New ways to finance trade

In response to restrictive regulation, trade finance securitisation deals are starting to materialise and, with these deals structured in such a way that they reduce risk weighting, lower leverage and increase liquidity, appetite for them is growing.

Banks are turning to new structures to finance trade, which is partly a response to Basel III regulations. Ironically, a consequence of the regulatory regime – prompted by the financial crisis – is that banks are considering offloading some of their safest assets and turning to securitisation, which acquired a bad name precisely because of the crisis.

“Trade finance securitisation has been a theme of discussions for a while, but only now are we seeing transactions materialise and happening,” says Axel Miller, a partner at consultancy Oliver Wyman.

Kah Chye Tan, global head of trade finance securitisation at JPMorgan, says the need for trade finance securitisation will grow in the years to come. This, he says, is because world trade will continue to grow, banks are now subject to more restrictions on their capital and “the need to find an additional source of liquidity will only be heightened”, and also because there is ample liquidity in the marketplace among institutional investors.

A Basel report estimates that up to one-third of the world’s trade is currently financed by the largest global banks. And data from Dealogic shows a mix of US, European and Japanese banks dominating trade finance in all regions, with emerging markets featuring prominently in the rankings. Asia relies the most on trade finance – data from Swift shows that the region accounts for the majority of import and export letters of credit (LCs) – and the Basel report notes this reliance is greater than the region’s share of global trade.

Problem solving

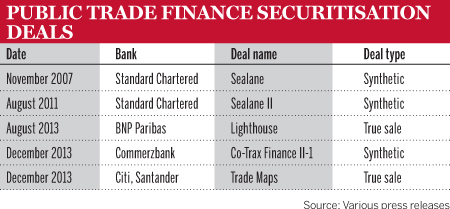

In 2013, a handful of banks – BNP Paribas, Commerzbank, Citi and Santander – announced securitisation deals, which were a mix of synthetic deals and outright securitisations. One industry expert says that the structures are broadly trying to solve three different problems from a capital perspective.

The first problem is to reduce the risk weighting of the trade finance assets. If, for example, a bank has lent to a customer and the transaction has a high risk weighting, the bank can sell the risk to an institutional investor, such as a pension fund. The bank is effectively swapping the risk of its customer with the lower risk profile of the pension fund. This, in turn, reduces the risk weighting of the asset and thus the amount of capital the bank needs to set aside for it. This synthetic structure – where the assets remain on the balance sheet of the bank – was used for Standard Chartered’s 'Sealane' deals in 2007 and 2011, and also Commerzbank’s 'Co-Trax Finance II-1' transaction in 2013.

Hans Krohn, head of trade products at Commerzbank, says that the purpose of the Co-Trax Finance II-1 deal was to reduce the bank’s risk-weighted assets after a stress test in 2012 revealed that the bank had to increase its capital. To make the capital ratios better, he adds, the bank decided to offload the assets rather than stop lending to its clients.

The second problem that banks may need to solve is one of leverage. Even though import LCs are off-balance-sheet and are viewed as a guarantee, under Basel III this has to have an on-balance-sheet equivalent to cover the risk of a small and medium-sized enterprise, for example, not paying. Under the new regulations, the industry observer explains, the leverage ratio of such transactions is capped and banks may choose to securitise their trade assets to lower their leverage, rather than provide additional capital against them. This also has the knock-on effect of also lowering their risk-weighted assets.

In the first of the examples, the bank can reduce its risk-weighted assets on an unfunded basis, but in the second example – of securitising to reduce leverage – the transaction must be funded. This leads onto the third problem that banks may try to solve, which is one of liquidity. In the second example, when the pension fund is providing the bank with cash for the transaction, this also helps the bank meet its liquidity requirements under Basel III.

Putting trade on the map

The funded, true-sale securitisation structure was used for the transactions by BNP Paribas, Citi and Santander. The 'Lighthouse' transaction, launched by BNP Paribas in August 2013, was backed by commodity trade finance loan receivables. The deal, says Fabrice Susini, global head of securitisation at BNP Paribas, is a child of the current regulatory environment in which banks are under pressure – in terms of their liquidity, leverage ratios and regulatory capital – and want to keep servicing their clients.

Tim Conduit, a partner at law firm Allen & Overy, who advised BNP Paribas on the Lighthouse deal, explains that the structure allows the individual assets to be divided up into different risk brackets. The structure has flexibility in it so investors can be exposed to a certain type of risk, for example, by company, country or industry.

Flexibility is a feature of Trade Maps, a multi-bank asset participation programme launched by Citi and Santander in December 2013. Konel Parekh, director of specialised trade at Citi, says the outstanding loans range from $3000 to $30m and the flexibility is not just in the size of the obligor, but also the range of jurisdictions that can feed into the asset pool.

The $1bn inaugural issue of Trade Maps was significant because it was the first multi-bank transaction. When asked why Citi partnered with another bank for this transaction, Mr Parekh says: “We are all competitors but when it comes to efficient balance sheet management, there is no restriction on us working together and opening up a new investor base and to create efficient pricing for everybody."

Fabio Fagundes, head of trade asset mobilisation for Santander, says it is technically possible to have many banks on the Trade Maps structure. However, getting all the banks to the finish line for one issuance is more difficult. “The risk embedded in the structure is very simple short-term trade finance. The operations and legal requirements for this kind of project, with many different jurisdictions, has been quite cumbersome so it will take time for banks to deploy this structure on their own or to join Trade Maps,” he says.

The Trade Maps project was first announced by Citi in 2010, and ING and Santander joined the project in September 2011. By the time the deal was launched, however, ING had dropped out. An ING spokesperson says: “ING decided not to continue with the transaction for several reasons, including adverse market conditions.”

There are many complexities to structuring such a deal. Paul Kruger, a partner at law firm Linklaters, who worked on the Trade Maps deal, says the main issue with this asset class is its diversity, with assets being spread across the world. Unlike an auto loan or residential mortgage securitisation with a single jurisdiction, “here you may be dealing with 50 jurisdictions coming into one deal”, he says.

Mr Conduit at Allen & Overy points out that, unlike mortgages where the loan is secured against a property, “the collateral could either be on the high seas or in an unfamiliar jurisdiction".

Quality control

Mortgages also have a long duration, which makes the management of the asset pool relatively simple. Trade finance, however, is short term and can be between 30 and 90 days. Such a term is impractical for investors and so the securitisation is structured so that the pool of trade finance assets is constantly replenished.

Mr Miller at Oliver Wyman says that maintaining the quality of the assets in the pool is a challenge. He illustrates this point by comparing this asset class with infrastructure project finance, where there could be a 20-year duration and due diligence is only on a single project.

“In trade finance it is short duration and replenishing," says Mr Miller. "As an investor, you cannot do that due diligence on the underlying asset in the same way [as infrastructure project finance], which makes it more difficult. The eligibility criteria and transparency is key. How do you manage the inflow of assets? If you have a bank originating the trade assets and putting them in a conduit, there is an adverse selection issue: you would suspect that a bank puts assets it does not want into the conduit. How do you create, as the originator, a structure and transparency that allows that not to happen, and how can you prove that to the investors?”

Deals such as Trade Maps and Lighthouse have been created with this kind of disclosure in mind. The eligibility criteria, for example, includes limits on the proportion of assets from certain countries or client types. “The eligibility criteria is stringent,” says Mr Susini at BNP Paribas. He adds that even though these are short-term transactions, they are based on long-term, stable relationships between the bank and its clients.

Gregory Kabance, managing director of Latin America and emerging markets structured finance at Fitch Ratings, says there are robust scoring mechanisms in place, and the rating is based on considering the worst-case scenario of what could go wrong.

Risk assessment

Trade finance is considered to be low risk, and figures from the International Chamber of Commerce’s (ICC's) 2013 trade register show that import LCs had a transaction default rate of 0.02% and export LCs a rate of 0.016%. Another reason trade finance is viewed as a good-quality asset is because it has a history of being supported – because it is the life blood of an economy – in times of crisis. “Trade finance has been treated favourably in the past – even when a sovereign defaults it rarely defaults on trade finance,” says Mr Kabance.

However, low risk also means low return for investors. Given the costs of setting up a securitisation platform, is there the potential for the low-risk profile of trade finance to change? And as more investors channel liquidity into this asset class, is there the potential for banks to be less careful about who they are lending to?

“The moment we enter into this type of structure where financial engineering is involved, there is suspicion, which – in the case of trade finance-related securitisations – is unfounded in my opinion,” says Mr Krohn at Commerzbank.

Tod Burwell, president and CEO of industry body BAFT-IFSA, responds to the comparisons that are made with the securitisation of subprime mortgages. “I don’t think anyone expects this to drive another crisis. In terms of the types of assets originated and the types of assets being distributed to institutional investors, the industry is very sensitive to that and there has not been a practice of offloading assets that the bank does not want – there is an interest in maintaining the integrity of the asset pool,” he says.

A report by the Basel Committee on the global financial system addresses the risks of securitisation and notes that “in principle, banks have incentives to maintain their reputations for originating high-quality assets, so as to maintain the returns on their origination expertise. Yet the experience during the recent crisis suggests that these incentives can be compromised by competitive pressures, eroding underwriting standards. In addition, information flow can suffer along the securitisation chain and, in the event of deteriorating asset quality, investors may find it difficult to distinguish the roles played by adverse business conditions versus weakened underwriting.”

Forward thinking

One major difference with trade finance is that because it is short term, problems would be identified much quicker than with mortgages. “These are short-term assets so the sales teams in origination are on top of the market,” says Mr Parekh at Citi, adding that these teams are able to detect the first signs of stress any obligor might face.

“In the next 12 to 24 months, if there is a larger number of securitisations we might see a reaction from the regulators,” says Mr Krohn. “My guess is that if banks get active and inventive we will see more regulations put in place,” he adds. Restrictions have already been put in place. For example, a bank cannot reduce the risk-weighted assets via securitisations at any cost. “If costs exceed the income from the reference pool, the regulator will not give consent to use the instrument for risk-weighted assets reduction,” says Mr Krohn.

Paul Hare, global head of portfolio management at Standard Chartered Bank, believes that regulation is a major hurdle for trade finance to become more widespread. “For synthetic securitisation structures, such as Sealane, the main hurdle is regulation. If implemented, the recent Basel Committee consultation paper on securitisation [CP269] will reduce the amount of capital relief that can be claimed and as a result, some banks may find the cost of synthetic trade finance securitisation transactions too prohibitive,” he says.

But, despite the difficulties and the complexities, many in the industry are optimistic of the future of this new asset class.

Alberto Amo, global head of trade finance at Santander, says: “When we started [the Trade Maps project] we thought were going to have to do a lot of investor eduction. In the past few years, we as an industry have done many initiatives, such as the ICC trade register and product terminology standardisation with BAFT-IFSA, and that helped investors understand this asset class. We were surprised how well the investors received [Trade Maps] and understood it better than we expected – this is good news for the industry. Investors know more about trade and are demanding to be part of the trade finance world.”