The battle for supremacy in Latin America is now firmly under way and is set to be a fiercely fought contest between foreign and national players.

With its new-found stability combined with high growth rates, Latin America is one of the top investment destination regions in the world. Foreign banks such as Santander, BBVA and HSBC that have made major investments in the region over the past two decades are now reaping the rewards. Their position is further strengthened by the high price of Latin assets, which makes it difficult for competitors to follow.

However, these established players are not sitting as comfortably as they might have hoped a few years back, when it appeared that foreign banks would completely dominate Latin banking. Many national players have grown increasingly strong, helped by robust regulations that kept them safe throughout the global financial crisis. At the same time, some foreign banks such as UBS have retreated from the region. Latin national banks are now in a position to take on the foreigners both at home and, in some cases, in overseas markets as well.

In this complex chess game, finely tuned strategy is key. Moving quickly to exploit new opportunities is essential and the local arms of foreign banks cannot afford to allow head offices to sit on essential decisions. Finding the right staff is also a challenge as rapid growth has made critical skills both rare and expensive. The good news is that capital can now be raised locally on a large scale, as demonstrated spectacularly by Santander's $7bn Brazilian initial public offering last year.

Santander was one of the leading early movers in Latin America and the region now accounts for 48% of the group's profits. For Spanish rival BBVA the equivalent figure is 45%.

Eric Richard, co-head of the Europe, Middle East and Africa financial institutions group for investment banking at Credit Suisse - itself an early mover in Latin America through its 1998 purchase of Brazilian investment bank Garantia - says: "It has become very clear over the past couple of quarters that the momentum of the discussions that we are having with our clients over emerging markets has really picked up.

"Now that they feel slightly clearer on the regulatory environment [in Latin America], the banks we talk to in western Europe have started to refocus on where they're going to grow the business in the future, especially as the domestic market in many places presents a low-growth macroeconomic environment and a low-returns environment. The additional capital needed and additional regulatory constraints mean that the expected returns from the industry in those markets are going to be significantly lower than what we may have seen in the past."

Francisco Aristeguieta, head of Citi's global transaction services for Latin America and Mexico, says: "While in the past Latin America was the place to allocate assets you didn't know what to do with, the left-over pieces after having invested somewhere else, now the region is being seen more as [the destination for] a true asset-allocation strategy. That has changed as a result of the past two years' uncertainty in developed markets.

"In Latin America, you see [investment going to] the usual suspects such as Brazil and Mexico, but now investors also go more 'exotic' to destinations such as Peru, Colombia and Central America. This has become a solid trend that we are certainly picking up as a large custody and investor service provider in the region."

Citi itself is one of the longest-standing foreign banks in the region, having moved into Argentina in 1914, Brazil in 1915 and Colombia in 1929.

Challenges for Late arrivals

Coming late to the party has its challenges, especially in the more advanced Latin markets such as Brazil. Henrique Meirelles, governor of the Brazilian central bank and the former chief of the Brazilian operation of BankBoston (whose branches owner Banker of America swapped for a stake in Itaú in 2006), puts the matter very bluntly. "Foreign players always come [to Brazil], maybe open an office to look for opportunities, but they find none," he says.

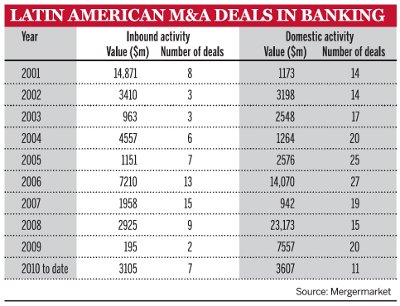

Apart from the lack of assets to buy in some Latin markets and the high price sought for those that are available, potential foreign buyers now find themselves in contention with domestic banks. Figures from Mergermarket - a mergers-and-acquisitions intelligence services owned by the Financial Times group - show eight foreign purchases in Latin America costing almost $15bn in 2001, while the total value of deals between regional lenders was a mere $1bn. This last figure comprises nearly twice as many deals as the foreign purchases, illustrating the small size of domestic Latin deals.

Now, however, the position has been reversed. From the particularly buoyant year of 2006 to the third quarter of 2010, there were 92 domestic deals within Latin America with a total value of more than $49bn. This was twice as many as the total number of acquisitions by foreign banks, while the domestic deals totalled three times the value of the foreign acquisitions.

Among the domestic bank deals was Itaú's ground-breaking $17.76bn acquisition of Unibanco in 2008, which created a regional giant that has the financial muscle to have wider international relevance. Itaú Unibanco has since gone from strength to strength and is now in a position to make its mark both regionally and internationally. The bank runs businesses in Argentina, Chile, Uruguay and Paraguay and last year there were rumours (false, as it turned out) that it was interested in buying Banamex, Citi's flagship operation in Mexico. The bank has always approached international expansion cautiously, however.

"Internationalisation is a very long journey and we need to consolidate our position in Brazil and gain skills in the markets in which we are already present," says Ricardo Marino, who is head of Itaú Unibanco's international businesses.

While it may be time for Itaú to consolidate, this has been an aggressive year for state-owned Banco do Brasil, which has taken a majority stake in Banco Patagonia of Argentina as well as expanding in the US to service Brazilian companies abroad, while continuing to grow at home with a series of Brazilian acquisitions in the past two years. These were the $1.9bn purchase of a 50% stake in Banco Votorantim, the $3bn acquisition of Banco Nossa Caixa and the earlier deals for state-government-owned Banco do Estado de Santa Caterina and the smaller Banco do Estado do Piaui.

Banco do Brasil's aggressive stance is something of a turnaround from the situation a few years back when only Brazil's private sector banks - Itaú Unibanco and Bradesco - were considered to be sufficiently trail-blazing to lead rather than follow market trends.

Francisco Aristeguieta of Citi says Latin America used to receive assets left over from investment elsewhere, but now attracts proper investment strategies in its own right

Buying abroad

Banks are not the only Latin American companies engaged in the overseas expansion trail. Companies such as Brazil-based steel producer Gerdau and petrochemical products manufacturer Braskem have spent $15bn this year buying overseas assets, while the recent $3.3bn acquisition of the US fast-food chain Burger King by a Brazilian-backed private equity firm reiterated the ambition and growing financial muscle of the country's businesses. Also earlier this year, Brazilian meatpacker Marfrig bought the US's Keystone Foods for $1.25bn, which means that the São Paulo-based company is now a key supplier to other US fast-food chains such as McDonald's and Subway. Companies from Brazil and most other Latin American countries have an advantage over some other foreign investors when buying into the US, as Latin groups do not face the same political opposition as Chinese state-owned companies and Middle Eastern sovereign wealth funds.

In Europe, the Brazilian development bank, Banco Nacional de Desenvolvimento Econômico e Social, opened a London office at the end of 2009, motivated by the growing appetite of Brazilian companies for European business deals.

Retreat by foreign banks

At the same time as Latin American companies have expanded abroad, so the crisis has seen some foreign companies retreating from the region. Beset with losses from US subprime mortgages, UBS was forced to pull back from Brazil. It first bought Brazilian investment bank Banco Pactual from shareholders including entrepreneur Andre Esteves for $3.1bn in 2006 and then sold it back to Mr Esteves' BTG Investments in 2009 for $2.5bn. For UBS, giving up a cherished foothold in Brazil that will be hard to regain is more significant than the financial losses on the Banco Pactual deal.

There are other less dramatic examples of foreign banks selling assets in the region. Santander sold its stake in Banco de Venezuela to the Venezuelan government in 2009 in response to a generally hostile political climate, in which nationalisation was a distinct possibility.

In July, GE Capital, the financial arm of US conglomerate General Electric, sold its Central American-based corporate bank and credit card group, BAC Credomatic, to a big regional banking group, Grupo Aval (owner of Banco de Bogota, Colombia's second largest bank) for $1.9bn, the largest foreign acquisition by a Colombian company. General Electric has been working on reducing the size of GE Capital for the past two years and has also sold its stake in Turkey's Garanti Bank and its Hong Kong consumer finance business.

In the less advanced countries of Latin America, foreign banks could still play a positive role in upgrading the banking system and any slowdown in their expansion there is regarded as negative by analysts.

Fernando Delgado, the International Monetary Fund's resident regional representative for Central America, says: "I see the internationalisation of the banking system [in the region] as unavoidable. But it will happen more slowly in Guatemala than in other Central American countries. It will not happen here any time soon."

Apart from divestments, major foreign players still committed to Central America are moving cautiously. In 2006, during an economic boom, Citigroup bought two large banks in the region (Banco Uno and Banco Cuscatlan) and HSBC bought Panama's Banistmo.

Scotiabank of Canada also acquired banks in Central America before the crisis, including a small operation in Guatemala. But there has been much less in the way of groundbreaking acquisitions since the onset of the crisis.

In investment banking, Latin banks are now competing strongly in what used to be a foreign preserve. Itaú Unibanco, Brazil's largest lender by tier 1 capital, has overtaken international giants Citi and Goldman Sachs in Brazilian bond underwriting and has become the fourth biggest manager of overseas bond sales from the Brazilian government and companies, according to data collected by Bloomberg. HSBC, Santander and JPMorgan were the only banks scoring better.

Cross-border consolidation

Consolidation across country borders is making Latin players and financial systems stronger. Colombia has engaged with Peru and Chile in a joint stock exchange project, which is being launched this month (November). Commercial trade between the three growing economies, which have a combined population of about 90 million, has risen noticeably, as has the level of investment between the countries.

"The joint stock exchange is going to grow critical mass, but it is also a symbolic act that demonstrates that investors in the three countries will work in the others as if it were one big country," says Vicente Rodero, BBVA's head in Latin America. "This will also help the three countries improve their structural deficits and their poverty levels."

BBVA has a strong presence across the region, with established businesses in Chile, Argentina and Peru. Brazil is one critical market where the bank has a gap, having sold its Brazilian operation to Bradesco in 2003 on the grounds that BBVA lacked sufficient market share to compete. "If we have a weakness, it is that our presence in Brazil is not what we would like it to be," says Mr Rodero. "Brazil is an engine for the region. It has very strong local banks that are expanding abroad, such as Itaú and Banco do Brasil. We're always looking for acquisition opportunities. If they arise, we'll be the first bank to look into it. The reality is that there isn't much on sale [in Brazil] and what's on sale has prices that are too high."

Yet some foreign banks are managing to make a successful entrance into Latin America. "The region continues to attract international banks," says Fernando Calloia, president of Banco de la República Oriental del Uruguay. "In the past year in particular, we have registered a greater aggressiveness in banks' strategies, with a consequent increase in competitiveness, mainly concerning retail banking and the high-quality loans business. Additionally, regional expansion has occurred through a sustained process of mergers and acquisitions."

In Uruguay, in addition to the purchase of ABN Amro's business by Banco Santander Uruguay in 2008, there has also been this year's acquisition of Crédit Agricole's operations by BBVA, which has resulted in the creation of two large competitors in the local banking system.

Detecting opportunities

Many others have detected opportunities in the region, whether in large or small economies. Swiss-based Sestante Capital is an investor in the 'Southern Cone' area (the southern part of South America) and sees various gaps in the market that it plans to fill by offering factoring, real-estate and corporate credit products in Uruguay.

"The banking system [in the region] is strict in its lending facilities for local corporations, so that fact determines that, given the economic boom in Latin America and the Caribbean, there exists an important market niche in corporate loans and capital market development," says Lorenzo Boldi, founder of Sestante Capital. "Local companies need capital to finance their growing businesses. Since capital market development [there] is at an early stage, banks need to position themselves to channel the needed capital."

Dublin-based Abbeyfield Group, a specialist in acquiring and operating financial services companies in Latin America, knows about the region's opportunities. It has successfully turned around the fate of Paraguay's Banco Sudameris since buying it six years ago. Banco Sudameris is now one of the fastest growing banks in the country and the first to issue long-term loans, taking advantage of a recently created government agency, the Agencia Financiera de Desarollo, which provides long-term financing to banks as a counterpart to their long-term lending to individuals and businesses.

Raising capital

Whereas channelling long-term finance to smaller regional companies is still a challenge in Latin America, the opportunity for large banks to raise capital locally has improved beyond all recognition in recent years. This is due to a combination of good regulation and deepening capital markets in the region. The result is a more stable financing structure.

"Latin America's reduced dependency on foreign banks' financing in foreign currency makes the region less vulnerable to the risk of repatriation of capital," says Enrique Iglesias, a former head of the Inter-American Development Bank and currently secretary-general of the Ibero-American Co-operation Secretariat, a new organisation set up to facilitate co-operation between Latin America, Spain and Portugal. "Further, the low dependency of subsidiaries of foreign banks on financing from the parent company limits their liquidity problems."

As Credit Suisse's Mr Richard says: "Banks have learned the hard way that finding capital and funding in as many places as possible is what you need to do when you're a big bank, because you never know which market is going to [become problematic] in the future."

The outlook in Latin America is for an ever-tougher fight between local and foreign banks for market share. But, increasingly, as all banks fund locally, hire locally and develop common expertise, the difference between foreign and domestic banks in Latin America will become more or less academic to the customer.