Trade finance comes to the fore

The severe slowdown of international trade flows and trade financing during the global crisis have impacted heavily on the export-dependent Latin American economies, yet there are signs that the market is starting to pick up.

The overwhelming and devastating effects of the financial crisis have hit international trade flows hard, with banks contending with weakened balance sheets and limited lending appetite.

The World Trade Organisation forecasts that the collapse in global demand brought about by the downturn will drive export volumes down by about 9% in 2009, the biggest contraction in trade flows since the Second World War. According to the World Bank, the slump in trade finance accounts for between 10% and 15% of the decline in trade so far.

The Latin American region and its banking system entered this crisis in relatively good shape compared with other regions - although no internal factor could prevent the damage to exports that a global economic downturn would wreak. The region has consistently implemented very tight fiscal policies and, as a result of higher commodity prices, many economies had built up high levels of international reserves. At the same time, some of the region's banking systems had significantly strengthened themselves and the local financial market had matured over the past few years.

Local market resourcefulness was key when, at the beginning of this year, international markets were still frozen and foreign banks were firmly entrenched in their home markets. "With the crisis, trades dropped around the world and, in particular, in Latin America," says Jorge Tapia, global head of trade, export and commodities finance at Santander. "Many companies did not have many ways of getting finance. Trade finance was key to support customers' financial needs. It was one of the few ways that companies hit by the crisis had to raise funds."

Only countries with sufficiently developed domestic markets managed to source local financing to support their clients' trade. This is the situation, for example, in Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico and Peru.

Antonio Calheiros, head of trade finance products at Itau BBA, says that trade finance business was not too badly disrupted. "Because we're a very strong commercial bank and have very long-term relationships with our clients, we had huge liquidity during the crisis and we could give continuing financing to clients," he says. "Of course, we had to change our funding from international to local funding, but that wasn't a problem, thanks to our large deposits base and retail operations."

Trade finance appeal

As market troubles evolved and banks' balance sheets became weaker, financiers were forced to choose carefully which products to re-engage with. The useful but certainly not glamorous trade finance structures were ticking many boxes: low-risk and therefore efficient use of capital, short tenors and, for a few months, higher pricing. Although prior to the crisis, an investment grade corporate could source financing at one basis point (bp) over Libor, in the past year this went up to three bps over Libor, only to return to a much lower 1.5bps a few months ago.

If higher pricing was an obvious consequence of the troubles that the international financial markets got themselves into, countries with conservative banks and conservative funding structures had the liquidity to support their corporate clients.

Additionally, to help the dire state of trade flows, international organisations and lending agencies stepped up. The World Bank and the International Finance Corporation (IFC) established liquidity lines for banks active in trade finance.

Significantly, the IFC's Global Trade Finance Programme issued $2.4bn in guarantees in August to support trade with emerging markets, and Latin America was the programme's most active region, representing 35% of its total volume. Beside large users such as Argentina and Brazil, smaller countries participated too and the IFC signed deals in Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Panama, Paraguay and Peru.

Further, the Inter-American Development Bank and the Asian Development Bank have agreed to share access to their trade finance programmes, linking more than 100 financial institutions to support trade between companies in Latin America, the Caribbean, Asia and the Pacific.

Some central banks made a difference too, with initiatives such as the swap line set up by the Brazilian central bank with the US Federal Exchange to increase circulation of US dollars in the local system.

The combination of such initiatives contributed to the resilience of the trade finance product. "At the very beginning of the year, the market was totally frozen and this seriously affected international trade, and of course international trade for a region such as Latin America, which relies heavily on commodities exports, was something very serious," says Valentino Gallo, Americas head of export and agency finance at Citi. "[But] what we also saw at the beginning of the year was international lending agencies. They stepped up and announced special programmes to foster investments."

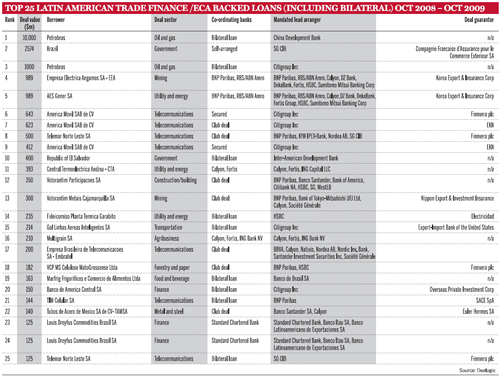

Looking at regional trade finance statistics, however, the situation still appears shaky. Data provider Dealogic reports that the global trade finance and export credit agency-backed loan deal count stood at just 452 in the first nine months of 2009, down from 773 in the same period of 2008 - the lowest first-nine-month level in three years. Volumes dropped by 25% to $92.7bn year on year. In Latin America, deals fell by a much larger 41% to $13.3bn in the first nine months of 2009, despite the colossal $10bn loan to Brazil's Petrobras by China Development Bank, one of the largest transactions of the year.

Hopeful future

In Brazil, the government has set policy measures to support smaller producers - the ones with limited access to funding and higher risk profiles. Experts believe that this is contributing to a more stable market in the country. Government policies and ambitions are also set to generate larger trade volumes for Brazil, particularly in view of new offshore oil field discoveries and their exploitation by state-controlled oil company Petrobras.

Discoveries in the Guara fields last year and the Tupi fields in 2007 - the largest discovery in the region since Mexico's Cantarell in 1976 - will contribute to the Brazilian government's commitment to becoming an oil exporter. Additionally, some oil-related technology, in particular deepwater drilling technology, will need to be imported from outside the region, creating further trade flows. Petrobras' $174bn investment plans will partially be allocated to the acquisition of technology from local and international markets.

Brazil's heavier presence on the world's oil map will also push the country to develop the required state-of-the-art technology. "The potential of the energy sector is good, if oil prices continue to rise" says Walter Molano, head of research at Bcp Securities. "In the meantime, it is creating incentives for the country to be the global technological leader in deepwater drilling."

Furthermore, the telecommunications sector is growing fast and international lending agencies around the world are committed to supporting trade with Latin America. The most indicative example in this space comes from the $1bn financing under negotiation between China Development Bank and America Movil, the region's largest mobile phone operator, controlled by Mexican billionaire Carlos Slim, to facilitate its partnership with China's operators.

Growth is also expected in the agribusiness, led by sugar companies. Consolidation has been taking place and large deals are expected to create international leaders. "Everybody has been expecting [consolidation], but this has been accelerated by the crisis," says Abla Kerdoudi, vice-president of Société Générale's agricultural business in Latin America. "It is a very good thing. Some companies are now the first or second largest businesses in their sectors. The market is in movement. This will encourage [international] banks to come back."

Futhermore, the region's much-needed infrastructure development, together with future sports events - such as the football World Cup in 2014 and the Olympics in 2016, which will both be hosted by Brazil - are expected to generate considerable trade flows and stimulate trade financing.

Rogier Schulpen, global head of commodities finance at Santander

Valentino Gallo, Americas head of export and agency finance at Citi

A matter of time

With a promising future, international banks will not take long to reappear in the market. Although, when exactly this will happen is a matter of opinion. "A lot of banks retreated to their core markets, especially when governments started taking stakes in them," says Rogier Schulpen, global head of commodities finance at Santander. He adds: "Certain banks that were active in Latin America, but didn't consider the region a key market, needed to reallocate their capital in their own countries. Those banks have retreated and we don't see them coming back yet. On the other hand, local banks came out stronger from this crisis. If you look at Brazil, there are some very strong local banks there."

The large local banks that dominate the Brazilian market - and the whole region - are led by Itau-Unibanco, recently created by the merger of the second and third strongest lenders. But an equally important function is played by smaller banks, which support smaller producers that would otherwise have no access to funding. This is true throughout the region.

"We're seeing clearly a bifurcation across industries, across market segments and across countries," says Mr Gallo. "The largest and best-established names that do have access again to international capital markets - so investment grade names in general - are not as affected by the liquidity crunch any more as second tier names are - names that do not have access to capital markets and have to rely only on the banking markets for their funding needs. These are the ones suffering the most, because banks overall are still tight with liquidity, are still healing from losses, and as a result have fewer resources available to spend on supporting their clients."

Bankers agree that the challenges in the local financial markets will continue, with a series of issues affecting not only the business world, but also the level of investment in Latin America's infrastructure development, where demand is very high and lenders' appetite is still extremely limited. The ability to finance trade flows offers a highly efficient use of capital and is key to economic recovery. This is why international and governmental funding commitment in this space is wide and established. And this is what many lenders are looking at.

"What this crisis taught us is that capital, or the use of capital, is going to be very relevant," says Mr Tapia. "We all know that financial markets have a very short memory but at least in the next two to three years, the whole of the banking system is going to be aware of trade finance instruments."