In the game of chicken, two cars race towards each other head-on and the first driver to take evasive action is the loser. Japanese investment bank Nomura may not be speeding towards another car, but it is definitely well down the road with a global expansion strategy in which it cannot afford to lose its nerve. If it blinks, everything it has worked towards in the past three years could be lost.

Editor's choice

When it snapped up Lehman Brothers' Europe, Middle East and Africa business for a couple of dollars and its Asian business for $225m three years ago, Nomura thought it had grabbed the bargain of the century. But while the acquisition itself was remarkably cheap, turning it into a profitable purchase has been more challenging than senior managers could ever have anticipated.

Expensive staff had to be hired and retained, and the crucial missing US piece of the puzzle had to be built. But in late 2008, none of the management team saw this as a problem. Nomura would build out the business in the downturn and emerge ready for action in the upturn.

Little did Nomura, or anyone else, think that the financial crisis would morph into a sovereign debt crisis and that three years later, the global economy would still be facing one of its most difficult periods for a century, with calamitous repercussions for capital market activities and investment banking revenues.

Neither did Nomura anticipate that the window of opportunity for grabbing market share from weakened competitors would be so short. State bailouts and rescue mergers meant that the banks worst hit by the subprime crisis re-entered the market much faster than anyone believed possible in the third quarter of 2008. What many saw as a logical but audacious move has faced extraordinary headwinds before it can pay off.

International gamble

Nomura's most recent financial results spell out the scale of its challenge. For the first quarter of its fiscal year 2012, ending in June, the group generated a pre-tax profit of ¥34.4bn ($448m), versus ¥6.5bn in the same quarter a year earlier. However, the increase was boosted by a group reorganisation; returns remained very low and revenues fell in most of its business lines.

The wholesale division – Nomura's investment bank – made a loss of ¥14.9bn. Within wholesale, global markets made a pre-tax profit of ¥6.7bn, down just 3% quarter on quarter, but investment banking made a loss of ¥20.8bn. Most analysts suspect that its second-quarter results for fiscal year 2012, due on November 1, 2011, will offer more of the same.

Everything hinges on the success of the bank's international operations, which are struggling to keep their head above water even as they are subsidised by Nomura's powerful domestic business.

“Nomura's Asian operations will take two to three years to be sustainable. In the US, its fixed-income operations are profitable, but the start-up cost for the equity business has been an offsetting factor. In Europe, the sovereign crisis helped to turn a profitable business into an unprofitable one. When you add it all up, the international operations are still in the red, and turning that around is going to be a challenge,” says Hideyasu Ban, managing director and financial sector analyst at Morgan Stanley in Tokyo.

A need to grow

Nomura's global push was a matter of necessity as much as ambition. The undisputed champion of Japanese capital markets and retail brokerage, nonetheless it faced a shrinking and increasingly competitive domestic market. To sustain itself, let alone to grow, Nomura had to go overseas, says Takumi Shibata, Nomura's chief operating officer (COO) and one of the key architects of the Lehman acquisition.

“Japanese equity transaction volumes represent only about 5% of the global total, so even if you are the king of Japanese equity, you are not really the king of anything. If you look at the [Japanese] government bond market, 97% of the bonds are owned by Japanese investors, so where is the room for international businesses?” asks Mr Shibata.

Moreover, Nomura's corporate, institutional and retail clients are increasingly global, so it was a necessary progression, he says. “A good deal of Japanese companies have more than 50% of their sales outside of Japan; the same kind of trends can be seen with Japanese institutional investors. [Our] mindset has to be global to meet our clients' needs. Part of the reason that we felt we needed to do something comes from the profile of our clients in the domestic market,” says Mr Shibata.

Japanese equity transaction volumes represent only about 5% of the global total, so even if you are the king of Japanese equity, you are not really the king of anything

History abroad

This is not the first time that Nomura has made a bid to turn itself into more than the biggest securities house in Japan. The most international of Japan's financial services firms, it has a history of forays abroad – beginning as early as the 1920s – but it was not until the 1980s that it made real headway. It became the first Japanese member of the London Stock Exchange and the first Japanese primary dealer in US treasuries; by the middle of the decade, it was the world's largest securities firm, with net capital in excess of $10bn – then exceeding the size of US powerhouses Merrill Lynch, Salomon Brothers and Shearson Lehman combined.

In the late 1990s it was a pioneer of principal finance and proprietary trading. At the turn of the century, it was busy buying up UK plc via its principal investment unit. At one time, it was the UK's largest public house owner, with 7000 pubs on its books; it owned a third of all UK passenger trains and managed 2000 shops that belonged to Thorn, the UK television rental shop company.

But these earlier expansions had mixed results. In 1998, losses in principal finance led Nomura's European business to post losses of $564m, while the US operations lost nearly $1.2bn in the same year, leading the group to report a $1.76bn loss for the fiscal first half. Following the collapse of the US commercial real estate loans business and in the wake of Russia's debt default that year, Nomura Japan was forced to inject $1.2bn on top of a hefty equity infusion to rescue the haemorrhaging US operations.

To put the total $1.78bn rescue package in context, it was about half the size of the rescue a month earlier of hedge fund Long Term Capital Management by a consortium of 14 banks and brokerages.

No turning back

Shareholders hope that this time around Nomura will be able to turn its bold move into a sustainable business without such yo-yo returns. They are having to be patient. Nomura's share price has plummeted by 70% since the Lehman acquisition. Clearly, Nomura is not alone – Japanese banks and the financial sector as a whole have faced similar value destruction – but some analysts question how much longer investors will wait for the strategy to pay off.

“Shareholders are frustrated with the lack of progress; the recent shift in strategy and the announced cost cuts are clearly an attempt to address those concerns,” says Jun Oishi, an analyst at investment bank Keefe Bruyette & Woods in Tokyo. “Nomura has enough capital to stick it out for at least a couple more years, but it is unclear how much longer shareholders that have stuck around will wait for returns to pick up.”

However, most agree that Nomura has gone past the point of no return. Having invested heavily in creating the international platform, to turn back now would be to throw good money down the drain. Some have suggested that for CEO Kenichi Watanabe and COO Mr Shibata, this is make or break for their careers at Nomura.

There are signs that Nomura's nerves may be starting to fray. In a sure sign of management anxiety, the interviews for this feature in Tokyo and in London were at the last minute cancelled and then reinstated; then two key interviewees in London could no longer be directly quoted. Moreover, many suspect that the 'recalibration' of the business announced in July means that Nomura is effectively backing away from its ambition to take on the global bulge bracket investment banks, the bold statement it made after the Lehman acquisition.

Mr Shibata stresses that Nomura's international plan remains the same. “We have no intention of backing away,” he says. “Our commitment to the global business is real because that is where we believe the opportunities are.”

We have no intention of backing away... Our commitment to the global business is real because that is where we believe the opportunities are

Taking market share

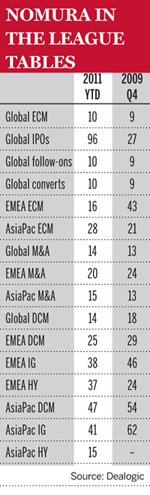

The irony is that Nomura is taking market share, albeit of a shrinking fee pool. The problem is that it has so far failed to be enough to offset the cost of the build. Morgan Stanley's Mr Ban has been tracking global investment banking revenues since the first quarter of 2009 and his data show steady improvement across two out of three sectors.

By the second quarter of this year, Nomura had increased its share of global equity revenues from 0% (Nomura's equity business made a loss that quarter) in the first quarter of 2009 to 4.7%, and in fixed income its share of the revenue pool had risen from 2.1% to 6% in the same period. Investment banking has been far more volatile, however, seeing its share of the revenue pool rise from 1.5% to peak at 3.7% in the fourth quarter of 2009, before falling to 3% at the end of the 2010 and falling again to 1.3% in the second quarter of this year.

A senior investment banker agrees that the bank has not achieved as much as it hoped in the timeframe, but says the trend in the investment banking business is going the right way.

“It takes time to build relationships and become a relevant force in investment banking. Looking at our business, we are continuing to make progress... We have been up quarter on quarter in most of our businesses most of the time, and year on year... But it's relative rather than absolute [performance], so when you look at the absolute earnings numbers, they are not where we would like them to be... but the direction of travel is clear.”

Lack of confidence?

The collapse of market confidence and deal activity have not been kind to any investment banks, but the investment banker argues that it has had a greater effect on Nomura as it tries to establish a track record.

“We have got more than 20 initial public offerings [IPOs] in the pipeline here in Europe; but execution has been very slow because of the market. Nomura only entered the business at the end of 2008, and better market conditions would have allowed us to build our track record more quickly,” he says. “For our major competitors, that is less of an issue because they have already done a multitude of IPOs over the 2005 to 2010 period and have that track record.”

More importantly, he argues that both Nomura's pipeline and recently announced deals (yet to be reflected in Nomura's disappointing showing in league tables) demonstrate the growing strength of the bank's cross-border merger and acquisition (M&A) franchise, particularly in the Asia-Pacific region. “We have made obvious progress in Asia-Pacific over the past six months in investment banking,” says the investment banker. “We have announced 10 M&A transactions in Asia over the past four months... so I think there is definitely a clear track record of progress.”

Asian salvation

Crucially, deal flow is emanating from across Asia and not just Japan (where the bank is working on about 80 potential M&A 'situations', it says). Senior management make much of Nomura being an 'Asian' bank, but if Japan is stripped out, it has historically failed to capture a significant amount of investment banking deal flow. This is partly because Asia continues to be predominantly a bank market, where investment banks have tended to lose out to lenders.

Nomura hopes that is changing; in the past couple of months, seven cross-border transactions have been announced spanning Japan, China, Australia and Europe. For example, Nomura acted as sole financial advisor to Bright Food, one of China's largest food and beverage companies, in its acquisition of a 75% stake in Australia's Manassen Foods. This was Bright Food's first major international transaction and the largest investment by a Chinese company into the Australian consumer sector.

In another deal announced in August 2011, Nomura is financial advisor to India's GMR Energy in its acquisition of a 30% stake in Indonesia’s PT Golden Energy Mines, India's largest outbound metals and mining transaction in 2011.

Growing prospects?

A senior executive in global markets is also upbeat about his division's prospects for growth. Part of his confidence stems from the firm's strong presence in the cash markets. Nomura has leading positions on the Tokyo Stock Exchange and the London Stock Exchange, and has a growing share of volume on the New York Stock Exchange via its electronic trading and agency brokerage business, Instinet, on which in the last quarter, average daily trading volumes had increased by 42% over the same quarter a year earlier.

The bank has placed a great deal of emphasis on ensuring the research offering supports the markets business, and that is making headway. In the Institutional Investor 2011 All America Fixed Income Survey, for example, Nomura ranked seventh overall for the second year and rose significantly across a range of categories, including broad economics and strategy, where it rose from 12th to fifth place; foreign exchange (FX) where it ranked first: and agency residential mortgage-backed security, where it ranked second.

Nomura also did well in Greenwich Associates' latest survey of US fixed-income investors in June, where its overall market share rose from 0.5% to almost 2%, with growth in US Treasuries, mortgage-backed securities, consumer asset-backed securities and high-grade credit. The bank's penetration in fixed-income e-trading jumped from 2% to 9%, and it ranked first in terms of the proportion of clients expecting to increase business with the firm in the next 12 months.

Solid foundations

The building blocks are there, says the markets executive. “There is more search for alpha both in equities and fixed income so our ability to add value through intellectual capital is far greater and it is up to us,” he says. “If we have good sector analysts in equities, we'll get the business. If we can offer solutions, through good research in fixed income or good traders, we will get the business. We have a strong structured solutions business that is also linked with global finance and banking and we do very well with that.”

The market executive says that Nomura's plan is to make an advantage of the firm's relatively small size and its new-build status. He says this makes Nomura more nimble and less silo-based than its rivals, and this means it can be “disruptive in the market”. For example, the bank has combined its FX and rates businesses to capitalise on the linkages between them, and this would be much more difficult at a large commercial bank, he says. “I have been able to combine the [FX and rates] teams because I do not have an entrenched vested interest in either asset class. I can do what I think the markets and the clients require.”

He also believes that the emerging regulatory environment – with the emergence of new market structures and tougher capital requirements – could be to Nomura's advantage. While some banks will have to scale back to meet capital requirements or fit old business models to new infrastructure, Nomura is well capitalised and does not have a legacy business to reshape. “We have got the ability to grow at our own pace [but] it is far tougher [for competitors] to get smaller. We are happy to fall in line with the new regulatory environment because we do not have the incumbency. [Because] we do not have a swaps book of 10 years to protect, we are happy to have clearing houses, for example,” he says.

Target sectors

Nomura's recent Asian successes, its growing track record in the power and energy sector, and other recent deals such as its advisory role on Bain Capital's acquisition of Australian software company MYOB and Blackstone Group's acquisition of outdoor clothing company Jack Wolfskin, demonstrate that it is beginning to gain traction in its key industry and product areas: natural resources, financial institutions, consumer and financial sponsor-related business. “These [sectors] are top of the list because [they account for] the largest share of the fee pool,” says Jasjit Bhattal, president and CEO of Nomura's wholesale division.

Focusing on where the revenue is and investing only in areas where the investment bank can quickly turn competitive advantage into profit has become the new mantra for Nomura's senior management. They talk of recalibrating the wholesale division's strategy; of target markets and productive niches.

Anticipating a period of deleveraging in the European financial sector, for example, Mr Bhattal places increased emphasis on what he calls 'non-traditional' business: complex asset financing and hedging transactions, and asset and liability management. “We are more focused on the more innovative aspects of the business... structured financing solutions, hedging, [and] the monetisation of non-core assets is going to be far more central.”

A very targeted approach is reflected in Nomura's build-out in the US, which is already profitable. The talk of an acquisition to get the business to scale more quickly, or any notion of an expensive investment banking buildout, have been forgotten in the more straightened environment of 2011. Now, it is all about finding profitable segments that Nomura can monetise quickly and build on later as markets return to normal.

In the US, this has meant a focus on the markets business and selective growth in advisory around Nomura's target industries.

“We started with certain capital markets parts of the business and in the investment banking sphere we have been very focused as to which industry groups [we build],” says Mr Bhattal. “In global markets, within fixed income, we have focused on rates, credit and non-G10 FX. In all three, we are well ahead of our initial projections. Clearly, the fixed-income environment has been reasonably good, but nonetheless as a new entrant, we have punched well above our weight. In terms of equities, the approach has been similar... we have a very strong expertise in specific areas and we focused on these, so when it comes to electronic trading, statistical arbitrage or program trading, we have done exceptionally well.”

The bottom line is profit

For all of Nomura's progress and the management team's solidarity about the strength of its commitment to an international strategy, it has to start paying off more substantially and more sustainably soon. Some argue that the cost-cutting plan already announced (which will be achieved by getting rid of the non-performers, says Nomura) will have little impact on revenue or profitability, and that only by reaching at least break-even point will shareholders be kept onside.

“Investment banking, particularly in Europe, should be downsized,” says Makoto Kasai, director of fundamental analysis at Citi in Tokyo. “Investment banking has been losing about ¥15bn every quarter since the Lehman acquisition, so it needs to reduce its costs by about the same amount. Cutting $400m is way off the mark. If Nomura could reach break even, then most investors would support continued expansion. But they have been waiting for 12 quarters [since the acquisition] and I do not see how Nomura will be able to increase market share by enough to make up for the cost of expansion.”

If Nomura could reach break even, then most investors would support continued expansion. But they have been waiting for 12 quarters [since the acquisition] and I do not see how Nomura will be able to increase market share by enough to make up for the cost of expansion

The senior investment banker acknowledges that the cost base looks high, but counters that Nomura is winning more and more deal flow, and that the success of the broader business depends on having the full investment banking capacity that has been built. For example, he argues that without full capacity in Europe, Australia, China, Hong Kong and Singapore focused on the natural resources business, Nomura cannot deliver to clients the industry insight, or the ability to raise capital and trade the assets that they expect.

“There are no half measures in this business,” he says. “We have to be there and be competitive and be able to deliver what the clients want.”

He argues that Nomura's client proposition is beginning to deliver – if a lot later than the bank had hoped. He also thinks that the operating environment that is emerging will help to level the playing field, and remove some of the competitive disadvantages that have stymied Nomura's progress. The uplift provided by government support is already being removed in bank ratings; capital is becoming ever more scarce; funding is tight.

“Our opportunity is starting to look today more like we thought it was going to look in 2008,” he says. “All of a sudden, all the balls are up in the air again with how the industry evolves.”

The great deleveraging

Mr Shibata agrees that the new landscape will play well to Nomura's strengths. He thinks it may finally usher in the kind of industry shake-up that Nomura anticipated in 2008. “My hypothesis is that the European banking scene is undergoing structural change, which could change the banking landscape for ever,” he says.

European banks could face a tough few years in terms of funding, capital raising and balance sheet cleaning, he says, while Nomura is willing to become one of the solution providers because it is ready.

“Our Tier 1 capital ratio is in excess of 16% under Basel II and we are targeting to maintain about 10% for Basel III. Other banks will have to shrink their balance sheets just to reach 7% or 8%; we are already where other banks need to be by the time Basel III comes into place,” says Mr Shibata. “Also, we have a very clean balance sheet simply because [unlike commercial banks], we are forced to mark-to-market almost everything. We have long-term funding capability – with 80% of our unsecured borrowing having a maturity of one year or more.”

In what Mr Shibata thinks will be a five-year period of deleveraging by commercial banks, particularly in Europe, good assets will be sold in the US, Asia and in Europe, and Nomura is ready.

“These assets need to find new homes; the big private equity players might talk to commercial banks direct, but others will need some sort of intermediation,” he says. “If you add insurance companies to the list of firms needing solutions, we are there. We do not publicise what we do, but we have been involved in a number of deals that [help] insurance companies to strengthen their capital base and de-risk their portfolios. These kinds of transactions could only have been done by a company with a clean balance sheet.”

The long game

After a history of several false starts, Nomura has put everything on the line to complete its transformation into a global investment banking player. So far, its efforts have not been rewarded to the degree that the cost of expansion demands. Clearly, many of the reasons for that lie outside of its control, but bottom line profits have to be delivered or its global push will once again run out of steam or be halted by frustrated shareholders.

However, it is clear that Nomura's senior management believe that the gamble is not yet played out. They argue that Nomura has the right business in place, albeit that the critical US element is still being built, and the right capital and funding base to capture more deal flow as the global financial industry evolves under a tough and more restrictive regulatory regime. They key is for the bank to hold its nerve and stick to the plan.

“The history of our industry shows that in difficult periods you adapt. You keep your core people, manage your costs, you stay focused on your clients and you get through it, because the markets will get better,” says the senior investment banker. “And those businesses which have stood by their clients, been focused on what they are doing, and have adapted will end up being more successful.”