The skyline in Luanda seemingly never stops changing. Those who are away from the booming Angolan capital for more than a few weeks have become used to seeing the start of new skyscrapers, hotels or highways on their return.

More in this report

The frenzied activity in the city reflects what is happening in the wider economy. Since ending a devastating civil war in 2002, Angola has turned itself from a flailing economy with a gross domestic product (GDP) of less than $7bn to one with annual economic output of $110bn. Its economy is now the third biggest in sub-Saharan Africa, after South Africa and Nigeria, and more than twice the size of that of Ghana or Kenya.

Angola has huge offshore oil reserves to thank for its gains. The Portuguese-speaking country produces about 1.8 million barrels per day (bpd) of crude, most of it exported to China and the US.

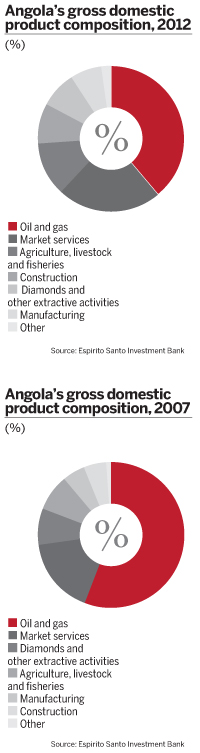

The commodity dominates the economy, accounting for 50% of overall output, 95% of export earnings and three-quarters of government revenues. That is unlikely to change much before the end of the decade, and perhaps even beyond then. David Thomson, an analyst at energy consultancy Wood Mackenzie, says that oil production, most of it coming from known reserves, could climb to 2.4 million or 2.5 million bpd by 2019.

From that point, it could rise even faster, should the most optimistic projections about Angola’s so-called 'pre-salt' reserves in ultra-deep water prove correct. The first major discovery of those was made early in 2012 by US firm Cobalt. How lucrative they become will depend on their quantity and on oil prices once they are on stream. But Mr Thomson believes they would be economically viable to drill at today’s prices.

“While it’s not the most straightforward of drilling, the technology and knowledge are improving all the time,” he says. “Three or four years ago, it was absolutely at the limit of what could be done. Now, while it’s not for every company, it is not by any means impossible.”

Vulnerability exposed

Regardless of whether crude production keeps going up, Angolan policy-makers realise the country is far too exposed to oil. They were made painfully aware of this when prices crashed in the second half of 2008 from $140 a barrel to just $40. Angola’s overheating economy went into freefall. Between 2008 and 2009, growth plummeted from 13% to barely more than zero, the currency depreciated heavily and the current account swung from a surplus of 8.5% of GDP to a deficit of 10%. The public finances were in tatters, with a fiscal surplus in 2008 turning in to a 7% deficit in 2009. Government arrears ballooned to more than $7bn.

It was clear that Angola’s buffers against external shocks were shoddy. Foreign exchange (FX) reserves had been inadequate to deal with the balance-of-payments crisis and the government had little grip on its expenditure due to carefree spending by ministries and the huge quasi-fiscal activities of state oil giant Sonangol not being accounted for properly.

“It’s very difficult for the government to implement fiscal policies when it doesn’t have a clear picture of what the numbers are,” says Nicholas Staines, the resident representative in Luanda of the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

The start of the clean-up came when the ruling Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola, or MPLA, signed a 27-month standby loan and adjustment programme with the IMF. Since then, plenty of macroeconomic reforms have been carried out. Spending was quickly brought under control (the government ran big fiscal surpluses in 2011 and 2012) and Sonangol’s activities on behalf of the state were incorporated into the budget for the first time earlier in 2013, greatly boosting fiscal transparency.

FX reserves were rebuilt, too. Having fallen to $14bn in 2009, they stood at an all-time high of $33bn at the end of 2012, equivalent to almost nine months of import cover. “That’s a substantial buffer and should help cushion against any further external shocks in the short to medium term,” says Gaimin Nonyane, an economist at Ecobank.

The government also managed to tame inflation, which had long blighted Angola. It fell from 15% in 2010 to less than 10% for the first time on record in August last year, which analysts say was no mean feat given the country’s still-feeble infrastructure and its need, owing to a lack of manufacturing, to import most finished goods. “Bringing inflation down to single digits was a huge challenge given the structural problems,” says Victor Lopes, a strategist at Standard Chartered.

New monetary tools

José Massano, governor of the Banco Nacional de Angola (BNA), the country's central bank, says that the government’s target is to reduce inflation to 7% by 2017. His confidence in achieving this stems, in part, from the new monetary instruments introduced under his tenure, which began in 2010. Before, the BNA had little way of influencing prices other than through keeping the exchange rate stable. But in 2011, a monetary policy committee, base interest rate and interbank rate were launched to give the authorities more ways to manage liquidity.

For now, the exchange rate probably remains the BNA’s single most important monetary tool, particularly given the interbank market’s illiquidity. But Mr Massano says that this will change in the coming years and that the extra instruments, together with a greater use of overnight repurchase agreements (repos) by the central bank, are leading to the establishment of market-based interest rates for the first time.

“In the past, commercial banks struggled to set interest rates,” he says. “Some would use inflation as a reference, some would use government securities, while others would use prudential regulations set by the BNA. It was very confusing. Now, most banks are using repo rates or the BNA’s base rate as a reference for loans.”

These moves are being implemented alongside attempts to de-dollarise an economy in which transactions and loans in the US currency are commonplace. Among the main measures is a new FX law for the hydrocarbon sector, which is currently being phased in and will lead to more payments to oil suppliers being made in kwanza. Mr Massano says that strengthening the local currency’s role in the economy is crucial if the BNA is to conduct its monetary duties effectively.

Analysts largely praise the efforts of policy-makers since 2009 and say their reforms have strengthened the Angolan economy, which with the GDP rising 8% in 2012 and on course for a similar outcome this year, is once again one of the world’s most buoyant. “Another collapse in oil prices would obviously have an impact, given the weight of oil on fiscal receipts and GDP,” says Mr Lopes. “But it probably wouldn’t be as bad as in 2008. At that time, the budget management and monetary policy were much less consistent than they are today.”

Diluting oil

The government still has plenty to do to address structural deficiencies in the economy. Widening its revenue base beyond the oil sector and cutting expensive fuel subsidies, even if that proves politically unpopular, are a must in the medium term, say most analysts. They add that without diversifying the economy from oil, the extraction of which provides few jobs for Angolans, the MPLA will struggle to create the levels of employment needed to reduce widespread poverty.

There have been improvements in the past five years, and much of the non-oil sector is thriving. Banks are highly profitable, while the country's breweries and telecommunications companies are among the most lucrative in Africa. Tiago Laranjeiro, head of Angola Capital Partners, which runs a private equity fund looking at firms involved in anything from fishing to advertising, says even small businesses are growing quickly. “If an Angolan company is competent and can serve its market, it will find customers,” he says.

Non-oil export earnings should be boosted later this year when a long-delayed $9bn liquefied natural gas terminal in the north of the country is expected to start operating. And a new mining code was ratified in late 2012, which officials hope will increase Angola’s already substantial output of diamonds and revive investment in its large reserves of other minerals, including iron ore and copper.

Further progress towards a more sophisticated economy will require heavy investments in infrastructure. Angola’s main roads, railways and ports are in a far better state today than after the civil war, thanks to billions of dollars-worth of public spending, much of it funded by oil-backed loans from China. But secondary roads generally remain dire, electricity supply is nowhere near sufficient to meet the needs of businesses and water shortages are frequent in the major cities.

“Angola’s infrastructure was entirely done away with during the civil war,” says Ricardo Soares de Oliveira, a politics lecturer at the University of Oxford in the UK. “No one should underestimate the seriousness of rectifying this. There could be a heavy infrastructure agenda for the next 25 years.”

The manufacturing and agricultural sectors suffer particularly badly. The latter has yet to recover its glory days under Portuguese rule, when the country was one of the world’s largest coffee and cotton producers. Today, its farming industry, hobbled by an inability to get produce to markets quickly and a lack of food processing businesses, is able to meet just half the national demand for food. “Resolving the infrastructural issues will go a long way to helping diversify the economy,” says Mr Staines of the IMF. “That’s when you’ll get the possibility of local producers competing with imports, especially in agriculture.”

Barriers to entry

More investment from abroad would also help. The vast majority of foreign direct investment goes to the oil industry. The MPLA is slowly opening up the rest of the economy. But the process of setting up a new business is often arduous and involves getting permission from the national agency for private investment, the BNA (which needs to approve the importation of capital) and the relevant ministry. Moreover, pressure is sometimes put on foreign-owned companies to give or sell stakes to opaque entities thought to be controlled by members of the ruling elite, a factor which puts off many would-be investors.

Bureaucracy and corruption are a large part of the reason Angola ranked 172 out of 185 countries in the World Bank’s latest Doing Business report, far below Nigeria and in equal place with Zimbabwe. “Angola is one of the strongest economies in Africa and it is full of potential and fast-growing business opportunities,” says Geoffrey White, chief executive of conglomerate Lonrho, which has several investments in the country. “[But] operating costs are high, it is a difficult business environment and there are significant challenges involved in getting set up from a bureaucracy perspective.”

Emerging market portfolio investors crave access to Angola. The country, rated BB- by Standard & Poor’s, issued a $1bn loan participation note (a similar instrument to a bond) in August last year, the yield on which tightened from 7% at launch to 3.6% in January thanks to heavy demand. And the government is considering a debut Eurobond in the coming 12 months.

Yet it remains difficult for outsiders to buy kwanza-denominated securities. Not only do strict capital controls exist, but there is no equity market and Angolan banks hoard virtually all the government bonds that are issued.

The launch of a stock exchange, which will be called the Bolsa de Valores e Derivados de Angola, has been constantly delayed since the 2009 crisis. Some bankers say there are scarcely any local firms with the auditing or governance standards needed to go public. But Anthony Lopes-Pinto, head of Imara Securities Angola, claims otherwise. “There are enough companies to list,” he says. “It’s political will that will decide when it happens. It is unfathomable that much smaller economies, such as Botswana, Malawi and Zimbabwe, can have deep, well-developed capital markets, while Angola, which boasts some of the largest banks, telecoms and beverages players in Africa, is deemed not ready.”

In the offing

For now, however, policy-makers seem more interested in establishing a proper bond market. The Capital Market Commission, the securities regulator, recently set out plans for a secondary debt market that would involve market makers, a government issuance calendar and more frequent sales of long-dated sovereign bonds.

Some investors, pointing to the buy-and-hold nature of bond markets in virtually all sub-Saharan countries other than South Africa, are sceptical a liquid market can be created.

Others disagree, saying the establishment of a regulated debt market will, in time, lead to a vibrant trading environment and the growth of Angola’s paltry insurance and pension industries. “This country must start with a debt market,” says Jorge Ramos, head of investment banking at Banco Espírito Santo Angola, a big local lender. “It will allow the government to finance itself with fair interest rates, allow the banks to distribute bonds to their clients and encourage the development of a trading mentality.”

Whether foreign investors will be allowed full access to that market depends on the government loosening exchange controls. It remains wary of hot money flows, lest they cause exchange rate volatility. Pedro Coelho, managing director of Standard Bank Angola, says that given the country’s history of high inflation, the authorities will likely maintain restrictions until they are confident that Angolans themselves would not rush to move money abroad. “The central bank [by keeping inflation stable] is trying to prove that people can trust the currency,” he says. “Then, they will slowly go ahead with the process of converting the kwanza into other currencies.”

Many local bankers cite Angola’s huge future infrastructure needs and say it will have no choice but to open its capital account. “It’s impossible for domestic banks or domestic savings to finance that,” says Mr Ramos. “They need to open up for international capital, [albeit with] some controls and supervision.”

Social focus

The MPLA is often criticised for focusing too little on social development and too much on large-scale capital projects. Analysts argue that oil riches and rapid economic growth are failing to benefit most Angolans. Despite a GDP per capita of about $6000, one of the highest in Africa, the country’s 20 million people largely languish in poverty. Life expectancy is just 51 and the infant mortality rate is one of the worst in the world.

The latest budget, approved in February, signalled a shift in emphasis, allocating a record level of funding to social sectors such as health and education. But boosting expenditure – which the government insists it will anyway carry out prudently given its experiences in 2009 – will not in itself be enough to curtail poverty. One oft-cited example is the vast Kilamba social housing complex outside Luanda. Built and funded by China to house 500,000 people, it lies mostly empty because few Angolans could afford the asking prices for flats.

Paul Collier, an economics professor at the University of Oxford, says that as well as failing to benefit the people it was meant for, the use of foreign labourers during its construction wasted an opportunity to provide locals with formal employment. “The challenge for any oil economy is to engage the population in the production process rather than just as recipients of consumption,” he says. “The Chinese are not good at that. Their forte is: ‘We build it and then we’ll hand it over.’ Their mode of operation is a bit ill-suited to what is needed.”

Angola’s economy may have been transformed in the past decade. But the country still has a long way to go before it has what can be classified as a modern, sophisticated economy. As Kilamba showed, achieving that will take more than just spending big sums of petrodollars. Tough reforms will be needed for years to come.