What happened?

At its monetary policy committee (MPC) meeting in late July, the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) surprised markets and bankers by increasing its cash reserve requirement (CRR) for public sector deposits – those made by the country’s federal, state and local governments – from 12% to 50%. The decision was dramatic, with analysts estimating that banks would have to place an extra N800bn ($5bn) to N1000bn in the CBN’s vaults.

Under its governor, Lamido Sanusi, the central bank had increased reserve requirements before, the last time being in July 2012 when they went up from 8% to 12% for all deposits. But nobody expected such a substantial move this time around.

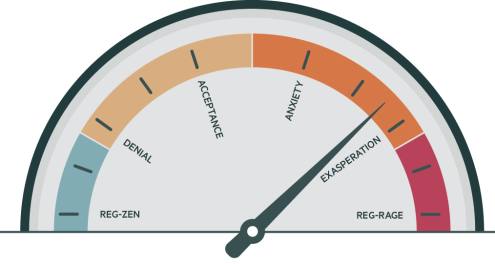

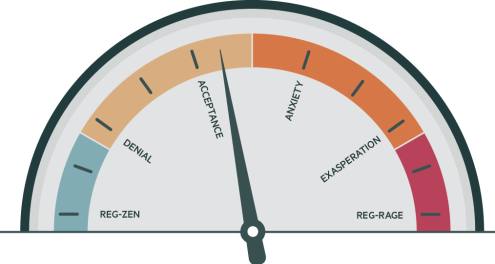

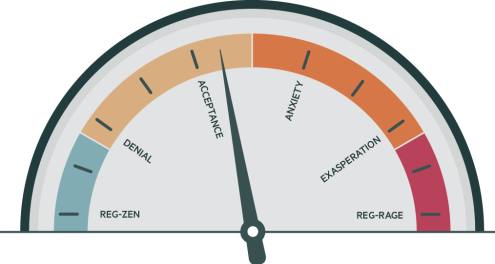

Markets reacted quickly. In the run up to August 7, when the new policy was enforced, three-month interbank rates soared by 850 basis points to 21.5%. The Lagos Stock Exchange also dipped on fears that the earnings of banks, which had been making substantial sums sourcing cheap public sector deposits and buying high-yield treasury bills with them, would suffer.

How did the banks react?

At first, not well. “We’ve had the banks screaming murder,” says Kingsley Moghalu, deputy governor of the CBN.

But in the two months since the central bank’s decision, bankers have calmed down. Most have been won over by Mr Sanusi’s argument that monetary policy needed to be tightened given that liquidity was rising and the naira was under pressure from May, when the US Federal Reserve first hinted that its huge monthly asset purchases would be slowed.

Aigboje Aig-Imoukhuede, head of Access Bank, one of Nigeria’s biggest lenders, who has made no secret of his desire to replace Mr Sanusi as governor when he steps down next year, said in early September that the CRR increase was necessary to save banks from a depreciating currency, something which has caused banking crises in Nigeria in the past.

Was there a longer term motive behind the CBN’s move?

Yes. The central bank’s strategy was innovative. While it raised the CRR for public deposits, it kept that for private sector deposits at 12%. Moreover, it did not change its base rate, which remained at 12% and which most analysts had thought it would use as its main tool at the July meeting.

It chose to use the CRR instead to address one of Mr Sanusi’s main bugbears: Nigerian banks routinely piling into the juicy treasury markets – where three-month treasury bills yield more than 11% – at the expense of private sector companies, which often struggle to access financing.

The governor has long lamented banks’ reliance on deposits from the public sector and the fact those deposits are often lent straight back to the government at a hefty return. Raising the CRR will ensure that happens less often, while keeping the base rate the same should mean that interest rates on loans do not rise substantially, despite the monetary tightening. “Hiking the CRR on public sector deposits deals with the source of the problem,” says Razia Khan, head of African research at Standard Chartered. “Rather than punishing the whole economy [by increasing the CRR across the board], it went for the problem at its source.”

Has it worked?

“It has certainly had a positive impact,” says Mr Moghalu. The deputy governor says only seven or eight banks were significantly affected by the new CRR, thus the spike in interbank rates in July did not damage the overall financial system. He adds that banks are already bolstering their efforts to mobilise deposits from the private sector. Part of their strategy involves increasing deposit rates, which is what the CBN wanted, since it felt savers in the country were getting a raw deal.

It is perhaps too early to assess the implications for liquidity and the naira. The currency initially rallied after the MPC’s announcement but then started to slide again, dropping 1.5% against the dollar between mid-August and mid-September.

What’s next?

The CBN finished its latest MPC meeting on September 24, as The Banker went to press. Analysts were not expecting any changes on the scale of the one in July. But Mr Moghalu does not rule out further rises in the public sector CRR or even the reserve requirements for other deposits. “The 12 members of the MPC will decide,” he says.

What seems certain, however, is that should there be any change in Nigeria’s liquidity levels or the position of the naira, the MPC will not take long to react.