Just as Mexico was recovering from the worst economic contraction in more than a decade, new worries over the country’s future came to the fore. The financial crisis and the economic troubles of the US – Mexico's main trading partner – hit the country in 2009, when it suffered a 6.1% contraction of gross domestic product (GDP), similar to the 6.2% contraction experienced in 1995 during the homegrown Tequila Crisis.

Editor's choice

The problems north of its border have forced authorities and international observers to reduce Mexico's economic expectations for this year and next year. While the country's government believes its economy will expand by 4% this year, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has revised downward its GDP growth forecast to 3.8% for 2011 and 3.6% for 2012. Economic research firm Roubini Global Economics has a more pessimistic view and expects a 3.7% GDP growth for 2011, down from the 4.3% it forecasted in June, and just 3% economic growth in 2012.

This is not surprising. Despite having started to diversify its trade away from the US, Mexico is still greatly influenced by its neighbour, with 80% of its exports still going to the US – it was 90% a decade ago. But despite these worries, Mexico still has much to feel positive about.

Growth story

At a press conference during the IMF/World Bank annual meetings in Washington, DC, in September, Mexico's newly appointed finance minister José Antonio Meade said: “Now Mexico has higher employment than it had at the highest moment prior to the [financial] crisis; it is growing and gaining market share in the US market; it is diversifying its exports to other countries; it is a country where industry [is recovering], the private sector is growing; [where there is] confidence in consumers and producers.”

Mexico is growing and gaining market share in the US market; it is diversifying its exports to other countries; it is a country where industry [is recovering], the private sector is growing

Mexican national statistics agency Inegi reported that the country's seasonally adjusted unemployment rate was 5.44% in August this year – a similar level to last year and less than the 5.9% peak of the summer of 2009. The US and many countries in the eurozone are currently suffering from unemployment rates of between 9% and 10%.

Mr Meade’s comments at the IMF/World Bank meeting are echoed by others. During the latest downturn, Mexico’s largest development bank, Nacional Financiera SNC (Nafinsa), had to ramp up its support to financing businesses, particularly in the small and medium-sized enterprises (SME) sector. The bank’s SME programme is now six times larger than it was five years ago and it has disbursed about $7bn in credit to smaller companies, says Hector Rangel, director of Nafinsa.

Mr Rangel also believes that Mexico is in a healthy state. “Despite what is happening [with the US and Europe], Mexico is in a very strong position, definitely the strongest it has been in my lifetime,” he says. “Public finances are in order, [there is an] autonomous central bank, large reserves – more than $140bn – a very large export-oriented economy, an open economy, low inflation, strong financial system, very well capitalised [banks].”

From hindrance to help

The banking system is indeed something Mexican bankers are proud of. While it fuelled the disastrous Tequila Crisis, exposing structural weaknesses and bad practices, the country’s banking system is now in good shape. Much attention has been paid to asset quality and capitalisation, with levels of Tier 1 capital averaging more than 14% and a capital-to-assets ratio of about 17% for the system.

The healthy condition of its lenders, coupled with the availability of funds through national and international development banks and a low level of financial services penetration, means that Mexico's banking sector could go beyond withstanding external economic shocks. Indeed, it may well be able to reduce the effects of such impacts on the country.

Mexico’s banking system is now one of the few in the world that today has the capacity to stimulate growth

“The Mexican banking system, more than being an obstacle or a drag on the growth economy [as in the past], will be an asset,” says Agustin Carstens, governor of Mexico’s central bank in an interview with The Banker at the IMF/World Bank meetings. “Mexico’s banking system is now one of the few in the world that today has the capacity to stimulate growth.”

Strong focus on the quality of assets also means that adopting Basel III’s international capital requirements rules will be relatively simple. “Mexico has a definition of capital that is now being promoted [internationally] with Basel III,” says Mr Carstens. “Mexico will probably be one of the first fully compliant countries on Basel III.”

Slow but solid

Because of the Tequila Crisis, financial intermediation in Mexico went down to extremely low levels. Loans to the private sector as a proportion of GDP went from 42% in 1994 and 1995 to 6% in 2003. Today they are about 20%. Mexico is the second largest economy in the Latin America region, yet compared with Chile or Brazil, with loans-to-GDP ratios of about 70% and 50%, respectively, Mexico’s banking activity looks small.

In Mexico we see the banking sector growing, while in other places in the world [in industrialised countries] it will have to shrink

“The pace of growth perhaps has been slower than what people might have wanted to see, but it has been solid,” says Alejandro Valenzuela, chief executive of Banorte, one of Mexico's largest banks. “You do not want to have a growth per se if it is fragile. Later on you will find yourself in trouble or in an even worse position than the one you started from. In Mexico we see the banking sector growing, while in other places in the world [in industrialised countries] it will have to shrink.”

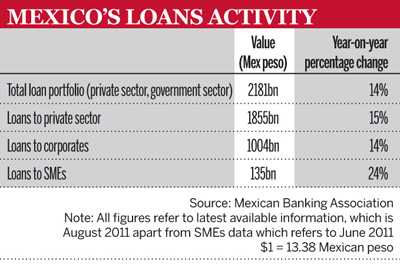

Bank financing to Mexico's private sector has maintained a positive trend over the past 12 months. As of August 2011, commercial banks’ credit to the private sector had increased by more than 14%, year on year, compared with a 6% annual growth for the same period in 2010. Loans to enterprises have been increasing at a rate of about 14%, consumer and credit card financing at 19.4% while mortgages are growing at a pace of close to 8%.

"Next year is going to be a challenging one – we are affected by the US’s conditions," says Javier Malagon, chief financial officer of BBVA Bancomer, Mexico's largest bank. "But total loans are still expected to grow above 10% in 2012; and this is thanks to the growth of internal demand. During the 2008 crisis, it was the growth of internal demand that absorbed external issues related to the US."

Targeting SMEs

Much still has to be done, however, to reach a wider number of Mexico's small businesses. According to development bank Nafinsa, about 95% of all businesses in the country are categorised as SMEs, and are responsible for generating about 70% of total employment and 50% of the GDP in Mexico.

Jaime Ruiz Sacristán, president of the Mexican Banks Association (MBA), says: “Banks are still lending, and there is demand for loans. [But] the main issue of Mexican banks, and of the economy, is the level of bancarisation.”

The challenge, as for all markets trying to extend their banking services to a wider client segment, is assessing risk for businesses that are not accustomed to formal reporting practices – or that do not quite operate in the formal economy – while making sure that asset quality does not deteriorate. Bad loans have been kept at bay so far. The current level of non-performing loans (NPLs) in the Mexican system is 2.7% of the total loan portfolio, with provisions that cover 180% of NPLs, according to the MBA.

Taking responsibility

“Product origination has to be as responsible as you can make it,” says Mr Valenzuela at Banorte. “[You have to] build the necessary relationship with your clients to really understand how they’re going through the business cycle.” Once smaller businesses realise that they will get cheaper financing with better terms if they get their house in order, they get into a positive loop, he says, adding: “Sharing our risk with the development bank [Nafinsa] helps, so that we can provide services to sectors that otherwise we would not be able to serve.”

Nafinsa is aware of the crucial role it plays in the development of Mexico's SMEs and among the new initiatives it is developing is a corporate credit card programme to cover up to 70% of the issuing bank’s risk. Nafinsa is also planning a scheme to guarantee up to 50% of the investment risk into medium-sized companies’ long-term bonds issued in the local market. While this provides a good opportunity for companies, it is also beneficial for banks. “The [large] corporate market is well served, so banks do not have many opportunities there anymore,” says Mr Rangel. “So the SME market is becoming a more interesting segment for them.”

International institutions are also getting involved in extending banking services to new customers. The World Bank’s International Finance Corporation (IFC) has recently signed an agreement with its second institution in the country, Banco del Bajio, and will back the lender when extending credit to exporters. Antonio Alves, the IFC’s senior regional head of short-term finance for Latin America, explains that thanks to the guarantee programme, Banco del Bajio will be in a position to support clients trading with markets the bank would not ordinarily feel comfortable taking risk on.

Reputational risk

Good macroeconomic indicators and a solid banking sector with good growth potential put Mexico in a strong position to withstand any external shocks. There is, however, an unsolved issue that is worrying some.

Although not openly discussed, some investors have expressed concerns on the drug wars that blight some cities in Mexico, and the potential reputational risk that the current situation may create when dealing with Mexican clients. From inside the country, the problem is acknowledged with different degrees of severity.

Mr Ruiz Sacristan of the MBA says that although painful, the impact of drug trafficking and related violence is localised to some areas and is not a widespread problem. “It has an important effect on some cities but it is not an issue that affects the whole of the country,” he says. “Industrial companies in those areas are suffering but banks still operate there; they have the same security measures that other branches have in other cities.”

Banorte’s Mr Valenzuela says that many multinationals are coming back to Mexico, despite the public security issues, but his view is not entirely optimistic: “Today we are in a difficult [position] because of drug trafficking. It is clearly affecting the economy, it is making people nervous, making people change their habits; you see shops being closed, you have to take additional measures at bank branches in the areas affected. But economic activity continues there, too.”

Others believe that the violence and higher profile that Mexico’s drug lords have generated is a result of stronger governmental efforts to fight them. However, this fight is far from being won. “There have been high-profile crimes, which insinuates that there is [a deeply rooted] problem; these things will not get solved quickly,” says one professional.

Mexico has defied many people's expectations by creating an environment in which its banking sector is both strong and stable. It is now to be hoped that it can take the same approach in tackling the drug trafficking problem that is potentially tarnishing the country's image in the eyes of international investors.