The South Korean banking sector is the latest to be taken by storm by new entrants in the form of IT and retail firms. After giants including e-commerce company Alibaba and investment holding company Tencent disrupted the Chinese banking sector, the Korean Financial Supervisory Commission (FSC) has announced that it will introduce the country's first internet-only bank by the end of 2015.

The announcement has split the South Korea banking sector in two – into the lenders that are joining the consortia competing for the licence, and the lenders that are ignoring them completely. To the second group, building digital banking organically is the only strategy that makes sense.

The new internet-only bank will be bringing additional competition in an already ferociously competitive sector, especially after Hana Bank’s landmark acquisition of state-owned Korea Exchange Bank (KEB) left key players in the market worried.

South Korean banks also do not have it easy on a macroeconomic level, with the country’s economic growth faltering and low interest rates squeezing net interest margins (NIM). In this tricky environment, expanding abroad and diversifying product offerings have become fundamental. But unless regulatory hurdles – mostly affecting financial holding companies – are addressed, South Korea’s top banks may struggle to function to full potential.

A digital intervention

The FSC announced that it will introduce the inaugural internet-only bank before the end of 2015 to increase competition and innovation in the South Korean banking sector. Backed by IT firms, three contenders – Kakao Bank, K-Bank and I-Bank – have applied for the licence.

Led by South Korea’s leading mobile chat app Kakao Corporation, Kakao Bank is teaming up with 11 partners, including Kookmin Bank – the second largest South Korean bank by Tier 1 capital according to The Banker Database – Netmarble Inc, an online game software provider, and eBay Korea.

KT Corp, South Korea’s largest fixed-wire operator, is backing K-Bank. Woori Bank, the fifth largest lender in the country by Tier 1 capital, has joined this consortium together with IT solution provider Nautilus Hyosung, among others.

New entity I-Bank is being backed by Interpark Corp, a South Korean online shopping mall operator, and Industrial Bank of Korea (IBK), the seventh largest South Korean bank by Tier 1 capital, is the local bank joining this group. Woori Bank, Kookmin Bank and IBK were not available for comment.

Going it alone

The third and fourth largest banks in South Korea by Tier 1 capital – Shinhan Bank and KEB Hana Bank – have decided to not get involved in these consortia. To them, focusing on their own digital banking offering is a better strategy.

According to Yong-byoung Cho, CEO of Shinhan Bank, Shinhan’s own digital banking is a notch above what the consortiums can offer. “Shinhan Bank plans to provide its own accessibility, customer convenience and life contact services [through the app Shinhan S Bank], the quality of which is higher than those served by internet primary banks,” he says.

Shinhan Bank’s strategy to collaborate with IT firms is at odds with joining these consortia, adds Mr Cho. “The advantages of this approach are, unlike composing a consortium, building co-operative relationships with various partners and minimising cannibalisation issues with existing banks.” Shinhan is also creating products aimed at retaining customers who might be tempted to move to the internet-only bank.

Byoungho Kim, vice-chairman of Hana Financial Group, agrees that joining the internet bank would cannibalise KEB Hana Bank’s existing digital banking work. “This would provide low value-added to us," he says. "[Working] as a group could be a challenge. Instead of having a separate internet banking institution with scattered ownership, we want to strengthen our own internet banking business.”

To back Mr Kim’s argument, some US lenders that once had separate internet banking facilities are now re-merging these into the parent bank.

The collaborations KEB Hana does value are with foreign IT companies and retailers with huge customer bases. It recently launched a partnership with Alibaba’s third-party online payment service Alipay to provide tax refund payment in South Korea and a payment settlement channel for Alipay users purchasing goods in the country.

Saturation point

Although Shinhan and KEB Hana are steering clear of the consortia, the new internet bank could still challenge these traditional South Korean lenders. For instance, the new internet bank will target mid- to low-tier customers, who are also targeted by Hana Financial Group’s savings bank and capital subsidiaries.

More importantly, with the FSC’s licence, the new internet bank will be able to fund itself through deposits. “This means it could raise deposit rates [to be more competitive], which would then hit the NIM further. It will be a vicious cycle,” says Mr Kim.

But the competition in South Korea’s banking sector could get even fiercer. Notably, Hana Bank’s acquisition of KEB is also intensifying competition among the country's top banks, according to Mr Cho.

Hana Bank’s long-winded acquisition of KEB began in 2012 and was completed only in 2015. Acquiring a public entity as a privately owned bank meant that trade union resistance was among the hurdles that slowed the deal.

Now completed, the acquisition will add about 350 branches to Hana’s existing 650, bringing it up towards the 1000 mark – the average among South Korea’s leading banks. The deal also adds KEB’s strength in foreign exchange and corporate banking to Hana’s expertise in retail and private banking. “It’s a perfect match,” says Mr Kim.

With mergers and acquisition opportunities quickly disappearing in South Korea’s saturated market, Hana chose a good time to acquire KEB, according to Mr Kim. “Consolidation is already happening, faster than in other emerging countries. There aren’t that many merger opportunities left. Woori Bank is the only one in the market,” he says.

The South Korean government has repeatedly tried to sell its 51% controlling stake in Woori Bank, to recuperate the more than $12bn it invested in bailing out the bank and its affiliates a decade ago, but to no avail. A block trade is now on the table. The government is looking to sell 30% to 40% of its stake in a number of blocks ranging from 4% to 10% each.

Critics have accused this transaction format of losing the government the control premium, but Mr Kim argues it might be the only solution in today’s market. “Critics should focus on the practice, not the theory.”

Sluggish economy

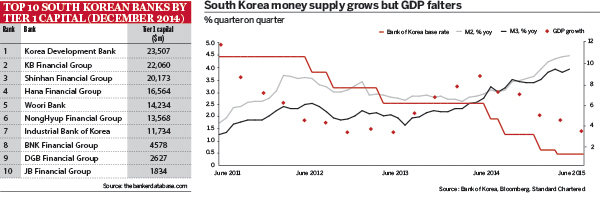

In addition to intensifying competition, banks are also having to deal with South Korea’s slow gross domestic product (GDP) growth, combined with a low-interest-rate environment. Although South Korea’s GDP growth in the third quarter of 2015 exceeded expectations at 1.2%, quarter on quarter, the underlying economic fundamentals are not promising. Low export demand is still impacting industries such as automobiles and shipbuilding. Private consumption remains tepid and unable to boost the local economy, argues HSBC in a report.

“[We] see Korea's growth staying subdued and below-trend over the medium-term,” says the HSBC report. The bank expects the country’s full-year 2015 GDP growth to hit 2.5%, down almost a full percentage point from 2014 (3.3%).

Meanwhile, Bank of Korea – the central bank – is keeping interest rates low at an unprecedented 1.5% in the hope of revitalising the economy. But market liquidity and rapid credit growth have not boosted the real economy yet. Economic growth has yet to benefit significantly from low rates, argues Standard Chartered.

In addition to not reviving growth, low rates are also squeezing local lenders’ NIMs. The industry-wide NIM in South Korea was 2.3% five years ago, but the figure has now dropped to 1.6%. This means that banks struggle to make money through lending.

“In the Korean economy, the three lows [low growth, low profit, low interest rate] have become prolonged… Korean banks are doing their best to secure NIM to improve profitability, and are seeking ways to diversify profits, such as increasing non-interest income and expanding [their] global business,” says Mr Cho.

Quantitative easing might not even be over yet. HSBC predicts two further rate cuts in the first and third quarter of 2016, which would bring South Korea’s rates to 1%. "There is a lot of social pressure to not increase rates,” says Mr Kim.

Regulation holding back

Regulation is also making it hard, particularly for South Korean financial holding companies, to face a downbeat local economy. After customer data was stolen from KB Kookmin Bank, Lotte Card and NH Nonghyup Card by a Korea Credit Bureau computer contractor and sold to marketing firms in 2014, the FSC passed the financial holding act, which bans bank holdings’ subsidiaries from exchanging customer information for marketing purposes. This can be done only for risk and internal management.

Limiting cross-subsidiary information exchange narrows business opportunities. “The financial holding cannot play the role we originally intended,” says Mr Kim. “It is not like Europe’s universal banks. We have industry-by-industry legal systems, which prohibit the financial group from truly working as a single company.”

KEB Hana is working around this regulatory obstacle through a new app, Hana Members. The app aggregates users’ loyalty points from schemes associated with e-commerce platform SK Planet, leading retailer SSG Shinsegae and conglomerate CJ, which operates in the food, home shopping and entertainment industries, among others. Users can also transform aggregated points into cash.

“This is the first app of its kind. And the first tool to make our financial group act as a single company, since it overlaps across different subsidiaries, such as Hana Credit Card,” says Mr Kim.

The financial holding act is one example of a regulatory environment that is not liberalising quickly enough, according to many local bankers. Even having a pro-liberalisation, former banker as FSC chairman in the shape of Yim Jong-yong is not pushing reforms forward. “He has experienced the field with Nonghyup Holdings and has the zeal to rid the market of constraints to help it grow. But it seems like the speed of reform is not what he originally wanted, probably due to political pressure,” says one senior banker in South Korea.

Crossing borders

To escape the low-growth prospects at home, top local banks are expanding abroad to diversify revenue sources. In 2015, Shinhan Bank has grown its presence in Japan, Cambodia, Vietnam and China. In August 2015, the lender became the first South Korean bank to acquire a banking licence in Mexico and it set up a branch in the Philippines capital Manila in November. Dubai could be the next stop, according to Mr Cho.

Shinhan also acquired two banks in what is largely considered to be one of the most protectionist markets in the region: Indonesia. The lender acquired a 40% stake in Jakarta-based Bank Metro Express in April 2015, followed by a 75% acquisition of Surabaya-based Centratama Nasional Bank later in the year.

By law, foreign banks can only buy up to 40% of an Indonesian lender unless they are willing to buy two local banks and then merge them into one. Considering this, Shinhan Bank could be heading for an Indonesian merger itself, according to some analysts.

KEB Hana Bank is also developing overseas. By 2025, it aims to generate more than 40% of its revenues offshore. It is currently building on its existing operations in the Philippines, Vietnam and Myanmar. The next destinations could be Cambodia and India, which have long been a target for the lender, says Mr Kim.

KEB Hana is not internationalising only through banking. In Myanmar, it set up a microfinance institution and it started a leasing business in Indonesia. In China, it set up a financial leasing joint venture in 2015 with China Minsheng International targeting companies in the manufacturing, solar, energy and machinery sectors.

Despite rapid internationalisation, South Korean bankers are eyeing neighbouring countries with caution, especially China and Indonesia. “These markets are extremely correlated with the world economy, especially the US. Their currencies and economic growth are directly affected by external factors,” says Mr Kim. KEB Hana Bank has the largest number of branches among South Korean banks in China – more than 30 – and it has more than 40 in Indonesia.

China blow

Any economic slowdown in China has a huge impact in South Korea. Beijing accounts for one-quarter of the country’s exports as its top trading partner, which means many South Korean companies are seeing their performance deteriorating on the back of decreasing export demand from China.

China’s troubles, including the stock market crash of August 2015, have also hit South Korean individuals. “Korean customers invested in the Chinese stock market directly and indirectly. [Ever] since the large decrease of the Chinese stock market last June, it [has been] distressful,” says Mr Cho. “Shinhan is carefully providing individual asset management for customers who have invested in the Chinese market, making sure they do not feel insecure because of expanding financial market volatility.”

South Korean banks are not operating in an easy environment. The market is still mired by 2014’s banking corruption scandals; the economy is growing slowly; and some of South Korea’s neighbours – especially China – are underperforming. The FSC’s decision to create an online only fully licensed bank will put further pressure on conventional banks. But it also provides some movement in an otherwise stagnant regulatory backdrop. If the sector wants to work to full potential, regulation must be equally reformist for conventional banks and financial holding companies, which represent the biggest chunk of South Korea’s banking sector.