Filling Asia's vacuum

Willem Klaassens, global head of commodity traders and agribusiness at Standard Chartered Bank in Singapore

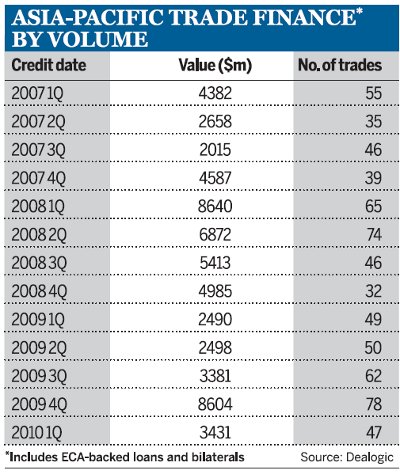

As international banks have pulled back their trade and commodity finance operations in Asia during the downturn, so increasingly sophisticated local players, particularly in China, are piling in. Writer Charlie Corbett

After the initial shock of the banking collapse in October 2008, it was only in 2009 that the full implications were felt. The collapse in trade volumes and the disappearance of bank financing, particularly in emerging markets, acted as a hydraulic break on the global economy.

Asia, which had previously been assumed to have 'decoupled' from developed markets, did not escape. Demand for the region's exports dried up and, with no substantial internal demand to fill the void, companies and commodities producers across the region suffered.

According to statistics from the International Monetary Fund, in the fourth quarter of 2008 gross domestic product in Asia (excluding China and India) plummeted by close to 15% on a seasonally adjusted annualised basis.

A simultaneous fall in bank flows among major global banks and a collapse in dollar funding, combined with the fall-off in demand for both manufactured goods and commodities, contributed to a contraction of exports in 2009 by 30% in some Asian countries, and by up to 40% in Japan.

World trade collapsed by some 12% in 2009, according to the World Trade Organisation (WTO), and this was due partly to the tightening of trade finance. Rising liquidity pressures, a scarcity of capital, increased capital requirements and heightened risk-aversion led to ever-increasing lending costs and risk premiums.

Recovery signs

There has been a modest recovery in trade volumes so far in 2010. An optimistic WTO has even predicted world trade will rebound by 9.5% in 2010. In relative terms, however, the worst trade volume for 70 years in 2009 is a low base from which to start.

Asia's developing economies have, to some extent, bounced back from the downturn. This is in large part due to governments across the region boosting spending, reducing interest rates and stabilising financial markets during the nadir of the crisis. Fiscal measures on such a grand scale have staved off the very worst potential calamities of the downturn - as has a timely injection of $250bn-worth of trade finance from the G-20 nations over a period of two years. Efforts by export credit agencies, regional development banks and international banks to establish trade-facilitation programmes, trade-guarantee facilities and export insurance processes have softened the blow for many regional producers and have kept markets open.

China to the rescue

It is difficult to pin down the precise impact of the collapse of trade financing on the financing of commodities in Asia because a distinction needs to be made between value of trade and volume.

"The hard part here is interpretation of statistics. In the second half of 2008 and early 2009 everyone threw their hands up in horror at the collapse in trade volumes, when a lot of what they were seeing was in fact a collapse in trade values," says John MacNamara, head of structured commodity trade finance at Deutsche Bank.

He makes a valid point. A collapse in the price of oil in late-2008 had a big impact on the value of trade, but not necessarily on the volume of trade done.

"If we look at Asia, though, there were also other things going on," adds Mr MacNamara. "Japanese exports of capital goods dropped off the plot because people simply stopped, or at least deferred, buying, and if you're not selling capital goods then you don't need to import the raw materials from which to make them."

Despite the parlous state of Japan's economy, however, demand for commodities across Asia has been sustained by an increasingly voracious China. A fall-off in demand for its products in developed markets has been assuaged by successful government efforts to spur internal demand through various fiscal stimuli.

"We now clearly see a sustained growth driven by domestic consumption and stronger demand in the economy," says Ravi Saxena, managing director and regional head of trade for Asia-Pacific at Citi. "The share of commodity imports of China when compared against global demand has been steadily growing over the past decade."

Mr MacNamara agrees: "I don't see any real impediment to China remaining the number-one buyer of commodities on the planet. It has overtaken Europe, Japan and now the US, and its appetite is voracious.

"Chinese buying through the crisis has kept many commodity producers in other countries from bankruptcy and has prevented the wholesale shutdown of commodity production all over the place, despite the global crisis. You can't help feeling that recovery of the commodity markets has depended on the sustained Chinese buying rather more than the higher-profile Western government rescues of various banks."

However, not everyone believes China's influence on the region is necessarily all for the good; some remain sceptical. "China is attracting huge amounts of commodities into the region and, at some point, needs to start giving back through exports, investments or otherwise," says Willem Klaassens, global head of commodity traders and agribusiness at Standard Chartered Bank in Singapore.

Local players

Since commodities make up such a large part of trade in Asia, financing producers and consumers during the downturn has been critical. The scaling back - or complete withdrawal in some cases - of credit lines by many international banks from the region in 2008 and 2009 had a dramatic impact on the financing of commodities trade, but it also created opportunities for local banks.

"Many clients came to us in need during the downturn as struggling Western banks pulled back from Asia and the commodities business. Those banks were in difficulty and did not have liquidity to give to Asian companies," says Mr Klaassens.

Standard Chartered was one of the few international institutions that did not scale back its Asian operations, mainly because it considers itself an Asian bank, despite being headquartered in the UK.

"Local banks are getting more resourceful. They have never been able to do classic commodity trade finance before," says Mr Klaassens. "It makes sense. They have good relationships with local commodities players and are now starting to leverage these relationships with commodity expertise."

He adds that, for the moment, this is good for business across the region but feels "there is still not enough liquidity in the commodities trade business". His major concern is that a new bank enters the sector with enthusiasm but exits quickly when things become difficult, leading to a liquidity squeeze for the commodity players. This scenario will become increasingly likely if the world experiences a double-dip recession.

Pierre Glauser, global head of transactional commodity finance at Crédit Agricole CIB in Geneva, has no such qualms. "Asia was not hurt [by the downturn]. The banking system was not hurt. For us, Asia is still the most competitive market in terms of financing," he says. "The banks are strong, the banks are liquid, the banks have a good knowledge of the importers and they are really working at reduced prices."

The biggest threat to the global banks' commodities financing business in Asia is likely to come from the emerging, often state-backed, goliaths coming out of China.

"Today our strongest competitors are the Chinese banks because they are liquid and very strong," says Mr Glauser. "It's a big change now to what it was a few years ago. The Chinese banking system is a mature one. Everybody likes to work with them."

His sentiments are echoed by Mr MacNamara. "We increasingly see Chinese banks offering literally billions of dollars of very long-term financing, up to 25 years in some cases, based on the commodity export flow being routed to China. It's difficult to compete with that," he says.

Getting connected

Stiff competition is not only emerging out of China. DBS Bank in Singapore, for example, identified big opportunities to grab marketshare as the international banks withdrew credit to the sector during the downturn.

Tom McCabe, head of global transaction services at DBS, sees a number of major factors influencing trends in the industry. The first is the underlying demand for commodities. "We have nearly 400 million people entering the middle-class in Asia, which means more demand for homes, automobiles and food," he says. "Second, you have the effect of the crisis on the global banks' balance sheets, which is limiting their ability to meet customer growth needs."

Mr McCabe says that banks such as DBS now have the necessary scale, liquidity and sophistication to take on the big guns.

"DBS' franchise has an extensive network across Asia, we have a stronger balance sheet, high liquidity and carry better capital ratios than most of the global banks," he says.

While local banks continue to build up their operations in Asia, however, one area where they struggle to compete with the international banks is in their global distribution capabilities.

Mr Glauser admits that local banks know their customers better and offer very competitive rates, but says that Crédit Agricole's competitive advantage, as a European bank, is in its worldwide network. "We have specialised teams that know every facet of the business, which is not necessarily the case with regional players," he says.

The issue of talent is also a problem for regional players: they simply do not have the necessary human resources to compete with the traditional players, a point that Mr McCabe concedes: "The industry challenge [in Asia] is the dearth of seasoned, experienced professionals to meet the end-to-end needs in this segment."

Developing market

Looking ahead, the big challenge for those banks looking to capitalise on the growth of commodities finance in Asia lies in the scale and nature of the deals. The only source of financing available to most regional commodities players in Asia is through traditional structures, such as letters of credit and pre-export finance. Such deals tend to be small in scale - a state of affairs that has been reinforced by the downturn.

"The letter of credit, whose departure from the global trade finance scene has been announced with such certainty so many times in the past decade or so, made a rude recovery to form during the crisis and even quite well-known names were required to provide them in order to get goods," says Mr MacNamara.

This situation is unlikely to change any time soon. Access to international equity and debt capital markets will remain closed for all but the biggest companies.

The smaller players will still have to acquire their financing by more traditional; means, according to Mr Klaassens. "Financing the old-fashioned commodity way, short-term and secured, proved stable during the recent crisis. Transactional deals allowed us to keep closely in touch with our clients and track each trade with every player in the value chain. This has been critical in difficult times."

Small, structured deals, however, mean small margins. According to Mr MacNamara, Asian commodity finance deals stubbornly remain much smaller than those in other geographies such as Russia, the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) or Africa. "The structure of the commodity business is rather different in Asia, in particular because either you lack the very large - often former state monopoly - producers on the scale you see in the CIS, Latin America and parts of Africa, or the ones you do see, such as Petronas, are 'too good' for commodity trade finance," he says. "In Asia, a $100m deal is still seen as quite a good-sized deal. That's not to say that the smaller Asian deal is any less work, so you have to do many more deals in commodity trade finance in Asia to make the same sort of money."

The future looks bright for those banks actively involved in commodities finance in Asia. China's appetite for raw materials does not look like being satiated any time soon and this will likely prop up demand in the continent for many years to come. Despite proving not to be quite so decoupled to the global economy as many once believed, the global economic downturn did not affect Asia in the same way as it did the rest of the world.

"The great thing about commodity trade finance is that it never disappears altogether. People still need to eat, drive and make things, so by financing commodity flows we very literally support real jobs in real mines, refineries, farms and factories," says Mr MacNamara.

Asia's banks have emerged from the downturn stronger, with bigger balance sheets and more confidence to take on the traditionally dominant international banks. As Asia develops, so international banks will face ever stiffer competition when it comes to financing commodities trade in the region.