Poland might not be the first country that comes to mind in the context of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). But not only is central and eastern Europe’s largest economy a member of China’s Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, Poland also holds potential for infrastructure investments – especially in the country’s poorly connected east – and sees benefits in the initiative’s wider impact on the Polish economy.

Poland’s Morawiecki Plan, now also known as the Strategy for Responsible Development (SRD), presented by prime minister Mateusz Morawiecki in early 2016 (then still deputy prime minister), highlights one area for potential Chinese investment.

According to the plan, the country seeks to invest more than 1500bn zloty ($436bn) from public funds and about 600bn zloty from private sources in infrastructure and industry projects by 2020 to improve the country’s competitiveness internationally. Yet when the plan was first presented, nearly half of the investments were expected to come from EU funds.

A different approach

“Investors see Poland as a gateway to the EU – as a window for exporters. The EU single market comprises 500 million people, but at the same time, we can finance most [of our projects] on our own or through operational programmes backed by EU funds,” says Krzysztof Senger, executive vice-president at the Polish Investment and Trade Agency. “The Chinese model of investing in Africa and central Asia is not suited for central and eastern Europe – but we invite Chinese companies and investors to look at the different tenders [within Poland].”

While the large availability of EU funds might be limiting the need for Chinese investment in Poland, these funds are expected to decrease with the new EU budget. However, the size of prospective projects could be another constraint to Chinese involvement.

“Poland may be a large country in the region, but from a Chinese perspective it is still relatively small,” says Grzegorz Zielinski, head of Poland and the Baltics at the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development. “You may talk about two multi-billion-dollar projects and you may list two or three slightly smaller projects [which will need financing in the near future] but that would be it in terms of the mega-sized projects [that Chinese investors are typically looking for].”

Infrastructure brings size

One of the SRD initiatives earmarked as potentially attracting the interest of Chinese investors is a so-called 'Central Communication Port'. This hub is to be built around a new airport, which might be located in Stanisławów, 40 kilometres from Warsaw. The proposal is to create a transportation hub combining several forms of transport such as air, rail and road.

The government further seeks to reconstruct several seaports in its quest to turn Poland into a key European logistics centre. A second multi-billion-dollar project, which the government will seek to finance, is the creation of the country’s first nuclear power plant, according to Mr Zielinski.

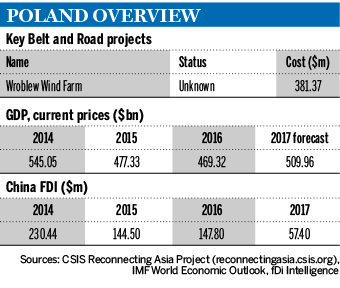

According to greenfield investment monitor fDi Intelligence, annual foreign investment in Poland in 2015 and 2016 was just under $150m each, down from $230m in 2014, and 2017 saw a low of only $57m.

The CSIS Reconnecting Asia Project, which has compiled a list of key BRI project data across the globe, lists one Polish project as being part of China’s initiative: Wróblew Wind Farm, which Luxembourg-registered private equity fund China-CEE Fund acquired in November 2014 and exited in January 2015.

Added benefit

According to Mr Senger of the Polish Investment and Trade Agency, investments made under the BRI in less-developed countries could also bring some added value for the Polish economy.

Poland may be a large country in the region, but from a Chinese perspective it is still relatively small

“The core of the BRI is investment in infrastructure, shipment, roads, etc,” he says. “In terms of global trade, there is a huge opportunity for Polish companies in these countries where this new infrastructure is being built. The prospect of better logistics brings added value for these countries and for prospective exporters from Poland looking to do business there.”

Mr Senger especially highlights potential benefits for Polish businesses looking to export agricultural machinery, pharmaceuticals and processed foods to countries such as Kenya.

And, also at home, Chinese influence is growing: China’s three largest banks by Tier 1 capital – Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, China Construction Bank and Bank of China – have all opened offices in Warsaw to serve Chinese companies and Polish-Chinese trade. So far, Poland is running a large trade deficit with China, which the government is hoping to reduce in the future.

Poland’s development bank, Bank Gospodarstwa Krajowego, is supporting trade finance as well as other areas of development finance including infrastructure and public finances. “Chinese investors take their time and I appreciate that – if you want to build a strong country you have to plan [this] for generations,” says Beata Daszyńska-Muzyczka, president of the management board at Bank Gospodarstwa Krajowego. “I strongly believe that we have a number of areas for co-operation, but we may need some time to build our approach to working together.”