While economists worry about oil prices hitting $100 and cheap textiles from China flooding the world, far-sighted bankers are looking at the financial opportunities. Foreign exchange (FX) reserves are piling up in China and the Gulf’s oil exporting countries in quantities never before seen in history. By end 2006 the estimated combined reserves of the Gulf Co-operation Council (GCC) states and China will already have reached a massive $1350bn. That is the equivalent of the current reserves of the 24 largest economies in Asia, Latin America, central Europe (including Russia) and Africa combined.

They cannot all be channelled into US treasury bonds. Even debt-hungry America does not have that kind of appetite to borrow money and the Gulf states have been wary of placing their funds in the US since 9/11.

The race is on to find new and interesting ways to help these nouveaux riches nations spend their money, hopefully wisely. The best solutions help the cause of domestic development by keeping valuable funds at home. They can then be used to finance infrastructure projects that ensure future growth and a rising standard of living. For bankers these outcomes provide rich pickings in everything from project finance to asset management.

The worst result is when new-found wealth is wasted in consumption and subsidy and a country stagnates, as happened in Nigeria. The Gulf states and China must take care to avoid that kind of mistake.

Even before they get to the happy stage of spending their new monies, there is a possible spoiling factor to be considered. If the oil price got too outlandish too quickly, energy costs could derail China’s economy in mid-stream.

Assuming that does not happen, with labour costs that are massively below anywhere else on the planet, China should be able to absorb steady rises without too much pain. Chinese textile exports to the US, for example, reached a massive $5.9bn in the first five months of 2005, 85% up on last year. It is small wonder that China’s gross reserves are expected to hit $742bn this year, $851bn next year and $1310bn by the end of 2012, according to Oxford Economic Forecasting. That is the equivalent to the current GDP of Belgium and Spain added together.

How China’s reserves have grown

This rapid growth in China’s reserves is a recent phenomenon. At the start of China’s reform era, FX reserves were minimal, dropping to $1.6bn at the end of 1978 but enough to cover a very small import bill. By 1987, a small trade surplus plus comfortable net capital inflows pushed reserves up to $16.3bn. In the 1990s, trade and current accounts were in deficit but the acceleration of inward foreign direct investment (FDI) flows kept reserves rising, reaching $165.6bn at end 2000.

The big surge came after joining the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001, when both imports and exports accelerated at a fast pace and FDI inflows exceeded $50bn a year between 2002-2003. From $212bn at the end of 2001, FX reserves grew rapidly, rising by more than $200bn in 2004 to reach $610bn at year-end and a record $711bn at the end of June 2005. China boosted its reserves by $324bn in the two years from 2003 to end-2004 and has increased them by $425bn over the latest 30-month period.

With the country now viewed by some as one of the twin engines of the global economy (along with the US), and a dominant manufacturing force for the world, a key issue is going to be how it uses its financial muscle. Although, in 2004, China still only represented 4% of global GDP (compared with the US’s 28% and Japan’s 12%), its export capacity and potential give it enormous clout and, like the Gulf oil economies, bring with it enormous FX reserves.

New wealth experience

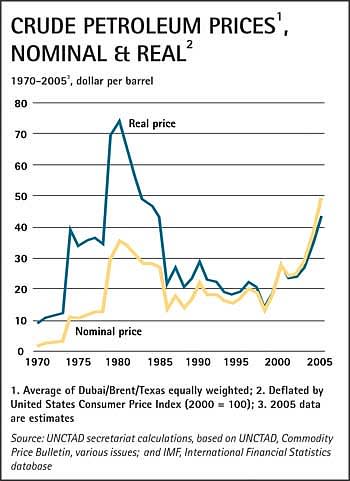

Although the wealth effect is new to China, the Gulf states have been there before. After the 1970s’ oil price hikes, the arrival of the petrodollar was of huge macroeconomic importance but many mistakes were made. High oil prices caused global stagflation and over-liquid banks lent too freely in Latin America, ushering in the debt crisis of the 1980s. The turmoil caused in the global economy hurt the oil exporters as much as anyone else and they have since learned to be moderate in delivering oil price increases.

This time, bankers and investors need to think smarter and, after the leaner times of the 1990s, there is also a case for keeping Gulf wealth at home. With oil prices breaking through $70, there is little doubt about how much the regional economy is set to grow.

“The GCC is in the midst of a period of exceptional economic performance,” says Charles Dallara, MD of the Institute of International Finance (IIF), the Washington-based think tank. “We are now forecasting aggregate GDP to expand by more than one third for 2005 and 2006, while foreign assets are estimated to rise in these two years by more than $360bn.”

Aggregate GCC exports are forecast to be $391bn in 2005 and $416bn in 2006, according to IIF estimates, aggregates that are similar to the combined total for Brazil, India and Russia, the three largest developing economies in the world besides China.

The IIF forecasts that the GCC will add $363bn to its foreign assets in 2005 and 2006, and that is based on the relatively conservative price of Brent crude per barrel (p/b) averaging $54 this year and $55 next year.

Estimating the foreign assets of the GCC states (Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates) is an inexact science because figures are not formally disclosed. But Samba, Saudi Arabia’s second largest bank, forecast recently that the kingdom’s foreign assets would grow by $47bn in 2005 to reach $135bn at year-end. So it is likely that GCC foreign reserves, built on increasing oil prices, could stretch well beyond $500bn at the end of next year.

For both China and the GCC states, a lot of the short-term attention is focused on trade – and rightly so – but the critical factor in the longer term is how the funds are used. This is important not only for the countries directly concerned but also for their overall global financial impact.

Assuming in the medium to longer term that China’s expansion will continue at a conservative growth rate of 8% or more and oil prices remain well above $55 p/b, what should China and the GCC do with their burgeoning reserves? On the estimates above, the FX reserves of China and the GCC combined will amount at the end of 2006 to a massive $1350bn or more.

China’s money moves west

What is the financial world doing about this $1350bn? In recent years China has used its reserves to buy US treasuries and plug President George W Bush’s administration’s burgeoning budget deficit. “For China, US treasuries are very attractive assets with which to back up the country’s weak banking system” says Wall Street analyst Henry Kaufman.

China has spent a reported 70% of its reserves on US paper in recent years, amounting to more than $450bn, but will Beijing continue to prop up US deficits and who will fill the gap if it does not buy? This year, China has begun to diversify and also sought to buy other foreign assets, such as its $18.5bn bid for US energy giant Unocal, which has created increasing fear among US politicians. As the US trade deficit rises above 6% of GDP, both the US and China need to decide how to deal with this reserves conundrum.

“The goal China should pursue is the betterment of the lives of its people, and this can only be achieved through institutional reforms and by investing in domestic human capital and physical capital, such as production facilities and infrastructure,” says Chinese commentator Chi Hung Kwan. “The government should stop lending the precious savings of its people to the US government at low interest and instead use it more efficiently to develop the economy.”

Social reconstruction fund

University of California professor Deepak Lal also acknowledges the absurdity of a relatively capital-poor developing country making such large, unrequited transfers to a rich country. He suggests another way for China to use its huge reserves: “Say only $100bn is needed to fend off any speculative attack, the rest (some $500bn) as well as any future accruals could be put into a social reconstruction fund under the central bank. This would function like any other big pension fund, such as that for the World Bank, whose annual return averaged over 10 years has been about 8%.”

According to Mr Lal, a so-called China social reconstruction fund based on the above could produce an annual return of $40bn or more, which could be used to cover the state-owned enterprises’ social burdens. These enterprises could then be treated as normal entities, to be privatised if viable and closed down if not.

The fund could help to balance out some of China’s conflicting financial factors, such as a 40% savings rate, large state-owned banks stuffed with non-performing loans to state-owned enterprises and inefficient financial markets. An active fund could help to revitalise the banking sector and also be used to focus on the country’s national project: developing western China.

As Chinese finance minister Jin Renqing explained to The Banker, the development of western China is a key priority and necessary if the strategy of moving 240 million people off the land into cities and more productive employment is to be successful.

Leading economist Adam Smith pointed out that “the wealth of a nation is the amount it can regularly consume”. Scottish financial consultant Catherine Smith says that although China has considerable reserves, these do not represent the amount “it can regularly consume” because its potential consumption is limited not by money but by infrastructure. “The purchasing power of China will generate the future wealth of China only if that infrastructure is developed in advance of the consumption that it enables,” she says. Therefore, a reconstruction fund, with a focus on infrastructure, could be a much more fulfilling use of China’s reserves than low yielding US paper.

Gulf states face hostility

Similarly, the GCC states have suffered a certain degree of hostility towards their investment activities abroad, particularly since 9/11, and are considering growing opportunities at home. With improved infrastructure, such as Saudi Arabia’s recent Capital Markets Law, the domestic investment horizon is opening up in the Gulf but more is needed.

Despite huge oil wealth, the top 50 GCC banks’ combined Tier 1 capital only amounts to $42.8bn – slightly less than that of Royal Bank of Scotland. The Gulf for various reasons has not produced significant financial institutions, and the bulk of GCC funds have been invested abroad with varying degrees of success. Perhaps the latest oil revenue surge and reserves glut could, as in China, stimulate the creation of a GCC reconstruction fund that could not only meet local project finance needs, but also address major regional issues in, for example, Iraq and Africa.

Although many development funds set up on the back of oil booms in the 1970s and 1980s have failed to excite, and GCC banks have been profitable but remain small, the prospect of $500bn plus in reserves at the end of 2006 could inspire something new. A large GCC fund, designed along World Bank lines and incorporating the world’s best financial expertise, could give the Gulf states some focused financial muscle to match their oil clout. The GCC states can and should make better use of their financial resources in a region that is crying out for funds and development.

Expertise is needed in China

Leading Western banks have recently been buying into the large Chinese banks but it is not Western capital but Western expertise that is needed. China and the Gulf are ripe for a huge injection of financial engineering in whatever form is possible.

For both China and the GCC, buying US treasuries and placing funds abroad have been the preferred options to date in managing their FX reserves. With combined reserves estimated at $1350bn by the end of next year, though, new strategies are needed to provide better value at home.

Reconstruction funds can be part of those strategies; both China and the GCC need to make better domestic use of their wealth, and the rest of the world, particularly the US, needs to adapt to this new reality. These are large tasks ahead. THE GULF’S FINANCIAL MUSCLE

- GCC exports, estimated at $391bn in 2005, are similar to the combined total for Brazil, India and Russia

- Saudi Arabia’s oil export revenue between 2004 and 2006 is set to be greater than for the whole of the 1990s

- The GCC holds 45% of the world’s oil reserves and supplies 20% of global crude production

CHINA’S FINANCIAL MUSCLE

- Reserves of $711bn in June 2005 are forecast to rise to $1310bn in 2012, the current size of Spain and Belgium combined

- China’s passenger car market is expected to reach three million in 2005 and 15.8% of world output by 2012

- China is the world’s biggest mobile phone market with 350 million subscribers and is expected to reach almost 600 million in 2009