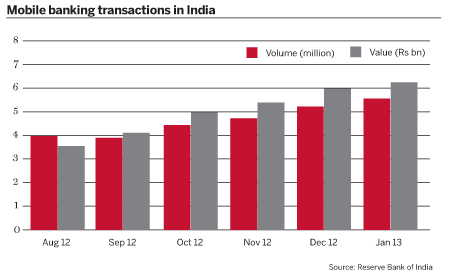

India is finally witnessing an upswing in mobile banking. According to data from the country’s central bank, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), the volume of mobile banking transactions nearly doubled in the past year, from 2.67 million in December 2011 to 5.22 million in December 2012. The value of transactions in this period grew nearly three-fold from Rs1.98bn ($36.8m) to Rs5.98bn.

Editor's choice

More on India

- India: still solid as a BRIC?

- The state of play: India's banks in 2012

- Mobile banking offers glimpse of India's future

- Federal Bank of India targets unbanked with safe, fast and easy payments

More on mobile banking

- Banks to watch in 2013, Tameer Bank

- Tech-savvy Kenyan banks set the template for financial inclusion

- Are banks failing to fulfil their mobile potential?

- Why mobile is banking's most important challenge

- Are non-bank specialists challengers or partners to banks?

- Wallet wars: mobile payment systems fight for critical mass

Out of India's 75 banks, 53 already offer mobile banking services. At the end of December 2012, there were 20 million registered mobile banking customers in the country, and this number is expected to grow several-fold. India has the world’s second largest number of mobile connections, after China and ahead of the US. There are about 900 million mobile subscriptions in India, more than one-third of which are in rural regions. Contrast this to the 400 million-plus bank accounts and 30 million landline connections, and the impact of the mobile becomes apparent in a country where physical infrastructure represents one of the biggest challenges to growth and development.

A 2011 report by consultancy BCG forecasted that by 2015, $350bn of payments and banking transactions could flow through mobile phones in India, compared with the $235bn of credit and debit card transactions in 2011. The report also projected that the fee income from mobile payment and banking transactions shared among banks, telecom operators, device makers and service providers could exceed $4.5bn by 2015.

“Mobile banking volumes have picked up in the past two years,” says Rajeeb Chatterjee, senior vice-president of ATM and mobile banking at HDFC Bank, India’s second largest private sector bank. HDFC Bank is among five banks that cumulatively account for more than 80% of the country’s mobile banking volumes. The others are State Bank of India, ICICI Bank, Axis Bank and Citibank.

Key developments

HDFC Bank first launched mobile banking back in 2000, but the concept was way ahead of its time. There were bandwidth issues and the service itself was unsophisticated. Later, in 2008, HDFC tied up with a couple of mobile payment platforms through which customers could access mobile banking services, but again adoption levels were not very encouraging. It was only in 2011, after the bank launched downloadable apps and a mobile banking site, that the service was able to achieve traction. Mr Chatterjee credits the rise in mobile banking adoption in recent years to the availability of 3G mobile network services and reasonably priced smartphones.

According to Sridhar Iyer, director of digital business at Citibank India, which has also experienced rapid mobile banking adoption in the past two years, the regulatory environment has helped mobile banking to take off in India. RBI issued the first set of mobile banking guidelines in 2008, at a time when mobile banking was still at a nascent stage in the country. These guidelines have since evolved and encapsulate the entire gamut of financial services such as checking account balances, transferring funds across the entire banking network, extending loans and offering an insurance product. The guidelines, for instance, specify a limit of Rs25,000 for cash transfers between a bank account holder and a non-account-holding beneficiary. To encourage small-value transactions, RBI has exempted transfers up to Rs5000 from end-to-end encryption requirements.

Another important development was the launch, in 2010, of the Immediate Payment Service (IMPS), a 24/7 real-time electronic fund transfer on a person-to-person (P2P) or person-to-business basis. Furthermore, although non-bank entities in India are not permitted to accept deposits repayable on demand, they have been allowed to issue mobile wallets up to a limit of Rs50,000, which enables users to make payments and fund transfers.

“We have to give the regulators due credit. They have introduced policies across a range of mobile banking developments including P2P, mobile wallet, USSD [unstructured supplementary service data] and others. This has created an enabling environment for mobile banking. Some transactions such as P2P transfer through IMPS lend themselves to mobile banking,” says Mr Iyer.

He is confident that mobile banking penetration levels will grow significantly. “It took eight to 10 years for online banking to take off. Today several banks have 30% to 40% of their customers using internet banking. NEFT, the National Electronic Funds Transfer system that enables people to transfer money electronically across different banks, took many years to scale up. The proliferation of mobile banking might appear slow at present, but it is bound to pick up,” he says.

Death of online banking?

Given the similarities between mobile and internet banking, it is not surprising that early adopters of mobile banking at most banks are their existing online banking customers. At Citibank, nearly 15% of online banking customers have adopted mobile banking. At HDFC Bank too, 15% to 17% percent of online banking customers use mobile banking. The ratio of mobile banking to internet banking users at HDFC Bank has grown from 1:20 in 2008 to 1:6 in 2013, says Mr Chatterjee. In the next two years, he predicts that the number of mobile banking customers will equal online banking customers and will thereafter surpass the latter.

Mr Chatterjee says that the bank's initial concerns about mobile banking cannibalising internet banking have proven unfounded. “We realised that customers use mobile banking mostly when they are on the move and internet banking is not available,” he says.

Manisha Lath Gupta, chief marketing officer at India’s third largest private bank, Axis Bank, which launched an enhanced version of its mobile banking application in April 2012, is also confident that the two can co-exist. “While demographically and attitudinally there is no difference between online and mobile banking users, the former is limited by access to internet broadband, while the latter is limited by their access to the smartphone," she says. "As the market evolves, the same customer will be using both the services at different times of the day, on different devices.”

Experts suggest that the penetration of mobile banking in smaller towns and cities will be much higher than that of online banking. This is because of the physical infrastructural limitations in India. With only about 30 million landline connections, high-speed broadband access is more readily available on mobile phones than on computers. As a consequence, in smaller towns and cities, exposure to the internet is happening through the mobile, which in turn is expected to drive mobile banking adoption.

Financial inclusion

While banks are predominantly offering a mobile channel to enhance banking services to their existing customers, for the regulators the key focus area is financial inclusion – using the mobile channel to reach a customer base hitherto not served by the formal banking network. “Mobile banking, as we see it in India, is the innovative use of mobiles for 24/7 banking services, which not only provide customer convenience, but also present an opportunity for wider affordable financial inclusion for a large segment of the unbanked and underbanked population,” says Harun R Khan, the deputy governor at the RBI.

It is estimated that more than half of India’s 1.2 billion population does not have access to banking services. This includes both the urban and rural populace, although with a mere 5% of the country’s 600,000 villages having a bank branch, the problem is more acute in rural India.

Recognising that the high cost of establishing a physical bank branch in remote locations remains one of the biggest deterrents to financial inclusion, the regulators developed an innovative concept of using business correspondents, where banks are permitted to use the services of a variety of intermediaries such as insurance agents, post offices and non-governmental organisations as banking representatives. Business correspondents not only help educate people in these areas about the benefits of banking but also act as conduits for cash withdrawals and deposits along with other services.

Mobile-based financial inclusion usually involves payment solution providers or mobile network operators (MNOs) acting as business correspondents. Also, with some of the major telecommunications companies authorised to provide mobile wallets, these MNOs are partnering with banks to offer payment products that link a mobile wallet with a bank account.

In December 2012, State Bank of India (SBI), the country’s largest lender, in partnership with payment services provider Oxigen, launched a mobile wallet targeted at migrant labourers in Delhi and Mumbai that send money to their native villages. It is a pre-paid account accessible over mobile phones, enabling consumers to send remittances to any bank account and transfer funds to other wallets issued by SBI. Users can top up their wallets by depositing cash at any Oxigen retail outlet.

Earlier, in May, Axis Bank tied-up with India’s largest mobile network operator, Bharti Airtel, to offer customers a 'no-frills' bank account with remittance capabilities, empowering customers to use designated Airtel outlets to send money, withdraw cash and even enjoy interest on savings through their mobile device.

“With the mobile having made significant inroads into rural markets, there is immense potential for it to be used for financial inclusion," says Axis Bank’s Ms Gupta. "As long as a physical network of business correspondents or ATMs grows hand in hand, the mobile channel can be very useful for accessing banking services at remote centres.”

Banks take the lead

Mobile-based financial inclusion initiatives of banks in India can be likened to mobile payment systems around the world, such as M-Pesa, which started in Kenya in 2007 and is now available in seven countries. The fundamental difference, however, is that in India, banks are at the heart of the system, while the other initiatives have been driven by mobile network operators. M-Pesa, which is used regularly by more than 15 million customers, generating in excess of 165 million transactions every month, is run by telecommunications company Vodafone.

RBI’s Mr Khan explains that the regulator has consciously adopted a bank-led mobile banking model keeping in view know your customer (KYC), anti-money laundering and customer service aspects. Also, he says, the main focus in the non-bank-led model provided by MNOs is the remittance product, while the bank-led model offers a variety of banking services.

“We have always believed in financial inclusion, mainly through the banks," says Mr Khan. "Our testing ground is the ability of the banks to reduce the financially excluded population and for this, among other methods, tap the ubiquity of the mobile for banking. There has, therefore, been considerable regulatory easing in recent times to enable mobile banking to meet the diverse needs of most users.”

Vodafone has also jumped into the fray in India. In late 2011, it partnered with HDFC Bank as a business correspondent for a pilot mobile banking initiative in the state of Rajasthan. More recently, in December, it extended its M-Pesa service to India when it launched a semi-closed mobile money transfer and payment service comprising a mobile wallet and a linked in bank account with ICICI Bank. Using the wallet, users can immediately start doing domestic fund transfers to bank accounts and M-Pesa wallet holders; and once the KYC formalities are completed and the bank account is active, they can make cash withdrawals from designated outlets as well, says Suresh Sethi, head of M-Pesa at Vodafone India. Vodafone, he says, has a vast network of authorised agents who will enable customers to deposit and withdraw cash from their account and will thus address the challenge of servicing the financially excluded population in remote locations.

Mr Sethi says that Vodafone established a lot from its pilot with HDFC Bank. “The product has to be very simple. Lots of customers are numerate but illiterate,” he says. “The service needs to be multilingual but most phones do not support that so we have to provide customer support in native languages. We also need to educate the agents in the distribution network.” One of the biggest challenges in India, he points out, is the predominance of cash in the economy, “More than 97% of retail payments are in cash. Conversion of cash into digital money is the way forward. What we need is a larger eco-system where digital money is accepted.”

HDFC Bank’s Mr Chatterjee raises similar points. “With regards to using mobile banking for financial inclusion, we have realised that if you have to penetrate rural areas, it is less of a technology issue and more of a distribution game,” he says. “The government is pushing micro ATM-based withdrawals. A good percentage of financial inclusion will be done using it. The government support is there for this programme. Government grants are available for setting up micro ATMs. Nothing like this is there for mobile banking.”

Turning the tide

The regulator is well aware of the challenges facing banks in their efforts to enable financial inclusion through mobile. “The technology, infrastructure, demand, capability – everything is there. Even the regulatory framework is in place. In my view, there are two key challenges: awareness and acceptability. It also needs to be examined if the margins of stakeholders are thin and make the business unsustainable,” says Mr Khan.

Low margins are indeed a key challenge. Given the low transaction values and low volumes, the business case is often not attractive for the financial institutions and MNOs, and several financial inclusion projects have not extended beyond the pilot stage.

Mr Khan believes that one government initiative that could turn the tide generating the right volumes to make the financial inclusion initiatives attractive for the various stakeholders is the electronic benefit transfer for government welfare schemes. Under this initiative, all cash transfers and subsidies to the lower income populace will be transferred directly into the accounts of the beneficiaries. This scheme was rolled out January 2013 in several states in the country.

Mr Sethi also believes that the electronic benefit scheme will create a positive impact. “In Kenya, P2P transfer is what pushed the case for mobile payments. In India, direct cash transfers will play that role,” he says. “This could be the game-changer and allow us to hit the inflection point in India just like in Kenya.”