When the Euro 2020 football tournament kicks off in June, the competition’s 5 billion-plus global viewing audience will be greeted by a new sponsor: Alipay. Under an eight-year agreement, the Chinese online and mobile payments behemoth will be the official global payments partner to all UEFA national team competitions.

Little known to Western consumers, Alipay is one of a handful of fintech giants that has revolutionised China’s financial services market over the past decade. But today, these tech titans are bringing this revolution to the rest of the world and, in doing so, are reshaping the global financial landscape.

To consider the implications, one need only look to China’s own experience. In just over a decade, at a time when the US was upgrading to chip-embedded bank cards, China has effectively morphed into a cashless economy. Its two dominant digital payments offerings, Alipay (owned by Ant Financial, an affiliate of Alibaba) and WeChat Pay (owned by Tencent), now account for 92% of the country’s $42,000bn annual mobile payments market, according to research from the Brookings Institution. This has been achieved through a user base of hundreds of millions, gained since Alipay launched its digital wallet offering in 2008, while that of WeChat Pay launched in 2011.

Serving consumers

“Rapid technology development in China’s financial services sector, particularly on the retail side, has happened because the country’s banks historically served state-owned enterprises and paid very little attention to households. Payment cards in China never developed to the same extent that they have in the West. Conversely, China’s fintech players have served consumers better and offered functionalities that have been well received by the market,” says Diego Zuluaga, a policy analyst at the Cato Institute’s Center for Monetary and Financial Alternatives.

By harnessing digital wallets and QR codes, both Alipay and WeChat Pay have achieved rapid growth across China. The result is a vast retail payments ecosystem, backed by the central bank, that not only offers merchants and consumers the ability to transact but also to access a countless number of functionalities from e-commerce to equity investments to interest-bearing accounts. For this reason, both products are known as ‘super apps’.

“The Chinese have been extremely innovative and they have transitioned almost all of their retail payments systems to mobile offerings with Alipay and WeChat Pay. So in these terms they are further ahead than the US and EU in terms of having ubiquitous, fast and cheap digital payments,” says Claudia Biancotti, a visiting fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics.

Domestic success has inevitably given rise to ambitions for international growth. Over the past two years in particular, WeChat Pay and Alipay have aggressively expanded their global network on the acquiring side, to expand merchant acceptance worldwide. For the most part, this strategy has been executed in markets that receive high numbers of Chinese tourists, including the US, western Europe and much of Asia.

“The rise of Chinese tourists is having an impact, with Alipay and WeChat Pay acceptance becoming highly important outside of China. As such, partnerships are becoming common with established Western payment processors to enable acceptance, which is giving Chinese vendors an inroad into the market,” says Nick Maynard, lead analyst with Juniper Research, a mobile, online and digital market research specialist.

Foreign partnerships

Numerous deals have been inked to that effect. In early 2019, Walgreens, a large US drugstore chain, agreed to deploy Alipay’s mobile payment platform across its stores nationwide. In 2018, London’s Camden Market asked its nearly 1000 shops and restaurants to begin accepting WeChat Pay mobile payments by signing up to the app. As a result, by 2019 Alipay was accepted in 55 countries, according to the company’s data, while various reports indicated that WeChat Pay was accepted in 49. (Neither entity responded to requests for comment for this article.)

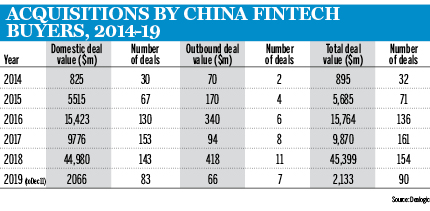

More recently, however, Chinese fintech groups, including Alipay and WeChat Pay, have been making strides beyond serving Chinese tourists, a dynamic that is likely to continue. In February 2019, Ant Financial, the parent company of Alipay, agreed a $700m deal to acquire UK payments group WorldFirst. The deal is considered to be a major boost for the company’s global ambitions.

“That acquisition is a bit more substantial because [Ant Financial] gets into the position of having a payments licence and that allows it to do a lot more,” says Zennon Kapron, director of Kapronasia, a fintech market research and consulting firm based in Singapore. “The WorldFirst footprint gives it a lot more flexibility and breadth in terms of the products and services that it can bring to market. So off the back of that, it effectively allows [Alipay] to do cross-border payments in Europe and globally and potentially set up its own digital wallet in other markets as well.”

In a November 2019 interview with CNBC, Douglas Feagin, president of the international business group of Ant Financial, revealed the company’s ambitions to serve 2 billion customers around the world over the next decade, up from 1.2 billion today. As part of this growth, it plans to significantly ramp up its international user base. But for China’s tech giants to realise these plans, they are more likely to turn to emerging markets because, in some ways, a natural synergy exists between their digital payment offerings and these economies.

“From an emerging market perspective, China provides something of an example to follow in terms of economic development. And when it comes to China's payments technology and payments systems, emerging markets also see something that is easy to adopt, since it comes from a country that not long ago was at a similar development stage as these other countries, with low bank penetration but high phone use,” says the Cato Institute’s Mr Zuluaga.

Belt and Road ambitions

This point is relevant because it aligns with many markets along China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) that lack legacy financial infrastructure. And as Chinese public and private sector engagement with these economies expands, so too will the scope for its fintech giants to gain a foothold, principally across Asia, Africa and the Middle East.

“This lack of legacy issues is relevant to BRI countries. For fintech companies operating in some of these markets, for example, Chinese payments offerings are much more relevant than US or European counterparts. I think China has an edge in emerging markets,” says Jennifer Zhu Scott, a dual fellow with the Asia-Pacific programme and Digital Society Initiative at non-governmental organisation Chatham House.

UnionPay, China's state-controlled payment card issuer, has been deploying its payment technology along the Belt and Road for some time. Though it is better known in China for card issuance, the company has also been working on mobile payments technology further afield. In the United Arab Emirates, for instance, UnionPay International signed an August 2019 agreement with sharia-compliant financial institution Noor Bank to provide QR-based mobile payment services. Meanwhile, in July it became the first international group to be granted a payment systems operator licence by Nepal’s central bank. As such, UnionPay’s QR code offering has become the first legal cross-border QR payment solution in the country.

“QR codes in particular are highly suitable for other markets for the same reasons they work in China: no requirement for fixed point-of-sale infrastructure, low cost to merchants, easy use via smartphones. As such, particularly in emerging markets, these payments have high potential,” says Mr Maynard.

New networks

As a result of the investments being made by China’s tech giants, new Chinese-backed payments networks, and their associated ecosystems, are beginning to flourish in parts of the world that most need financial services. The scale, expertise and resources that can be offered by China’s tech giants are permitting smaller, localised digital wallets the opportunity to increase their ambitions and offer cross-border functionality and interoperability with peers in other markets. All of this is being achieved off the back of Chinese investment and know-how.

“[China’s fintech giants] are working to establish this global network. In theory, you could send money between different digital wallets, across borders, that were under the umbrella of the same Chinese fintech group,” says Mr Kapron. “For a domestic digital payments provider in a smaller market, offering cross-border payments into the US or Europe, for example, would be challenging. But with a large, Chinese tech group operating in the back end and taking a couple of basis points off of each transaction, it becomes feasible.”

But the fact that these developments are taking place against a backdrop of a technology cold war between the US and China means that, for some, they come loaded with a strategic dimension. Writing in 2019, the economic historian Niall Ferguson warned that the huge advancements being made by Chinese fintech groups, globally, were placing US power “on a financial knife-edge”. Noting that the “country that leads in financial innovation leads in every way”, Mr Ferguson indicated that, in relative terms, the US has paid too much attention to telecommunications and not enough on maintaining its monetary and financial leadership.

State-backed digital currency?

The potential launch of a Chinese state-backed digital currency has generated further discussions in this domain because it appears to be closely linked to China’s fintech giants, and in particular WeChat Pay and Alipay.

“The single most interesting development in my view is the People’s Bank of China [PBOC] digital currency. This could have significant geopolitical implications. China has been, for a long time, trying to reconcile the competing demands of capital controls with the desire to internationalise its currency. With the traditional monetary system, it is very difficult to balance these competing needs,” says Ms Zhu Scott.

After five years of research by a team at the PBOC, China is on the verge of becoming the first country in the world to launch a digital currency. Though much remains unclear regarding the mechanics behind the currency, or indeed how it will be rolled out, some observers expect a launch to occur in the near future.

“Personally, I wouldn’t be surprised if the end game was getting the existing platforms of Alipay and WeChat Pay to integrate with the central bank digital currency. It wouldn’t make any sense for the PBOC to develop a digital currency and then to decide not to deploy it everywhere,” says Ms Biancotti.

For some emerging markets along the BRI, where there is a strong presence of Chinese fintech providers and their associated payments systems, and where heavy infrastructure investment is taking place, the arrival of a state-backed digital currency would help to internationalise the renminbi while enhancing its attractiveness as a currency for trading and settlement.

“If you look at the Belt and Road, most of the large infrastructure projects are all pretty much done by Chinese companies. So would it be easier for them to just directly trade with China’s currency, or for both sides to use their US dollar reserves and trade with each other and exchange through the local currency? The transaction cost differential is very obvious,” says Ms Zhu Scott.

According to Ms Zhu Scott, the nature of Alipay and WeChat Pay’s payments proposition means that any shift to a digital currency would be easy enough for the two groups to shoulder. In addition, as of 2018, China’s two digital payments giants were required to settle and clear all transactions through a PBOC-based clearing house. “There shouldn’t be too much of a direct implication for those companies. Basically, Alipay and WeChat Pay use traditional renminbi and their existing infrastructure to digitalise the ledger. So they are using this digital infrastructure to run an enormous national ledger. For those two companies to adopt a digital currency will not be a significant shift,” says Ms Zhu Scott.

Implications for the dollar

This outlook is generating concern in some policy-making circles, not least because it has the potential to diminish the role of the US dollar and US financial networks in the global economy. “[It is very] meaningful for China and the global economy if China’s development includes the expanding reach of its financial services and the internationalisation of its currency across the BRI countries,” says Elizabeth Rosenberg, senior fellow and director of the energy, economics and security programme at the Centre for a New American Security, a bipartisan think tank in Washington, DC.

“It is about scale. If you can achieve sufficient scale so you can manage real liquidity, payments and the clearing of those payments within your ecosystem, then think about what you can do outside of the reach of financial regulation coming from Washington or European capitals. This includes requirements for financial stability, anti-money laundering/countering financing of terrorism regulations, all of it.”

Despite the speculation around China’s digital currency, and the ways in which it will interact with its fintech giants, obvious conclusions are still difficult to draw. For one, China’s digital payments networks have already created a compelling standalone proposition that effectively acts as a digital currency, according to Martin Chorzempa, a research fellow at the Peterson Institute. “I have a hard time imagining how this would be much more desired than using existing Alipay and WeChat Pay tools. All of the money that is stored in these wallets, or is in transit, is deposited at the central bank and 100% reserve backed so it is already in some way a type of central bank digital currency,” he says.

Irrespective of how this plays out, China’s fintech giants are leaving their mark. Through a mix of innovation, customer-centric offerings and the ability to offer scale and interoperability within and between markets, many parts of the world are likely to benefit from and be shaped by financial technology developed in China.

“What is happening is a paradigm shift from traditional financial infrastructure to digital infrastructure and Chinese companies are leading the way,” says Ms Zhu Scott.