banknotes and coins persist. Is there a future for physical monetary exchange? Joy Macknight investigates.

A “tipping point” has been reached in the journey to a cashless society, according to Philip Lowe, governor of the Reserve Bank of Australia, in a speech at the 2018 Australian Payment Summit in November. “It is now easier than it has been to conceive of a world in which banknotes are used for relatively few payments; that cash becomes a niche payment instrument,” he said. Yet while many argue that a cashless society is ‘inevitable’, letting go of cash is proving hard to do.

Undeniably, the shift to electronic payments (e-payments) is accelerating across the globe. According to the World Payments Report 2018, non-cash transaction volumes grew by 10.1% in 2016, to reach a total of 482.6 billion. Developing markets have seen the highest growth rates, for example India (33.2%), China (25.8%) and South Africa (15.1%). Non-cash transactions are expected to continue to grow at a compound annual growth rate of 12.7% globally, with emerging markets growing at 21.6% from 2016 to 2021. This trend is “fuelled by governments’ efforts to increase financial inclusion and the adoption of mobile payments”, according to the report.

Card payments surge

The most recent Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures’ (CPMI’s) Red Book statistics paint a similar picture. The value of credit and debit card payments as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) has increased by more than one-third across CPMI members over the past decade and, in 2017, amounted to 24% of GDP for these jurisdictions. In addition, card payments are being used for ever smaller payments: the average card payment fell from $69 in 2007 to $48 in 2017. The explosion in online shopping and e-commerce is a main contributor to the shift to e-payments.

Instant payments are also facilitating the move away from physical banknotes, as it replicates one of cash’s main attributes: immediate and final settlement. In his speech, Mr Lowe mentioned Australia’s New Payments Platform, which allows people to make real-time person-to-person (P2P) payments 24/7 using a simple identifier, such as a mobile phone number or an e-mail address. Other real-time P2P initiatives include Zelle in the US, Swish in Sweden and Jiffy in Italy, with many schemes expanding into person-to-business payments.

There are numerous benefits that businesses can gain from moving to an electronic means of payment. A June 2018 Better Than Cash Alliance (BTCA) report, 'The future of supply chains: why companies are digitising payments', lists several positive aspects for shifting away from handling physical cash: greater efficiency and higher productivity; increased revenues and lower costs; greater transparency and security; and stronger business relationships that drive more economic opportunity.

Human behaviour

But is society ready to go cashless? Chad West, chief marketing officer at Revolut, believes so; the digital bank’s chief technology officer, Vlad Yatsenko, has predicted it will happen by 2030. Mr West says: “More of the things we do in our daily lives are connected to our mobile phones. But it is a generational thing – younger people are fully embracing a digital, cashless society, while older generations are not, which is why we predict 2030.”

There is a diminishing association to cash even in mature economies, which are generally seen to be behind emerging economies in moving towards cashless. For example, about one in five people in Europe said they rarely carry notes and coins, and about half indicated they felt they could manage for at least a week without physical cash, according to ING’s International Survey Mobile Banking 2017. About one-third of respondents said that, if it were up to them, they would go completely cashless.

Similarly, a recent Bank of America (BofA) survey found that one-third of Americans say that they could forego physical currency for a week and just over half (58%) believe an entirely cashless society will happen within their lifetime, despite cash and cheques remaining popular payment instruments.

“We think a ‘cashless’ society is possible – and ultimately probable – but it will take some time to evolve behaviours,” says Mark Monaco, head of enterprise payments at BofA. “From a BofA payments perspective, one of our core strategies is reducing the utilisation of cash and cheques through driving adoption of digital payments. We think a digital payment is better, safer and more convenient for our clients. At the same time, removing cash and cheques from the system enables the bank to simplify its operations and reduce cost.”

Cash still in demand

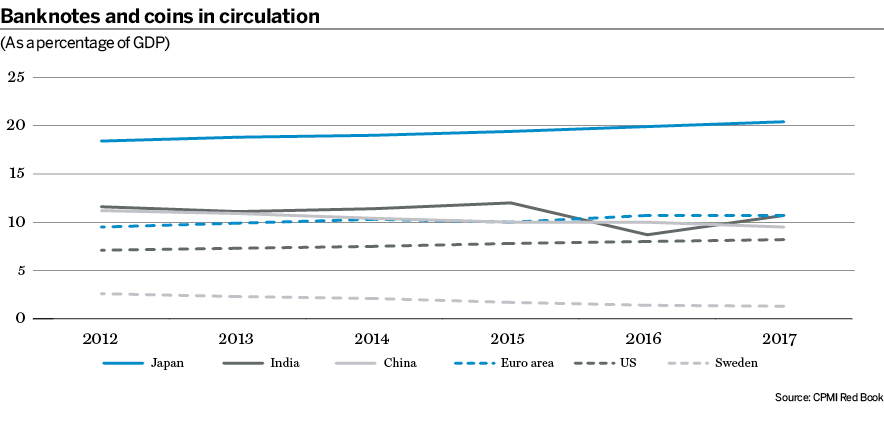

Yet physical banknotes and coins persist, even in the most digitally advanced countries. According to the Red Book statistics, cash in circulation varies considerably across CPMI member jurisdictions, ranging from 1.4% of GDP in Sweden to 20.6% of GDP in Japan, and is above 5% of GDP in two thirds of CPMI countries. Japan, the UK and the US, for example, continue to see a steady rise in cash in circulation. Even India, which carried out a demonetisation drive in November 2016, has seen cash in circulation increasing again, to 10.7% of GDP.

“Often there is an exaggeration in the media about cashless societies,” says one US expert, who asked not to be named. “In the US, we aren’t experiencing cashless-ness in any real sense. We have 43 billion physical pieces of cash in circulation worldwide. We aren’t even in a decline – we are in a growth mode.”

And there is a sizeable section of society that reportedly does not want to make the transition. A recent Travelex survey of four markets – the UK, Australia, Brazil and South Africa – found an “immovable” 24% of consumers who will never abandon cash, “no matter what technological advance or leap forward is available to them”. Likewise, in ING’s 2017 survey about three-quarters (76%) of the respondents in Europe said they will never go completely cashless.

“People choose cash for a whole variety of reasons. It could be because they find it useful as a budgeting tool, or because it is simple for them to use, or because it works when other payment means don’t. It is important that people are able to make the choice to continue to use cash if they want to,” says Sarah John, chief cashier and director of notes at the Bank of England (BoE).

Leif Veggum, director, cashier’s department, at Norges Bank, agrees. “As a central bank, our view is that the users should decide. We are neutral when it comes to how people pay, but think it is important that the users can choose between different solutions Therefore, it is important that cash is available as an option,” he says. Norway passed legislation in 2016 to enshrine in law the obligation that banks have to provide cash services to their customers.

Taking notes

Both the BoE and Norges Bank recently rolled out new banknotes. “We think that as long as cash is used, it is our obligation to supply banknotes that the users can trust, meaning that they can easily check that the banknotes are genuine. We don’t want Norwegian banknotes to be less secure or easier to counterfeit than in nearby countries,” says Mr Veggum.

But does this investment make sense considering a future with less cash usage? Ms John is often asked this question. “The short answer is that cash is likely to remain an important means of payment for a significant number of people for many years to come. My job is to make sure that the public has high-quality bank notes that they can use with confidence, and one element of that is that they can’t be easily counterfeited,” she says. “The move to polymer means that the notes we are issuing now are going to be cleaner, safer and stronger than previous paper notes, and that is absolutely worth the investment because cash is here to stay for at least the foreseeable future.”

And Wolfram Seidemann, chief executive officer at G+D Currency Technology, adds: “Banknote features today are more intuitive and easier to authenticate, but increasingly more difficult to replicate. The latest notes issued by central banks are more attractive, brighter and intuitive, with dynamic security features, so that people have confidence in the currency.”

Contingency, privacy and acceptance

Ms John touched on one of the reasons cash remains pervasive: it works whether or not the electricity is on, the internet is up or there is mobile reception. Digital systems may be 'convenient', but they often come with central points of failure – and many point to the Visa outage in June 2018 as a prime example.

As such, banknotes are an important emergency or back-up payment instrument. “It is not possible to depend on other forms of payment unless the infrastructure is there to support them with 100% confidence that they will always work,” says the US expert.

In a staff discussion paper, 'Is a cashless society problematic?', published in October 2018, the Bank of Canada noted that “given the increased dependence on retail payment networks in a cashless society, concerns might arise with regard to the maintenance of operational reliability... As well, there could be a need to provide a safe store of value in an (extreme) financial crisis.” The US expert points to the situation in Puerto Rico following the devastation from Hurricane Maria, saying: “Cash was the only means of payment during that crisis.”

Anonymity is another attribute of cash that a digital equivalent has yet to replicate, with many raising concerns around the surveillance implications of a cashless society. “It is important for society that at least there is the possibility to not be financially monitored for every single purchase made, which is what happens when everything is moved to micro-transaction-based, contactless payments services,” says Linus Neumann, senior IT security consultant at Chaos Computer Club, which is Europe's largest association of hackers.

The universality of cash is a third characteristic that has not been replicated to date. In fact, with a plethora of digital payment methods coming to market, interoperability is viewed as a major challenge going forward. “There is a risk of developing artificial segregations and potential inefficiency in the economy if there are many competing payment systems that are non-compatible – it is not efficient for retailers to use multiple systems,” says Paul Donovan, global chief economist at UBS Wealth Management.

Problems of exclusion

Many governments are using e-payments, and more broadly digital financial services, to accelerate financial inclusion and bring the unbanked into the formal financial system. This will help drive faster progress towards the UN’s 2030 Sustainable Development Goals, including eliminating poverty and hunger to clean water, affordable energy and climate action, according to a compendium published by BTCA and the World Bank, alongside other organisations.

However, there is also concern that a comprehensive shift to digital could exclude large sections of society. Revolut’s Mr West believes this is an important consideration. “There is a big audience out there that is not digitally savvy, who is more dependent on cash given the infrastructure in the communities. It is good to dream about what the future will look like, but we can’t force everyone in the UK to suddenly go cashless,” he says.

Central banks are keenly aware of the many challenges posed during a transition period. Ms John says: “It is inevitable that we will move closer towards a cashless society over the next few years and we need to think about how we can manage the transition process so that people aren’t left behind as we move to whatever that future state might be.

“It is the case that the cash network we have in the UK was designed with much higher transactional use of cash than we now have and, indeed, are likely to have in the future. The BoE is working with industry to understand how to design a sustainable cash network for the future, to remove excess capacity, duplication of resources and make it as efficient as possible so that we can maintain as broad a network as possible.”

With an estimated 2.7 million people entirely reliant on cash, the UK launched a six-month independent ‘access to cash’ review in July 2018, calling for evidence from individuals, consumer groups, community representatives, small businesses and industry. The findings are expected to be published in the first half of 2019.

To promote responsible digital payments, BTCA published a set of guidelines in July 2016. “We advocate for moving away from cash to digital payments when there are strong benefits for customers and done responsibly, which goes beyond consumer protection,” says Dr Ruth Goodwin-Groen, BTCA managing director. “The guidelines champion good practices such as transparency in fees, protecting client data and ensuring client recourse. These are essential to instil the trust needed in everyday transactions across the globe, whether it is a woman in Bangladesh receiving a payment from her factory, or a farmworker in Ghana in the cocoa value chain.”

Central bank digital currency?

Christine Lagarde, International Monetary Fund (IMF) managing director, made waves at the Singapore Fintech Festival in November 2018 when she advocated for central banks to consider issuing digital currencies, effectively promoting the state’s role in supplying money to the digital economy. According to the IMF note published the same day, entitled 'Casting light on central bank digital currency', a central bank digital currency (CBDC) could be the “next milestone in the evolution of money”.

“This currency could satisfy public policy goals, such as financial inclusion, and security and consumer protection; and [it could] provide what the private sector cannot: privacy in payments,” said Ms Lagarde. Already, numerous central banks around the world are exploring CBDCs, including in Canada, China, Sweden and Uruguay. The BoE also has a dedicated research programme looking at this possibility.

Ms John has an open mind regarding the development of a CBDC. “At this time, it is not clear that the benefits of a CBDC from a monetary and financial stability perspective would outweigh the risks that it would introduce. It is important that we weigh the costs and benefits very carefully in this space. There are also some broader societal questions that we would need to answer, so it is not a decision that the BoE could make alone but one we would need to consult with others before going down that route,” she says.