When Tonga was hit by Cyclone Gita in February 2018, it damaged 1100 houses, leaving 120 destroyed. The 230 kilometre-per-hour winds also destroyed part of the country’s historic parliament building. The storm caused $210m-worth of damage, equivalent to almost one-third of Tonga’s gross domestic product (GDP).

In the following weeks, there was a global response to help rebuild the country. Donations poured in from across the international community. The Asian Development Bank (ADB) came forward with $6m to fund early recovery activities. New Zealand pledged NZ$750,000 ($508,000) and its defence forces, if needed. China also stepped forward with $1.3m in emergency financing.

Tonga had received support from China before, and at a time when additional foreign support had not been so forthcoming. Following political riots in 2006 that badly damaged the capital city of Nuku'alofa, Export-Import Bank of China (EximBank) provided loans in 2008 and 2010 totalling $160m to fund the rebuilding programme. However, in August 2018, as the time approached for the repayments to begin, Tongan prime minister 'Akilisi Pōhiva called for the Pacific Islands to band together to ask Beijing to cancel their debts.

The demands were short lived. The call to drop the debt was withdrawn a day later, allegedly after complaints from Beijing. In a statement released by the Tonga's Ministry of Information and Communications, Mr Pōhiva backtracked and instead outlined the role China had played in helping Tonga to recover from the riots, stating: “The Tongan government had sought help for reconstruction from many countries and China was the only country that was willing to provide a concessional loan on a large scale.” It was later announced Beijing had granted Tonga a five-year reprieve on the debt repayment.

Expanding the belt

Stories such as this fuel the Western view of Chinese investment in the region that the funds are being provided at high interest rates, or that China is using its financial power to strategically extend its influence across the South Pacific. Indeed, the region has seen an increase in the amount of support received from China. But, as with the rebuilding programme after the riots in Tonga, in some cases it has been vital because no other financing has been forthcoming.

In the Cook Islands there is a belief that Chinese engagement in the region has been positive as a whole. Mark Brown, deputy prime minister of the Cook Islands, says: “[The] Belt and Road [Initiative – BRI] has provided the Cook Islands with good investments. Working with China has opened up links for trade and given greater access to the [Chinese] market.”

Mr Brown has previously spoken about how investment from China has helped to build infrastructure in the Cook Islands that was not supported by other development partners. He also hopes the involvement of China will encourage other countries to invest.

“Our experience of working with Chinese investors is they are engaged with the delivery of projects and have been flexible in adapting to our requirements,” adds Mr Brown.

The collaboration between the two countries looks set to continue. In November 2018 it was announced that China would provide the Cook Islands with a $10m loan as part of an economic and technical co-operation agreement.

Mr Brown believes co-operation with China is about taking the money that is available, and when it is needed. “The island centres already have significant debt with the multilateral agencies, but cannot rely on them in all circumstances,” he says. “Tonga has 60% of its GDP in debt, but only the Chinese provided funding when it needed to rebuild its capital following the riots. Taking Chinese debt was the only option.”

A need for speed

The reason the Pacific Island countries are often choosing to work with Chinese investors is their swift reaction time. Martin St Hilaire, resident director of Vanuatu-based Pacific Private Bank, says: “China is quick to move and provide support. The view in the Pacific Islands goes against the Western idea. The Chinese are not seen as being a bad influence. They are building infrastructure and hotels.”

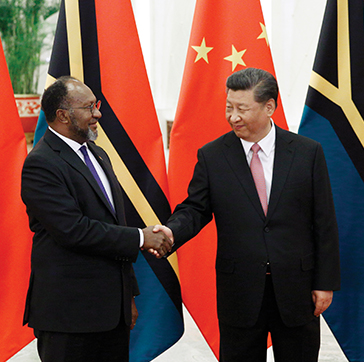

While individual countries are establishing ties with China, taking a regional approach to working with Beijing has been touted. At present, eight Pacific Island nations have signed memorandums of understanding with China as part of the BRI. During a speech in February 2019, Dame Meg Taylor, secretary-general of the regional political and economic policy organisation Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat, outlined the group’s position on China, including taking a regional approach to working with Beijing. She also rejected the framing of it being a dilemma between choosing China or traditional financing partners. “Such a narrative tends to portray the nations of the Pacific as passive collaborators or victims of a new wave of colonialism,” she said.

Ms Taylor added that the influence of China brings both direct financing, and the benefit of creating greater competition, noting that the region has seen some of its existing financial supporters “resetting their priorities and stepping up engagement in the Pacific. We are also seeing some new partners emerging, as well as the return of partners who had long left the region.” Greater co-operation with China can provide access to markets, technology and financing, infrastructure that the Pacific Islands nations had felt excluded from, she added.

Debt dilemmas

Gaining this support does come at a cost. While there are worries about the levels of debt these nations now owe to China, they are not the only loans they have to repay. Caleb Jarvis, trade and investment commissioner of Pacific Trade Invest, says: “There’s growing concern that foreign currency debt-to-GDP ratio held by multilaterals – namely EximBank, the ADB and the World Bank – is reaching unprecedented levels in some Pacific Island nations.”

Alison Stuart, division chief for the small states in the Asia-Pacific department of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), adds: “The level of debt is also already relatively high for some countries, notably Papua New Guinea, Samoa, Tonga and Vanuatu – and this is something we are watching. High levels of debt complicate fiscal management and mean that they have to strike a balance between financing infrastructure investment and maintaining debt sustainability.”

Fiji’s ambassador to China, Manasa Tagicakibau, has spoken out against the perception that China is creating a debt trap in the Pacific. He said Fiji takes into account its debt levels before agreeing to any new lending from China, and ensures its debts are manageable.

A complementary relationship

Chinese investment has reached the Pacific Islands alongside that from existing financing partners, not in competition with them. The IMF’s Ms Stuart says the organisation sees positive benefits from the increased support from China in the region.

She explains the investment from China comes as part of a diversification of development partners in the Pacific, which was bolstered in July 2019 by the creation of the Australian Infrastructure Financing Facility for the Pacific (AIFFP). The $2bn AIFFP fund will focus on developing telecommunications, transport, energy and water infrastructure across the Pacific Islands and Timor-Leste. Developing infrastructure is a priority across the Pacific Islands. Ms Stuart says most nations in the region face large infrastructure gaps and financing needs in order to reach the Sustainable Development Goals objectives to alleviate poverty laid out by the UN.

Ms Stuart believes working with any large-scale lender, whether China or any other country, involves risk. “These include potential resource misallocation; for example a lack of quality and viability, with limited positive spillovers to the recipient countries, as well as credit risks for China,” she says. “Therefore, a prudent assessment needs to be made of a recipient country’s credit risks. Where debt sustainability risks are already high, support should be on highly concessional terms or in the form of foreign direct investment and should be transparent.”

Echoing the view of Ms Taylor, Ms Stuart says the nations receiving the loans need to be the ones in the driver’s seat when making decisions about their domestic and external borrowing.

“It is not always easy, but countries need to take an active role in making sure that all projects fit with their development plans, that the pay-off of the projects is adequate and that any attendant risks are properly managed,” she adds. “The IMF sees positive potential benefits from China’s engagement with the Pacific Islands on development, and greater engagement by all development partners is welcome.”

Climate change concerns

The level of support needed is predicated on how damaging natural disasters can be for the Pacific Islands, an issue that is only increasing due to climate change. The region is reliant on a wide range of lenders who can readily provide funds in times of crisis. The islands themselves are responsible for a minimal level of carbon emissions, with Fiji contributing just 0.04% of the global total. However, they are disproportionately hit by the changes in weather, from rising sea levels to an increase in the frequency and ferocity of cyclones.

The Cook Islands’ Mr Brown says tackling climate change is not just about responding after an event. “Pacific Islands nations need to build up climate change resilience. The way that the multilaterals lend could help with this. Borrowing terms could be improved if they were lodged up to 50 or 60 years with 0% interest during the loan term,” he says. “There needs to be investments over the long term, as we expect the impact of climate change on Pacific Island nations and their economies to get worse before they get better.”

Some new partners have been coming forward to provide climate change assistance. In May 2019, the Irish government announced the Ireland Trust Fund for Building Climate Change and Disaster Resilience in Small Island Developing States (SIDS) in conjunction with the ADB. SIDS is committed to operating for six years between 2019 and 2024 with funding of €12m. There will be €1.5m of funding for the last six months of 2019, with some projects already in the pipeline.

Ups and downs

While the Pacific Islands welcome the arrival of new international partners, it does not always mean an additional source of funding. In some cases the new funds are replacing what has been lost from elsewhere, especially for the bigger economies in the region.

Haoliang Xu, assistant administrator and director for the regional bureau for Asia and the Pacific at the UN Development Programme, says the need for support is not always being met. “The nations across the Pacific Islands are very diverse in their population size and the strength of their economies. Even the larger nations can find it difficult to access public financing for the development of their infrastructure,” he adds.

With the increased presence of China acting as a catalyst, the international community is waking up to where it has let its support for the Pacific decline. Australia has recently announced plans to redouble its aid budget for the Pacific region in 2019 and 2020 to $1.4bn, after it slipped to just over $1bn between 2017 and 2018. Aid from the US and the EU has also declined considerably in recent years. And despite the decline, research from Australian think tank Lowy Institute found that Australia still contributed the most in aid of any country, at about 3% of its GDP, ahead of both China and New Zealand in second and third place, respectively. So it is not only China that exerts financial influence.

Among the multilateral institutions, the ADB has pledged to increase its support to Fiji with $600m in loans in the five years between 2019 and 2023 to help private sector development. The ADB will also provide technical assistance grants. While this is a boost for Fiji, it comes at a time when it has lost support from other institutions.

Fiji is no longer eligible for International Development Association funds from the World Bank, as the country has been moved into the middle-income category. The funds are distributed among the poorest countries in the world to reduce poverty, and to countries at risk of debt distress. They are also provided with preferential terms. The loans have no or very low interest applied, and repayments are spread out over 30 to 38 years. There is also a five- to 10-year grace period on repayments. Losing access to this cheap money has been a blow to Fiji.

Mr Brown cautions that losing out on funding is a major problem as some countries grow their economies. “There are difficulties in obtaining growth funds. A line of credit from the ADB which can be drawn down sits on the balance sheet as a $10m liability. This changes the debt profile of a country,” he says.

With their vulnerability to natural disasters, and the disastrous impact this could have on their economies, the Pacific Islands are aware of how much they rely on the multilaterals and the international community to assist them in times of need. These countries are trying to build up their climate change resilience, but assistance for preventative measures is not forthcoming. For the Pacific Islands, the choice of which organisations to work with is not impacted by politics, but finding the most supportive partner.