ATM malware attacks are on the rise and gaining in sophistication and scale, yet historic threats persist, including skimming and brute force attacks. How can banks best defend their ATM networks? Joy Macknight investigates.

It is 5.30am on a Monday in central Taipei. A man walks up to an ATM near Siping Street Market and waits a few moments before the machine spits out 40 bills. He collects the money and vanishes in the dawn light. At the same time, this identical sequence is being played out at multiple ATMs across the city.

When the operation is complete, remote hackers wipe the malicious program, or malware, off the compromised ATMs. A few months before, they had installed the malware through phishing emails sent to the bank’s employees, which allowed them to gain access to the bank’s network and sub-networks, such as its ATM estate.

This is how cybercriminals stole T$83m ($2.6m) through 41 compromised ATMs from First Commercial Bank in July 2016 – without using cash cards or even touching the PIN pads, according to a forensic study by Taiwan’s Ministry of Justice Investigation Bureau.

Hitting the networks

A similar modus operandi has been uncovered in other network-based ATM malware attacks, such as Cobalt Strike, Anunak/Carbanak and Ripper, and signals a progression from the manual installation of malware on ATMs to hacking into the financial institution’s corporate network.

Steven Wilson, head of the European Cybercrime Centre (EC3) at Europol, says: “In the past year, we have seen significant attacks against the ATM infrastructure. This is the most sophisticated type of attack, targeting the command and control systems of ATMs and giving illegal cash-out orders.”

Marcin Skowronek, head of the cyber fraud team at EC3, adds: “This type of attack is considered as the major threat due to its nature, including international dimension, sophistication, challenges to respond/prevent, and its potential to impact the banking sector’s reputation.”

A September 2017 report by EU law enforcement agency Europol and cloud security company Trend Micro, entitled ‘Cashing in on ATM malware’, provides a comprehensive look at known ATM malware families and different logical attack types, both physical and network-based. ATM malware attacks include cash-out (or jackpotting), man-in-the-middle and virtual skimming. Those ATMs with outdated or non-supported software are particularly vulnerable.

The report also identifies shared characteristics of the perpetrators. The main threat is coming from organised criminal gangs with expert knowledge, significant skills and resources at their disposal – described by Mr Wilson as “cybercrime as a service” – where many of the felonious activities are subcontracted out. Second, these gangs are well-coordinated, with money mules on the ground while hackers and masterminds sit in other countries. They are also internationally connected and can quickly export successful attacks to other jurisdictions.

“The criminal industry is global in terms of sharing information with each other, communicating ATM vulnerabilities, exploiting them at scale and replicating these attacks across the world very quickly,” says industry expert Francesco Burelli. “This indicates that the criminals are either connected or they are selling information to each other through forums.”

Threat vectors

While malware attacks are becoming more common and increasing in scale and scope, Steven Jacob, partner and director at Arkwright Consulting, points out that physical attacks against ATMs have never ceased. “Attacks targeting the payment credentials of the cardholders, for example, are still taking place, but as the industry keeps progressing towards EMV [global standard for chip-based cards], these types of attacks are becoming less prevalent than in the past,” he says.

Skimming – installing a device to capture data from the magnetic stripe of a customer’s card – remains the most prevalent ATM attack method globally, according to ATM Industry Association’s (Atmia’s) Global Fraud and Security Survey 2017. “The technique of deep-insert skimming [a paper-thin device hidden inside an ATM’s card acceptance slot] was recognised as the method increasing at the fastest pace, followed by ATM malware for card data,” says Mike Lee, CEO of Atmia.

Turkey is one country where card skimming persists because most debit cards are not yet EMV-compliant, according to Mehmet Ozdogan, assistant manager at Türkiye Is Bankasi. On the other hand, it has not seen more sophisticated attacks, such as jackpotting. “Because fraudsters can counterfeit cards, they don’t need to evolve their threats against ATMs,” he says. However, he predicts that Turkey will see a rise in logical attacks in the next few years.

In other parts of Europe, losses attributable to card fraud are now at their lowest level since 2005, according to the most recent report by the European Association for Secure Transactions (East), covering the first half of 2018. This is primarily due to a decline in card skimming. East executive director Lachlan Gunn said in a statement: “The significant drop in card skimming incidents and losses reflects the continued effectiveness of EMV, as well as the work that has been put in by payment terminal deployers and card issuers with regard to countermeasures such as geo-blocking, fraud monitoring capabilities and fraud detection.”

Brute force attacks, such as ram raids, burglary or explosives/gas attacks, continue to increase in some jurisdictions. For example, there was a 21% year-on-year increase in such attacks against European ATMs reported in 2017, according to East.

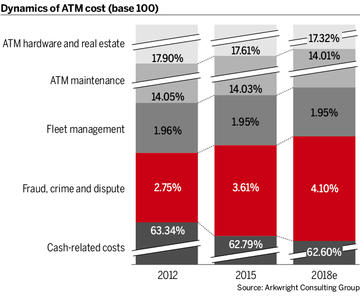

The cost of fraud, crime and dispute is increasing year on year, at a time when other costs related to the ATM estate are remaining consistent

Protective measures

Defining the proper mix of security and monitoring solutions for each of the various parts of the ATM estate based on location, access, exposure and so on, together with the suitable cash management approach, “are all key components to make the ATM a less easy or attractive target for criminals”, says Mr Jacob.

Mr Skowronek says deciding on an appropriate defence method needs to start from the problem. “For example, skimming affects cards that aren’t EMV compliant, so banks can use geo-blocking as a solution. If it is a black box attack – or communication between a phone or computer that is giving orders to the cash dispenser – then the bank should use encryption during communication within the ATM unit. For attacks on ATMs with cards whose limits are manipulated, then the answer is live monitoring of ATM transactions. Cash trapping, which is a substantial part of ATM fraud, needs physical monitoring of ATMs. The short answer is: specific measures depend on specific criminal techniques.”

Remote monitoring for unusual ATM device behaviour has grown in importance in fraud prevention measures, jumping from 18th to fourth place in relevance between 2014 and 2016, according to Atmia’s ATM benchmarking survey. Arkwright’s Mr Jacob says: “The increased ability to monitor the activity of the ATM where an alert is raised at specific occurrences and the ability to monitor the actual ATM unit and its immediate surroundings are areas of recent industry focus.”

Matt Phillips, vice-president of banking, the UK and Ireland, at finanical technology company Diebold Nixdorf, also highlights the effectiveness of ATM monitoring. “If a criminal has tampered with the ATM’s cash dispenser, for example, a bank can use monitoring tools to verify that no one has put a card into the machine nor started a transaction and then quickly shut down the machine. Equally, once the threat has been mitigated, the machine can be brought back up, so it is available for the next customer.”

Is Bankasi’s Mr Ozdogan advocates that the industry moves away from plastic cards with magnetic stripes – “technology of the 1980s” – and builds services compatible with mobile banking applications. “Today, most customers can withdraw cash by mobile phone using a QR code on the ATM screen and logging in through a mobile banking application,” he says. “We must get rid of the plastic cards – they are costly and bad for the environment.”

Big data in Brazil

Emerging technologies, such as artificial intelligence, biometrics and big data analytics, are also helping in the fight against card fraud, malware and other cyber-attacks. A real-life example of the latter is Banco Bradesco’s big data project to prevent attacks across its 38,000-strong ATM network, which picked up The Banker’s Tech Projects cyber security award in 2017 for its efforts.

The Brazilian bank has developed specific algorithms to assess the network. The first algorithm analyses the ATM network information to understand behavioural patterns. The second algorithm identifies any change in configuration, to identify if a thief or hacker is preparing an attack. It analyses all files and software programs running on each ATM machine periodically to identify possible breaches.

Before the project, the ATM network generated more than 100,000 false alarms a week; now the real-time sensor algorithm has reduced this to 60 incidents a week. The solution can also determine the attacker’s next target, which helps the bank reduce the attack impact and increases the number of machines available for customers.

According to Fabrizio Pinna, executive superintendent at Bradesco, the bank has diminished the hackers’ effectiveness. “Before big data, my greatest pain points during an attack was finding the next machine that would be attacked and determining the size of the attack,” he says. “In the most recent attack, by using big data we discovered that a small number of machines were identified as target candidates. This meant we could mitigate the threat by removing the money, alerting the police, or just switching off the machines.”

Greater collaboration

To stay a step ahead of criminals, banks must leverage industry collaboration platforms, such as Atmia, says Mr Burelli, to alert each other when something is going wrong and maximise the efficiency of the response or prevention measure. Atmia has an online library of end-to-end best practices for ATM security, which is available to members.

“We have security forums and an ATM cyber security alliance, with law enforcement representation, as well as ATM crime data analysis and annual fraud surveys to identify key threats on an ongoing basis,” says Mr Lee. Atmia is joining forces with the ATM Security Association to create a global ATM security platform from 2019 onwards, including shared resources, coordination of activities, data analysis and development of new security standards.

Europol’s Mr Wilson also emphasises the benefits of sharing information within the industry. “We have a financial services advisory group, where major banks are represented, and a regular topic is the threat against ATMs. That is why we are starting to succeed in targeting some of the main gangs involved in this activity.”

Additionally, Europol has built close ties with law enforcement units internationally, especially in the US and south-east Asia. “We have been able to do joint training, which has directly led to arrests in these countries. Effectively, we now have officers across the world employing the same tactics to target the groups who are hacking machines in one jurisdiction but cashing out in others,” says Mr Wilson.

The move to prevention

In a big coup in March, Europol worked with the US Federal Bureau of Investigation, the Romanian, Moldovan, Belarussian and Taiwanese authorities, Spanish National Police and private cyber security companies to arrest the mastermind of the cybercrime syndicate behind the Carbanak and Cobalt malware attacks, which targeted more than 100 financial institutions and resulted in €1bn in losses for the industry. (Not all of the losses were due to ATM attacks alone but it illustrates the potential scale of network attacks.)

The co-operation between law enforcement and the financial sector has meant the industry has been able to move from crime detection to prevention, says Mr Skowronek. “The first attacks in 2015 were detected only after the illegal transactions – the ATM cash-outs – took place. But since 2017 we have managed to detect at the malware penetration stage. Together with security companies we managed to identify which perspective batches were targeted and stop the criminal activities before the cash out,” he says.

Later in November, Europol – in association with East, ATM manufacturers, ATM security companies and Interpol – will be issuing updated guidance and recommendations regarding logical attacks on ATMs specifically for law enforcement and the financial sector.