Two key legislative changes have had a significant impact on Canadian markets in the past couple of years. Combined, the removal of limits on ownership of foreign property in February 2005 and the ending of preferential tax treatments for so-called ‘income trust’ companies in October 2006 are dramatically altering the shape and make-up of Canada’s capital markets.

Income trusts

Between 2002 and 2006, the income trust model that had been introduced to benefit non-commercial and portfolio investment trusts was taken up with enthusiasm by large-scale public companies. By October last year, the market represented companies with more than C$200bn ($209bn) in market capitalisation. In 2006 alone, corporations representing almost C$70bn in market capitalisation had either converted themselves into income trusts (or publicly traded flow-through entities) or had announced plans to do so.

But by the middle of last year, the Canadian government decided that the subsequent tax losses were unacceptable and, in what is being called the “Halloween surprise”, the government quickly withdrew the advantageous tax treatment on October 31, 2006 as part of a broader tax reform programme. Any trusts created after that date will not benefit from previous tax treatments, and existing trusts will fall under a new tax regime from 2011.

“The government has given existing income trusts a safe harbour for new trust unit issues but the tax laws have yet to be finalised, leaving companies in a kind of limbo,” says Sarah Kavanagh, head of equity capital markets at Scotia Capital.

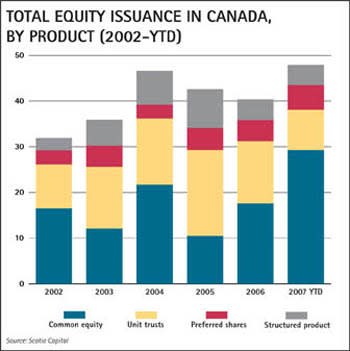

The effect has been dramatic. The steady growth in income trusts – from 98 in 2002 to 254 by October last year – has ceased. The only new trust initial public offering (IPO) this year was a real estate investment trust (REIT), and since October 31, 42 trusts have been acquired or taken private. Equity issuance from income trusts, down 41% on 2006 figures at C$8.5bn, is in the form of follow-ons from existing trusts.

“The government’s Halloween surprise meant that what had been driving the equity markets was suddenly shut down,” says Ms Kavanagh.

It is not all bad news for the equity capital market, however: common equity issuance is the strongest for five years (see graph below). Volumes are driven by mining, which represented 22% of all equity issuance and 38% of common stock issuance in the year to date. “This clearly reflects the run-up in prices of resource-based sectors over the past couple of years,” says Sante Corona, head of ECM at TD Securities.

“Resources have always driven Canadian markets but now they are completely dominant; commodity prices will continue to drive equity issuance volumes. If prices stay flat or rise then we will see a lot of [ECM] activity to fund acquisitions, the expansion of drilling programmes and the opening of mines,” he says.

The two largest deals early this year, both follow-ons, followed this trend, says Mr Corona. The first, a C$1.7bn bought deal for TransCanada, was to finance the acquisition of ANR Pipeline from El Paso, and the second, a C$1.1bn bought deal for utility Fortis, was to partly fund the acquisition of gas utility Terasen.

Ms Kavanagh agrees that although there is activity in other sectors – including reasonably healthy volumes in financial services, industrial products, healthcare and technology – mining and oil and gas are in the driving seat. She is also keenly aware that because virtually every sector has been motoring along happily, most companies are pretty cash rich. Therefore, equity issuance volumes are hostage to the fortune of mergers and acquisitions (M&A). “If the credit crisis continues or even gets worse, [M&A] could drastically slow down. And with less M&A, there would be fewer opportunities for equity raising. On the other hand, we may see more companies de-lever by raising equity,” she says.

A place for equity capital

With the market for income trusts effectively closed, there is one interesting question yet to be answered: where will all the equity capital go that is released by the leveraged buyout (LBO) of BCE? In June, BCE, Canada’s biggest telecoms company, agreed to be sold to the Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan and two US private equity houses, Providence Partners and Madison Dearborn Partners. At C$51.7bn, it is the largest LBO in the world and Canadian bankers say that, despite the turmoil in the credit markets, they are confident that the deal will be done.

“When the BCE deal closes, there will be C$40bn [the current equity ownership of BCE] looking [for assets] to buy. Previously, a lot of that would have gone into income trusts. So where will it go now? There aren’t many large cap companies with an investment profile similar to BCE in Canada for investors to buy,” says Ms Kavanagh.

One answer may be that it will go into foreign equity funds. In the third quarter of 2007 alone, C$263m flowed out of Canadian income trust equity, while C$881m flowed into global equity funds.

Ms Kavanagh says she thinks that trend will continue. “The ending of income trusts has combined with an earlier initiative, the removal of the foreign property limit, and this is pushing investment into offshore assets,” she says.

The ‘Maple’ market

The Canadian government’s removal of the foreign property limit on tax-deferred retirement plans and pension plans in February 2005 has also given a dramatic push to the levels of foreign issuance into the Canadian bond market, the Maple market. Between 1971 and 2004, there was about C$11.8bn of foreign debt placed in Canada. Between 2005 and 2007, volumes exploded, with more than C$56bn of issuance.

That is largely because of the development of the Maple market, according to Kevin Foley, global head of sales at Scotia Capital. “Before the legislative change in 2005, investors had only one option: to purchase foreign currency debt if they wanted to diversify away from domestic issuers,” says Mr Foley. “But, in practice, the lion’s share of the 30% foreign property cap went to foreign equities rather than debt.”

All that has changed. Since its inception, there have been more than 100 transactions with C$39.5bn of corporate issuance on the Maple market. By September, this year’s issuance totalling C$16bn had already surpassed total volumes in 2006 (although it still only comprises about 5% of the overall C$1000bn bond market).

Potential unleashed

It was the convergence of new foreign property rules (FPR) with several other trends that unleashed the market’s potential. In the past three years or so, Canadian investors’ desire to diversify their holdings has increased, alongside a huge growth in assets under management. Assets in mutual and pension funds alone have risen by more than C$600bn in five years, according to data from Statistics Canada. Meanwhile, government debt has declined by about C$49bn (the government is a net exporter of capital) while provincial and corporate debt has only risen by about C$150bn. Therefore, net new issuance – of about C$100bn – has been easily outpaced by the growth in assets under management looking for a home.

With sovereign supply dwindling, the government was forced to open up an alternative supply line for investors, and the removal of FPR ensured that all the ingredients were there to create a hearty appetite.

But it was the structural features of the Canadian market that allowed the market to take off, argues Mr Foley. Canada has an active interest rate swap and Canadian dollar-US dollar swap market, as well as a simple and speedy documentation process. The Toronto Stock Exchange has also developed a Universe + Maples index, and Maple bonds are now repo eligible. “It is these kinds of structural elements that enable a market to develop and mature,” says Mr Foley.

First movers

However, if investors are looking for diversification across issuers, geographies and sectors, only the first two requirements have been met; thus far, the market is dominated by financial institution (FI) issuance.

|

| “It was thought that the first movers would be non-financials, but it was the large US brokers and other FIs who quickly tapped the market,” says Chris Seip, managing director, debt capital markets, RBC Capital Markets. |

“Because FIs are high-quality credits, investors could digest new names [ie. buy paper from issuers new to them] very quickly and easily. But to see this market reach its full potential, we need to see it develop in terms of industrial, oil and gas names as well as financials. We need to see this market move down the credit curve,” he says.

Until now, however, corporates have not needed to raise much debt. “But capital budgets are on the increase, so we may see a growing need for corporates to raise capital,” says Mr Seip.

There may soon be some non-FI activity on the market. Rumours abound that the Abu Dhabi National Energy Company may be eyeing up the Maple market for an inaugural issue. Having recently spent about C$7.5bn on Canadian acquisitions (see article on page 30), it was taken on a four-day, non-deal related roadshow at the end of September by RBC.

Big deals

Three of the four biggest bond deals this year have been executed in the Canadian market. Morgan Stanley’s C$2.5bn multi-tranche (by tenor) bond in February, for example, was the largest corporate bond transaction in Canada and the largest Maple bond ever. It was also the largest single financing outside of the US.

And the market showed its depth in August when it soaked up the C$1.75bn of paper from GE Canada. “It got away C$1.75bn of paper at the most cost effective [rates possible] in August when, globally, markets were swooning,” says Mr Seip

The market is beginning to seem more and more like a mainstream market for global borrowers. “Issuers are increasingly realising that there is incredible scale and scope in the Canadian market, and that execution risk is minimised,” says Mr Seip. “We have a knowledgeable investor base, a curve that is well established and a relatively tight bid/offer spread relative to underlying [government bonds]. Dealers provide good liquidity in the after-market and there is relatively little need for marketing.”

Feeling the crunch

Like every other capital market, however, the Maple market has been tested during the credit crunch. There has been little new issuance since the crunch began in June. With everyone’s focus on liquidity, investors turned to liquid government paper (or, as is more likely considering the paucity of government issuance, Ontario paper) rather than hold Maple issues of up to C$300m.

“In the face of the crisis, Canadian investors have gone back to their knitting; they have retreated to what they know best,” says Andy McNair, managing director, DCM syndication, at TD Securities. “There have been some deals, such as Bank of America and the IFC, but the pace has slowed dramatically.”

Mr Foley believes that this is partly because of the nature of Canadian investors, who “are still getting used to trading in credits where the pricing is determined by factors outside of Canada”.

“The Maple market is dominated by global borrowers with global funding targets; Canadian investors have got to get used to the fact that [borrowers] are doing deals elsewhere that are subject to global volatility and repricing determined by how [the paper] trades elsewhere. Coupled with that, some of the major borrowers have underperformed the [defacto] Canadian benchmark, the Province of Ontario. This has helped to slow the market and lessen appetite,” says Mr Foley.

Mr McNair is relatively sanguine about the future of the market, however. He believes that appetite and necessity mean that activity will pick up in 2008. “The Canadian market has woken up to the fact that it needs to diversify and will be ever more prepared to do the work on foreign credits; and issuers have seen how formidable the Canadian market is in terms of its size and appetite for long tenors,” he says.

Looking at the debt markets as a whole, Mr Seip is also positive. In a downturn or in the face of liquidity problems, he argues that Canada will offer one of the most cost-effective markets in which to raise money. “Canadian investors are not fast money investors, they are largely buy and hold. They don’t see investments as a means to flip and therefore there isn’t the whippiness in Canada that has characterised some other markets.”

He cites recent transactions in the FIG space as an indication of the resilience and attractiveness of the Canadian market, such as TD Bank’s C$2.5bn subordinated debt deal in October. “Benchmark [size] transactions have been executed and were met with strong investor demand.”

Ending withholding tax

Mr Seip also believes that the competitiveness of Canadian capital markets has been further enhanced by another government-led development. On September 21, Canada and the US signed a new tax treaty that proposed that all withholding tax be ultimately removed from the Canadian capital markets system.

“Effectively, the withholding tax acts like a coupon clip for investors offshore; it particularly punishes them at the short end [of the curve],” says Mr Seip. “Once [the new treaty] is ratified, it will increase the options that Canadian domiciled issuers have when seeking short-term funding, in a similar way that the removal of foreign property rules opened up the Maple market for Canadian investors. This takes the hand-cuffs off Canadian issuers and allows them to diversify their short-term funding.”

But what are the implications for the domestic Canadian bond market? Of about C$65bn of issuance done in corporate format every year, Mr Seip says that about C$35bn is issued by subsidiaries of US companies. Will the new tax regime mean less issuance from them? “I don’t believe so,” says Mr Seip. “The same reasons that are driving the growth of Maple bonds will keep Canadian domiciled issuers here: the cost-effective Canadian market, the need for investor diversification by global issuers and the low execution risks in the Canadian market.”