Superficially, the revival of US community banks flies in the face of the increase in standardised lending practices of the country’s biggest banks, and consumers’ reliance on digital tools for routine banking tasks. Nonetheless, the community banking model is thriving, especially in the urban areas of the US.

Additionally, one of the more surprising findings of a Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) survey of 1200 banks’ small business lending, published in October 2018, is that when making exceptions to loan policy, big US banks are just as likely to use a traditional high-touch and staff-intensive lending approach to generate and maintain small business clients as community banks, whose assets average about $1bn, or less than 0.1% the size of JPMorgan Chase, the US’s largest lender.

Acting small, thinking big

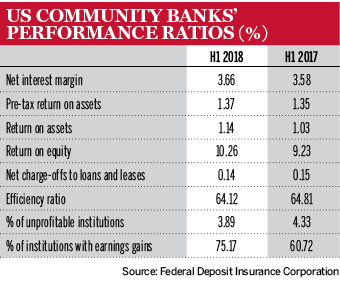

According to the FDIC, 5111 community banks reported an average 21.1% increase in profits in the second quarter of 2018 compared with the same three months in 2017, and the increase in community banks loans and leases in the 12 months to the end of June 2018 outpaced the banking industry as a whole by 3% (see table).

As of late October, seven new community banks had been incorporated in 2018, according to the Independent Community Bankers of America (ICBA), which lobbies for small banks. For the decade before that, not a single new community bank was created.

Meanwhile, existing community banks – many several decades old and family owned – have been adding new branches or acquiring them through mergers with other community banks. For example, Century Bank – one of the larger community banks in the US with assets of $4.8bn – now has 28 branches across eastern Massachusetts, up from 22 in 2008.

Century president and CEO Barry Sloane says: “Fundamentally, branches are still necessary for a community bank to grow because people need to see that you are substantive, stable and in their geography.

“Everybody loves the digital world until they have a problem and then they want to talk to a human being.”

Lloyd DeVaux, CEO of Miami-based Sunstate Bank, enhanced his bank’s market coverage and brand through the $29m all-cash acquisition of Intercontinental BankShares, another Miami community bank, resulting in a combined entity with more than $400m in assets, $325m in deposits and three branches. He says, in the light of current bank regulations, it is necessary to have “a little bit more size so as to be able to afford better technology, [achieve] better efficiencies and even hire a few specialists”. The merger will also enable Sunstate Bank to provide cash management services to small businesses, he adds.

Riding the recovery

ICBA group executive vice-president Paul Merski believes several factors underpin community banks’ recovery after several meagre post-crisis years. “They are benefiting from the significant tax cut [at the beginning of 2018], which will allow them to better serve their communities. The major regulatory relief bill [S2155] was also passed by Congress in May, which helps community banks in their mortgage lending by reducing regulations, as well as providing relief for exams and all kinds of reporting requirements,” he says.

“Interest rates are also rising and the yield curve has been steepening over the past year or so. Banks should be able to leverage that to get a little bit better net interest margin and get a better spread on their loans,” he adds.

On top of that, the growth in the wealth and financial resources of individuals and businesses on the back of a strong US economy is driving the profits in the financial sector. “There is absolutely no reason why community banks shouldn’t also get a larger piece of that growing wealth and income in the country and do well,” says Mr Merski.

Many community banks also have specialisations that fit in with their geographic area, which help them withstand economic swings. Century Bank, for example, combines traditional community bank activities, such as mortgages and home equity lending and small business lending, with institutional loans and services. Indeed, it has the largest portfolio of lending to not-for-profit organisations in Massachusetts, which is a state leader in universities and schools, as well as in healthcare and hospitals. “That’s been a marvellous segment for us. It has grown significantly and has very, very high quality credit,” says Mr Sloane.

For its part, Sunstate Bank serves local retail customers and small businesses but has also developed business relationships with Latin Americans in southern Florida and abroad. “A lot of foreigners come to Miami to buy a second home or to buy a rental home and that is our forte, to provide these properties in Florida for them. It has been a great business for us for the past 15 years,” says Mr DeVaux.

Urban resilience

The Community Bank of Wichita in Kansas, though a smaller bank with only one branch, is also doing well in the current economy, with a diversified revenue stream from small business and commercial real estate lending, and a portfolio of home mortgages. However, given that the economy is in the later stages of a prolonged expansion, its CEO and president Steve Carr, like other community bankers, is taking steps to mitigate the risks of a sharp rise in short-term interest rates or an inverted yield curve, which often precedes a downturn. For example, the bank originates long-term mortgages, but then it transfers them to an association, which does the underwriting and sells them off in the secondary market. “This takes us out of the interest rate risk factor,” says Mr Carr.

Community banks, which obtain most of their core deposits locally, have been resilient in the face of another challenge related to rising US interest rates too, which is the growing competition between US banks over deposits. Mr Carr says the Community Bank of Wichita still has a very high ratio of deposits to assets and excess funds to loan out. “We are not feeling a pinch at this point,” he adds.

However, one challenge that community banks face is the advent of new technology and changing customer behaviour, which is affecting them in two ways. First, many say they are losing home mortgage customers to new fintech players or non-banks, as more and more Americans feel comfortable applying for mortgages and mortgage products online.

Second, there is the difficulty of paying for new technology – whether this involves employing specialists to develop bespoke applications or acquiring off-the-shelf mobile banking and remote deposits apps, for example – at a time when a vast majority of people, especially the younger generation, wants or expects to have these services for free.

Small but critical

A key strength of community banks is that, although they represent only 18% of total US banking assets, they provide more than half of all small business lending, which is their traditional niche and speciality, according to the FDIC. For this reason, community banks are an indispensable component of the US economy. Small businesses are the US’s biggest employers – the sector creates the largest number of new jobs and is where most wage growth occurs.

The findings of the FDIC survey show there are several reasons why community banks are more successful at small business lending than big US banks and other competitors. A fundamental factor is that because community banks have specialised knowledge of their local community and customers, they therefore tend to base their credit decisions on local knowledge and non-standard data obtained through long-term relationships. As 'relationship' lenders, they approach small business lending in a more flexible and customised, case-by-case way, in contrast to large banks, which are more likely to use transactional and standardised lending methods.

Moreover, an important result of this approach is that less established firms or entrepreneurial/start-up companies – which may be unable to satisfy the requirements of the more structured approach to underwriting that larger banks use – are more likely to receive credit from a community bank.

In addition to these advantages, the FDIC survey found community banks are faster at providing loans to small businesses than large banks; more willing to accept non-standard collateral, such as real estate; and provide business clients with longer term loans, whether for accounts receivable, buying fixed assets and equipment, inventory or working capital. By contrast, large US banks tend to supply small businesses with shorter term lines of credit. They are much more likely to evaluate business credit scores and use standardised loan products as credit cards, as well as require minimum loan amounts.

The Community Bank of Wichita’s Mr Carr says: “Our bread and butter is the $250,000 to $300,000 loan customer. The large banks don’t really want to take care of a customer unless they are borrowing between $1m to $5m.”

Rural stakes

According to the FDIC, the survey was prompted by concern about the long-term trend of consolidation and decline in the number of small community banks because of the potential negative effects on US small business activity and formation.

The decline is most pronounced in rural America. According to a Wall Street Journal analysis, Community Reinvestment Act data in 2017 shows that the value of small loans to businesses in rural communities is now less than half what it was in 2004. Furthermore, out of the country’s total 1980 rural counties, 625 do not have a locally owned community bank, 115 are now served by just one branch, and 35 counties have no bank at all.

Rural community banks are in a category of their own. Estimates vary, but according to ICBA, rural community banks provide more than 80% of agricultural lending which, given that the US is the world’s third biggest food exporter, highlights these banks’ vital economic role.

But in 2018, rural community banks are under stress. For example, First Community Bank, based in Newell, Iowa, has four locations and is the only bank in three of them. It has $95m in assets and a $52m loan portfolio, most of it distributed to farmers, including a goat herder, hog farmers, and corn and soya bean farms – both crops have been hit by president Donald Trump’s trade war with China.

Gus Barker, executive vice-president of First Community Bank, emphasises that the agricultural sector has not been doing well in 2018, unlike the rest of the economy. “[It has been] a little bit of everything: droughts, trade wars, lower agricultural prices. Some of my farmers, just on the price of corn and soya beans, have lost $2m in annual income this year, while the cost of farm inputs has stayed the same,” he says.

A long-term challenge is the decline in the rural population. “Our customer base has been shrinking over the years. We’d like to see more young people come back and raise their families. [But] it gets difficult when jobs are scarce,” says Mr Barker.

According to Michael Martin, CEO of Western Bank, with $175m in assets and based in Lordsburg in the northwest corner of New Mexico – which is officially designated as 'frontier' land because of the scarcity of population per square mile – the biggest challenge facing rural community banks is attracting and retaining qualified employees.

Rising to the challenge

Opinions on why there are fewer rural banks tend to revolve around weak school systems, the financial crisis and the advent of large big-box retailers, which have hit local business activity and development.

However, rural banks are nothing if not resilient. Western Bank, for example, has a highly diversified loan portfolio: 40% is spread across livestock, alfalfa, cotton, corn, green chili and pecan and pistachio nut farms; 40% is distributed to small businesses, including small aircraft firms; and 20% is deployed in retail banking. There is also a trend of rural banks dropping a rural location and opening a branch in an urban area to ramp up their business. To offset the costs of keeping up with digital technology, many believe rural community banks will fund more loans and expand their market area from, say, a 50-kilometre radius to a 150-kilometre radius.

Despite the headwinds, there is widespread conviction that community banking is a good model for the rural US. Mr Martin says: “For farmers there are advantages to a community bank approach because they can obtain more variable and bespoke credit conditions. It is valuable to farmers to be able to sit down with their community banker a couple of times a year and explain what is going on with their business. Weather patterns change, crop prices change, inputs change – they need credit that can ride the cycles.”

Meanwhile, done well, urbanised community banking can be consistently profitable. According to Mr Sloane, Century Bank is in its eighth year of a record performance, growing organically at a rate of 8% to 9% annually in earnings, assets and capital, and it now has a return-on-equity ratio of about 12%, higher than the industry average. “It is one of the longest positive records of a New England bank, for sure,” he says.