Step in the right direction: SBI's operations have benefited from its huge technology overhaul

In response to pressure from the Reserve Bank of India, Indian banks have made huge investments in modernising their IT infrastructure during the past 10 years. But there is still much work to be done, particularly around customer relationship management, payments and financial inclusion. Writer Rekha Menon

Eighteen months ago, India's largest bank, the government-backed State Bank of India (SBI), concluded a huge and extended computerisation exercise that it had initiated in 2003. The branch automation platform at SBI and its six associate banks was replaced with a centralised core banking system in one of the largest core banking migrations undertaken globally. Analyst firm Celent, which has written a report on SBI's technological overhaul, estimates that the programme involved 17,500 branches, 20,000 ATMs, more than 260 million accounts and 37 million peak transactions a day.

Unlike the earlier system that was implemented in a distributed manner with branch-level processing, the new core banking platform has centralised operational functions, ensuring unification of all processes across the State Bank Group. "Today, a customer is a customer of the bank, not a branch," says A Krishna Kumar, deputy general manager for IT at SBI. Commenting on the impact this technology renewal has had on the bank, he asserts: "State Bank of India today is not what it was 10 years back."

This last statement is applicable to the entire Indian banking sector. Over the past decade, technology has helped to dramatically transform the face of Indian banking. But while mass-scale IT modernisation has dramatically improved operational capacity, there is still much work to be done, particularly where customer relationship management (CRM), payments and financial inclusion are concerned.

Private sector revolution

Banking in India was mostly manual until the 1970s and even the 1980s. Around the mid-1980s, when banks first started computerisation, the pace of automation was very slow, largely due to sub-optimal infrastructural issues, opposition from trade unions and a lack of interest from the top management. Regulatory intervention in the form of high-level committees under the chairmanship of Dr C Rangarajan, then governor of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), the country's central bank, that strongly recommended automation of the banking, did to an extent help the cause. However, although a few banks did take to computerisation, they opted for disparate branch automation solutions.

This uninspiring automation landscape changed dramatically in the mid-1990s with the advent of a handful of new private sector banks such as ICICI Bank and HDFC Bank. A pre-condition of receiving bank licences was a mandatory deployment of technology, which they used to their advantage. Private sector banks aggressively adopted technology to compete against well-entrenched players that had vast branch networks. Although most of the new banks started with a decentralised branch automation model, they were among the first in the market to move to a centralised core banking solution in the early 2000s. All along, these banks offered anytime, anywhere banking through electronic delivery channels, rapidly introduced new products and, most importantly, focused on customer convenience.

This was a paradigm shift for the average Indian retail customer so far exposed to indifferent, lackadaisical banking services and they gravitated in large numbers towards these new private sector banks. A plethora of economic liberalisation measures in the early 1990s had transformed the Indian middle class and the tech-savvy new players were able to capture the imagination of the rapidly burgeoning urban middle class segment. Despite their much larger branch network, the older banks not only saw their existing customer base being eroded, they also found that they were unable to attract new customers. In the corporate banking segment, foreign banks with their superior automated platforms gained market share.

Today, ICICI Bank, HDFC Bank and Axis Bank, the front-runners among the new private sector brigade, are ranked among the top 10 banks in the country.

Core banking shift

Technology is the bedrock of ICICI Bank, says Pravir Vohra, the bank's group chief technology officer. ICICI, which is the second largest bank in the country after SBI, has about 1600 branches, 4700 ATMs and 27 million customers that actively use alternative delivery channels. Only about 11% of ICICI's transactions take place in the branch today, says Mr Vohra.

At Axis Bank, which has about 1000 branches and 3600 ATMs, the 11 million retail customers conduct nearly 94% of all transactions through an ATM or online. Sisir Chakrabarti, executive director for retail banking, small and medium-sized enterprises and agribusiness at Axis Bank, says: "The bank was established in 1994 and, going by RBI guidelines, we were fully computerised from day one. Initially we were on a distributed platform, but when, in 2000, we moved to core banking, our ability to reach clients seamlessly across all geographies increased manifold. We were also able to offer innovative products in the area of cash management and internet banking."

Finally, in response to competitive threats and regulatory mandates, the older banks started actively modernising their systems. Falling hardware costs along with an improved telecommunication infrastructure also helped the cause.

Dr KC Chakrabarty, deputy governor of RBI, says: "Technology adoption in Indian banking happened primarily as a response to a business push. Older banks were forced to implement modern technology to deal with the competitive business environment created by the new private banks. At the same time, regulatory diktats by the RBI helped bank management counter resistance from trade unions."

Over the past decade, domestic Indian banks have made huge investments in modernising their systems. RBI estimates that from September 1999 to March 2009, public sector banks invested Rs18,168 crores (one crore equals ten million rupees) ($4bn) in computerisation and development of communication networks. Centralised core banking is now the norm rather than the exception and public sector banks have caught up, or in some cases even surpassed their private banking counterparts in their technological efforts. The RBI estimates that by the end of March 2009 almost 80% of public sector bank branches were already on core banking systems.

The main benefits of a core platform are 'anywhere' banking, process efficiencies and product innovation, says Haragopal M, global head of Finacle at core banking technology vendor Infosys Technologies. With core banking adoption, banks have seen their existing footprint deliver much more business, he says. "In the past 10 years, India's gross domestic product grew by 175% to 180%. But bank deposits and loan portfolios in this period saw a 400% to 500% growth, with a minimal increase in the workforce. A leading bank CEO told me recently that ever since he implemented the core banking system, business grew by three times, while the workforce has actually reduced."

SBI has experienced tremendous growth in business volumes and an increase in overall productivity as a result of its technology upgrade, says Krishna Kumar. Reportedly, between 2004 and 2009, the business per employee at SBI increased by 250%. Mr Kumar says that a key benefit of SBI's core banking initiative is process standardisation, adding: "Earlier, processes varied between branches but centralisation has brought uniformity in operations."

Dr KC Chakrabarty, deputy governor of the Reserve Bank of India

A Krishna Kumar, deputy general manager for IT at the State Bank of India

Pravir Vohra, group chief technology officer at ICICI Bank

Beyond customer acquisition

With the basic computerisation infrastructure in place, some of the leading Indian banks are looking at other technological initiatives. ICICI Bank, which has invested in the areas of risk control, analytics and business intelligence, is now focusing on "enriching these existing applications". SBI, on the other hand, is building a data warehouse with IBM in order to gain a "scientific understanding" of customer behaviour. Other technology initiatives at SBI include replacing its existing ATM switch and creating a payments hub.

Dr Chakrabarty of RBI says that banks need to focus on improving their internal processes. "Although banks have managed to enhance their back-end transaction processing, they still need to improve their internal managing information systems and audit-trail reporting," he says. Understanding customer data is also a key technological imperative for India's banks, going forward, says G Srinivasa Raghavan, country head for India business at banking technology vendor TCS. "Banks need to ensure accuracy of data and then figure out ways of utilising this data for enhancing the business and customer service."

Joydeep Sengupta, director of McKinsey in India, also highlights the need to be more customer focused. Technology modernisation at Indian banks has so far been more inward-focused, on improving operational efficiency rather than being customer friendly, he says, "The past 10 years was an era of sheer growth. Now banks need to go beyond customer acquisition. More thought needs to go into servicing this customer base and enhancing the wallet share." On average, banks in India sell only 1.2 products per customer. This cross-sell ratio can be increased by enhancing CRM efforts, he says. In the US and Europe the average cross-sell ratio is two or three, with some banks claiming a cross-sell ratio as high as 5.5.

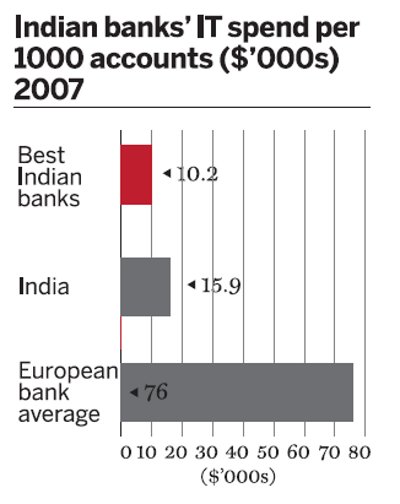

An area where Indian banks have an edge over their peers in developed nations is their modern technology infrastructure. By coming late into the tech scene and boasting the latest technology platforms, many Indian banks have managed to leapfrog legacy system issues that continue to trouble banks in Europe and the US. A 2007 benchmarking survey of leading banks in India by McKinsey revealed that the best banks in India are the most technology-efficient in the world, spending less than $11 per account on IT systems and services, compared with an average spend of $76 per account in European banks.

"From a cost and efficiency perspective, Indian banks are at an advantage in general, but from an application perspective the degree of sophistication is not yet good enough," says Mr Sengupta, explaining that banks in the US and Europe are much further ahead of Indian banks in areas such as CRM applications, corporate cash management, trade finance systems and payment systems.

Cash dependence

Mr Chakrabarti of Axis Bank complains that a key challenge for banks in India lies in the payments space: "Banks need to reduce their over-dependence on cash and cheques and encourage electronic and plastic payment transactions."

The RBI has, over the past two decades, been assiduously working to develop and promote an electronic payments infrastructure in the country. To that effect, it launched the Electronic Clearing Service (ECS) for low-value credit and debit payments in 1995. In 2004, it introduced the Real Time Gross Settlement (RTGS) system for large value payments, while the National Electronic Funds Transfer (NEFT) system was launched in 2005 as a way for customers to transfer funds between banks. RBI is also piloting a cheque truncation system.

Over time, the bank/branch network coverage of these electronic payment systems has increased, but the growth in retail electronic payment transactions is not fast enough, according to Mr Chakarabarti. "Today, about 70% of retail payment transactions are through cash or cheque," he says. ECS is gradually becoming popular for payments such as dividends, but not for utility payments, he adds. While RTGS and NEFT are popular with larger companies, the need now is to onboard customers at the small business and retail level.

Reaching rural India

Mr Chakrabarti says that another technological challenge for Indian banks, going forward, is financial inclusion: "We need to find a low-cost technology-based solution to reach out to the rural and urban poor."

Much of banks' efforts today in leveraging technology, from CRM and data warehousing to payments, is geared towards servicing urban customers. However, a significant majority of the Indian population lives in villages. The banking regulator has, in recent years, been pressurising banks to enhance their rural banking services as well as to work on financial inclusion. Industry experts suggest that including this population in the banking system will not only fulfil a social obligation, but has revenue-generation potential as well. The trick is in putting in place the right business model at a low cost. Technology remains the lynchpin for initiatives in this sector as without technology it would be impossible to provide low-cost banking services across the vast rural hinterland of India.

Several banks are piloting projects based on smart cards and mobile banking in the area of financial inclusion and it still remains to be seen which business model will finally emerge. Regarding rural banking, the RBI has directed the 86 regional rural banks in the country to move their 15,000 or so branches to a core banking platform by 2011.

Infrastructure obstacles

One of the biggest challenges in rural areas remains infrastructure, or the lack of it, says Mr Kumar of SBI. "Infrastructure in rural areas is still a big issue. Many places don't have a regular supply of electricity, while many places do not have telephone lines, so we have to set up satellite dishes there. The cost of running an operation in these places is very high." With SBI's social agenda of extending the banking service across the country, almost 35% of its branches are in rural areas and another 30% in semi-urban areas.

In an innovative step, SBI recently announced plans to roll out 300 solar-powered ATMs in rural areas, the first large-scale deployment of its kind in the country. These solar powered ATMs are said to consume less than 5% of the electricity that a normal ATM consumes.

Ashvin Parekh, partner and national leader for global financial services at Ernst & Young, supports this move by SBI. Such technological innovations will make financial inclusion and rural banking a successful reality in India, he says. "Even three years ago, all the technological innovation we would see in the country would come from foreign banks. It is heartening to see domestic banks come up with such innovations that are uniquely tailored to help banks meet the challenges of the Indian market."