These are challenging times for Croatian policy-makers. Last October, after several months of haggling between Zagreb and the European Commission over Croatia’s willingness to cooperate with the United Nations War Crimes Tribunal in the Hague, the EC decided to open EU accession negotiations with Croatia.

Although briefly boosting the popularity of the centre-right minority cabinet of premier Ivo Sanader, membership negotiations will place heavy demands on the government, particularly in the areas of healthcare reform, environmental protection and competition policy.

While the clear prospect of EU accession, coupled with adherence to a 20-month, $143m stand-by arrangement with the IMF, provide strong ‘external anchors’ for the reform process, the fragility of the coalition government – which faces attacks from the far-right Croatian Party of Rights (HSP) – is hindering much-needed structural changes.

A modernised sector

Yet one sector that is already modernised and able to cope with the competitive pressures of the single market is the banking industry. After years of regional political turbulence and bank failures, according to a report by Standard & Poor’s, the sector is “profoundly rehabilitated [and] restructured following [a] period of economic stability and investment by foreign banks”.

While the level of financial intermediation (total banking sector assets or loans as a percentage of a country’s gross domestic product [GDP]) in south-east Europe is lower than in the more advanced central European countries that joined the EU in May 2004, Croatia has the most developed banking market in the region. According to research from Austria’s Raiffeisen International, retail loans in Croatia account for more than 30% of the country’s GDP, compared with roughly 15% in Hungary, 10% in the Czech Republic and 50% in the eurozone.

Croatia also leads the region in the number of debit cards per thousand inhabitants and in residential mortgage loans as a percentage of GDP. According to Raiffeisen, at the end of 2004, mortgage loans in Croatia accounted for 10.3% of GDP, compared with 9.4% in Hungary, 5% in Poland and 34% in the eurozone.

“The banking industry is the one sector of the economy that is already there, supported by a strong culture of retail lending.” says Milivoj Goldstajn, a board member of Zagrebacka Banka, a subsidiary of Italy’s UniCredit and Croatia’s largest lender. “We don’t need to make the transition [to western-style capitalism].”

“I would rate [the sector] as the most advanced in central and eastern Europe,” adds Wolfgang Peter, chief executive of HVB Splitska Banka (currently part of UniCredit following its acquisition last year of Germany’s HVB but in the process of being sold to resolve antitrust issues).

Foreign growth

Foreign investors have contributed significantly to the modernisation of Croatia’s banking system through a transfer of know-how and financial support. In 1997, international lenders held only 4% of the sector’s assets; they now control more than 90%. The two largest banks – Zagrebacka and Privredna Banka Zagreb (PBZ), owned by Italy’s Banca Intesa – account for 43% of the market. The next four biggest lenders, which have a combined 30% market share (giving Croatia one of Europe’s most concentrated banking markets), are Raiffeisen, Austria’s Erste & Steirmarkische, HVB Splitska Banka and Austria’s Hypo Alpe-Adria Bank.

According to new data from the Croatian central bank (HNB), there are currently 34 banks in the country, four savings institutions and six representative offices of foreign lenders. After a crisis in the late 1990s, a stringent banking act was introduced in July 2002. This harmonised regulations with EU laws; strengthened prudential supervision; raised capital adequacy requirements; and forced lenders to publish their audited financial statements in accordance with International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS), thus reporting on a consolidated group basis.

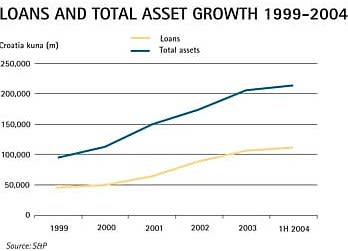

After peaking at 21.3% in 2000, the regulatory capital adequacy ratio was a satisfactory 14.4% last year, but is falling due to banks’ rapid asset growth. Banks’ earnings, fuelled by retail lending, have increased dramatically in the past five years, giving the sector a pre-tax return on assets in 2005 of 1.8% and an after-tax return on equity of 16.5%. According to S&P: “Spreads of about 7%-8% are comparable with those in Slovenia and Poland, considerably lower than in Romania and Bulgaria, and slightly higher than in the Czech Republic and Slovakia.”

Restrictive measures

Unlike most other emerging markets, household loans in Croatia account for the bulk of banks’ lending, comprising 48.3% of total loans, with corporate and government loans accounting for 39% and 10% respectively, according to central bank data.

Aggressive retail lending has been supported and encouraged by local banks, through borrowing from their parent institutions. A credit boom in 2002-03, with loans in 2002 soaring by 30%, triggered a raft of Draconian measures from the central bank to curb retail lending. These were primarily aimed at slowing the rapid growth of private sector external debt which, at nearly 70% of the country’s current account receipts, is by far the highest in the region.

The measures included the introduction of credit growth ceilings for individual banks and strict reserve requirements – particularly regarding the share of blocked reserves and the amount to be held against foreign-currency liabilities – designed to drain excess liquidity from the banking system.

“These are very restrictive measures but we have to slow the growth of [external] indebtedness. Since 2001, banks’ share of total external debt has increased, while the government’s share has fallen. Banks are borrowing from their parent groups abroad, which is an unfortunate consequence of foreign ownership,” says Zeljko Rohatinski, the governor of Croatia’s central bank.

The restrictions have curbed the growth of retail lending significantly. “Total loan growth has halved, but it’s still strong enough to impact negatively on the current account deficit and external indebtedness,” says Mr Rohatinski. He adds that the policies are designed to make foreign borrowing unattractive and they will have to wait and see what impact the latest measures will have, such as the increase in December 2005 of the marginal reserve requirement on foreign funding to 55%.

The severity of the measures has irritated lenders. In one of its recent notes to clients, Raiffeisen says: “Monetary policy has to rely on blunt instruments. It is almost impossible to curb the growth of consumer loans without also negatively affecting credits to enterprises, something central and eastern European countries can [ill] afford.”

Mr Peter adds: “These are the harshest measures in Europe and they are reducing our margins. I understand that the central bank has to control foreign indebtedness. But it’s wrong to pin all the blame on the banks. We’re just intermediaries. The government is causing many of these problems.”

Mr Goldstajn, whose bank has nearly one-fifth share of the retail market, calls the central bank measures “heavy-handed, arbitrary and discretionary”.

“It makes foreign funding practically impossible,” he says. “We have to meet the expectations of our shareholders and it is becoming increasingly difficult to deliver in this environment.” He recalls waking up in London in July 2004 just when Zagrebacka was issuing its €450m debut eurobond, only to hear that the central bank’s obligatory reserve requirement would be applied at a much higher rate.

Zoran Koscak, a board member of Raiffeisen Bank in Zagreb, says: “While the central bank has to try to reduce foreign indebtedness, the technical solutions are all aimed at the funding side and not at the asset side. You limit the demand for corporate loans if you attack the funding side.

“Our margins are being squeezed because of monetary policy. We won’t be allowed to join the EU if the central bank sticks to its current monetary policy,” he warns.

Mr Rohatinski admits that the marginal reserve requirement rate in Croatia is “higher than in any other European country,” but says the central bank has told lenders that it will reduce the general reserve requirement rate in two steps in order “to make it possible to have decent loan growth”.

In January, the central bank trimmed the general rate from 18% to 17% in order to free up domestic funding sources. “The measures have to be kept in place for some time in order to curb inflation and reduce foreign indebtedness. EU accession will result in a reduction of reserve requirements to EU norms,” Mr Rohatinski adds.

A promising market

Yet despite the central bank’s ultra-tight monetary policy, Croatia’s banking market remains attractive to lenders. Several international lenders, including Belgium’s KBC and France’s Société Générale, have signalled their interest in acquiring UniCredit’s stake in Splitska Banka. “Although [banking] penetration is the highest in Croatia, there is still a long way to go to catch up to the European average. There is significant potential for growth, even in the fast-growing mortgage market,” notes Mr Peter.

With a booming tourist industry indirectly accounting for 22% of the country’s GDP, banks are eagerly eyeing the corporate finance market. “There’s a lot of appetite for infrastructure financing and project finance work. We did the first public-private partnership in the highway sector. This is definitely a growth area for us along with asset management,” says Mr Peter.

Zagrebacka is targeting the real estate market. “We are doing deals which 12 month ago I can honestly say were in the realm of science fiction. It’s amazing how the green light from the European Commission [last October for Croatia to begin accession negotiations] has changed things. Property funds are now allowed to get into new types of investments,” says Mr Goldstajn.

Croatia is also experiencing brisk growth in higher-yielding mutual funds. According to research from Raiffeisen, in Croatia, savings in mutual funds only account for about 3% of GDP, compared with 5.3% in Hungary and 46.3% in the eurozone, so the former could experience a boom in mutual funds. “This is the business of the future [in the retail market] after mortgages. The market got going in 2003 and will develop rapidly in our view,” says Mr Koscak.

Lending problems

While Croatian banks’ risk management systems have improved markedly, lenders complain about the legal and regulatory environment for retail lending. “The land registry is a problem for mortgage lending. There are uncertainties about property ownership,” says Mr Peter.

Mr Koscak says: “A credit bureau would certainly help us enormously. It’s in the process of being set up but clients don’t have credit histories so it’s difficult to know if a client has two or three bank accounts.”

Although banks’ margins have tightened significantly because of the central bank’s restrictive monetary policies as well as fierce competition among lenders, banks are offsetting the drop in interest margins by boosting fee and commission income.

“There are three ways to deal with lower spreads: increase lending volumes, repackage loans and do more cross-selling, and we’re doing well on all three fronts,” says Mr Goldstajn.

Mr Rohatinski, who accepts that not all of his policies are popular with the banking industry, says the sector is well prepared for EU accession.

“There are no serious problems as far as the legal and regulatory framework is concerned. The new banking law and the [2001] law on the Croatian National Bank have been revised in order to ensure compliance with EU regulations,” he says. “Our main challenge going forward is to fulfil the Maastricht criteria [for membership of the eurozone]. We already satisfy several of the criteria but must work harder to meet the fiscal criterion [of a budget deficit under 3% of GDP].”

As a euroised economy, Croatia is less at risk from the adverse exchange-rate developments that banking regulators and credit rating agencies have identified as a threat to the stability of the banking systems in Poland and Hungary.

“The majority of deposits are in euros. The kuna has been extremely stable against the euro. The only real exchange-rate risk is connected with the Swiss franc, but most mortgage loans are in euros,” says Mr Peter.