The country has hit a sweet spot in international capital markets and Moscow’s debt is on the verge of usurping sovereign Eurobonds as Russia’s benchmark bond.

Fixed income instruments are playing a central role in financing Russian entities and foreign investors are flooding into Russia, seduced by the combination of high yields and strong rouble appreciation. Domestic issuers are also leaning heavily on the bond market as the only real source of unsecured financing that can tap a growing lake of liquidity, while yield-hungry domestic investors have few other choices. Russian banks are either too small to make big loans or reluctant to take on corporate risk so companies have turned to the bond markets to raise money or soak up surplus petrodollars.

Market recovers

Despite instability in the banking system last summer, Russia’s bond market had fully recovered by the start of this year. Yields on Moscow City’s benchmark 10-year bonds fell below 8% for the first time ever and by April it was issuing bonds with yields a little above 7%. At the end of March there was a sell-off in bond markets at the prospect of US interest hikes. Spreads between US treasury bills and Russia’s longest sovereign bond – the Russia 30s – jumped 35 basis points (bp) in a week.

Analysts say the spreads will widen further if US interest rates continue to climb. International investors will be lured away to safer US instruments while Russian banks are sensitive to the US Federal Reserve’s decisions as they invest incoming petrodollars into the domestic bond market.

“There are a lot of foreign investors on the Russian bond market that follow the exchange rate dynamics closely, but the Russian banks are also quick to arbitrage between rouble and dollar-denominated assets,” says Mr Pakhomov.

Despite these jitters, Russia’s promotion to investment grade by Standard & Poor’s at the start of this year means that the size of issues are getting bigger and maturities longer as investors become more diverse.

Debts are paid

Flush with cash, the Russian government has begun to pay off its international loans. Debts to the World Bank and IMF have already been settled and at the time of writing it looked as if Russia had agreed with the Paris Club to pay off at least some of its $43bn debts early.

With no new sovereign Eurobond issues on the horizon, investors have switched into corporate Eurobonds. However, analysts say the peak demand at the end of last year has passed and the prospects of rising interest rates in the US has dampened appetite for Russian paper.

“This year we won’t see a new wave of issues and those companies that had plans will have to put them on the back burner,” says Pavel Mamai, head of fixed income research at Renaissance Capital.

However, Russia’s ratings upgrade at the end of January caused a surge in interest in the corporate Eurobond, and spreads to Russia’s sovereign bonds narrowed as investors switched, still hungry for high yields. Russian banks, the riskiest of the bonds on offer, benefited the most and the gap with sovereign bonds tightened by more than 100bp in a week following the announcement.

Russia risk

So-called “Russia risk” – shorthand for volatile Kremlin politics – has been reducing steadily in recent years and the country boasts macroeconomic fundamentals to make any Western government envious. But the destruction of oil company Yukos last year left its mark on the bond markets.

“Eurobond prices still reflect some of this Russia-specific risk but I think it is overdone: state company bonds are too expensive and oligarch bonds are underpriced. Investors assume that the government will support state companies if they get in trouble while private companies are open to the Yukos-risk. Both ideas are wrong,” says Mr Mamai. “This year we are expecting to see more demand for the cheaper oligarch companies as calm returns and no new attacks on oligarchs appear.”

Most of Russia’s big companies that want to issue Eurobonds have done so and everyone is waiting for second-tier companies, which are currently issuing lots of rouble bonds, to grow.

“The real boom will come in two or three years’ time when the second-tier companies reach critical mass and can issue Eurobonds. There is a still a huge un-sated demand for cheap long-term financing and if these companies could issue a Eurobond now, they would,” says Mr Mamai.

About two dozen companies are building up their reputations with international investors through credit linked notes (CLNs) – short-term international borrowing that has a low disclosure threshold, a product pioneered by Trust (formerly Trust and Investment Bank). Typically, these notes are between $50m and $100m with maturities of between six months and two years. Their issuers are unabashed about using them as a visiting card during introductions to international bonds investors.

Rouble bonds

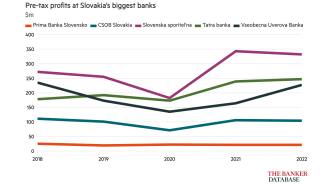

While the Eurobond market is stuck in a holding pattern, the domestic rouble bond market is flying. The growing pool of money, coupled with a strongly appreciating rouble against the dollar, has been driving the market’s growth (see figure 1).

The government is almost certain to miss its 8.5% inflation target this year and finance minister Alexei Kudrin now expects Russia to end the year with inflation at about 10%. At the same time, the flood of petrodollars into the country has driven the yields on Russia’s best rouble bonds to about 8% – negative real interest rates – as buyers of bonds make their money from the rouble’s appreciation.

“Russia’s fixed income markets are now very closely tied into what is happening in the rest of the world. We are a (very small) part of the global market and yields depend on global interest rates and the exchange rate outlook,” says Mr Pakhomov. “But there is too much money in Russia chasing too few quality assets, which is driving down the yields.”

Moscow City is taking advantage of the surplus liquidity to build up its portfolio of bonds. There is already a good supply of shorter-term bonds and the city plans to issue its first 15-year bond in the autumn plus longer-term bonds to “pack out” the longer end of the yield curve between 10 and 15-year maturities with another Rb7.5bn ($278m) of issues this year.

Foreigners return

Foreign investors are back after being hit last year by banking instability and the Central Bank of Russia’s attempts to halt rouble appreciation. The bank abandoned its policy of interfering in exchange rates in October and promised in February to concentrate on controlling inflation at the expense of letting the rouble strengthen. Mr Pakhomov says foreigners now hold about 50% of Russia’s blue-chip rouble bonds and 25% of the second-tier bonds (see figure 2).

US interest rate fears caused a sell-off among foreign investors (predominately hedge funds) but the impact is being steadily diluted since Russia scored a hat trick of investment grade ratings in January as more institutional investors bought into Russia’s bonds.

Mr Pakhomov says an informal head count at a recent fixed income conference revealed that one in five of the big institutional investors already owned Moscow City bonds and another 30% said they were actively thinking about investing.

Still, it’s early days. Russia’s investment grades have opened the door to a new class of investors but many are still doing their due diligence. Foreign investors remain heavily invested in short-term bonds – and Moscow City is still the only rouble bond that has an investment grade – while Russian investors dominate longer-term rouble bonds. The double demand from both Russian and foreign investors for short-term paper means the short end of the yield curve is inverted.

Stability has also been improved by Russia’s big banks increasing their share of bonds following last summer’s mini-bank crisis. The central bank handed out stabilisation loans to state-owned Vneshtorgbank specifically to buy out the debt portfolios of smaller wobbly banks as a way of injecting liquidity into the sector.

While the number of issues is still rising, rouble bonds are becoming more concentrated among the more reliable blue chips as the size of issues rises even faster. For example, the Moscow Region was planning to issue a Rb12bn five-year bond in April that bankers expected to command yield of 8%-9%. In 2001, when the rouble bond market reappeared, issues were typically Rb500m with maturities of 1-2 years and yields of 13%-15%.

Cautious bankers

Still, some bankers worry that Russia’s excess liquidity will cause trouble because there is still too much cash chasing too few quality assets. Rising yields threaten to split the market, pushing less stable banks towards the riskiest bonds.

Most Russian companies that are issuing rouble debt are unrated and as yields fall, the high cost of capital means that smaller banks are turning to increasingly risky junk bonds to maintain their profits. As long as petrodollars continue to flood into Russia, even the most dubious bonds are finding buyers.

“There is plenty of money in the system and banks have a lot of spare cash. They need to invest into something and so demand is high. There should have been some regular defaults but there have been none, despite the fact that some companies are now highly leveraged,” says Mikhail Galkin, deputy head of fixed income at Trust.

A sharp fall in oil prices could trigger defaults but most bankers are unconcerned as most money is in the big liquid bonds and only small banks taking punts on junk bonds will be hurt.

“There were serious concerns about beer-maker PIT’s ability to pay when it launched a second bond only two days before its first Rb1.5bn bond matured in March,” says one fixed income trader involved in the issue. “But the high yield of 14.25% was too tempting and investors still bought it. People see the yield and continue to play the pyramid game – who will be the last one out when the shock comes?”