Russia is back in the market – or is it? After four months of inactivity in the Russian Eurobond market, Alfa Bank and Sberbank broke the drought in June 2014, and the Russian equity market rebounded from the 26% slump in prices in the first quarter of 2014, but recent events have once again cast a shadow of doubt over the market.

First, on July 16, a fresh round of sanctions were imposed on Russia by the US. Then, the following day, a Malaysian Airlines airplane was brought down over a disputed region in eastern Ukraine, killing all 298 on board, raising tensions between pro-Russian separatists and the Ukrainian authorities, and leading to calls for further sanctions on Russia.

Editor's choice

Fresh sanctions

The mid-July round of sanctions imposed by the US caught many by surprise, as the restrictions were, for the first time, extended to companies with outstanding bonds and equity, as state-owned oil company Rosneft, private natural gas company Novatek, and state-owned lenders Vnesheconombank and Gazprombank were all added to the list.

Gazprombank was one of the five banks that took advantage of the open bond market between late June and early July. But, as the US sanctions do not cover equity and bonds that have already been issued, they will not impact holders of Gazprombank’s €1bn five-year bonds, which were sold on June 26. The sanctions also exclude short-term debt of up to 90 days.

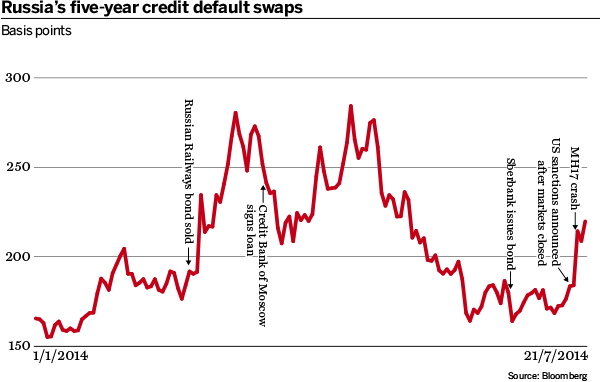

The market’s surprise at the sanctions was clearly visible; five-year credit-default swap (CDS) contracts to insure against a default of the Russian sovereign rose by 30 basis points (bps) to close to 214bps on July 17. Levels rose to a close of 220bps on Monday, July 21, but have not yet reached the April 25 peak of 284bps.

Turbulent year

The problems in Russia's capital markets date back to the end of February 2014, when pro-Russian forces annexed Crimea. With mounting tensions, the first talk of possible sanctions on Russia threw an unknown variable into the equation for all parties involved in the country's financial markets.

“In March and April, the regulators came into pretty much every large fund manager in the US and the UK and asked: 'What is your exposure to Russia?',” says Charlie Robertson, global chief economist at Russian investment firm Renaissance Capital. “Compliance teams got very anxious.”

The initial sanctions imposed by both the US and Europe, as well as those added by the US in mid-July, do not apply to the whole Russian community, as is the case with US sanctions in Iran, but they target specific individuals and organisations. Recent events have caused politicians to call for further action.

As it stands, the reaction across many Western asset management institutions has been to strongly reduce their exposure to Russia. Aberdeen Asset Management’s emerging markets fixed-income team switched its position on Russia from overweight to underweight in early March – not due to visits from regulators, but with a view on their end investors, according to Viktor Szabo, a portfolio manager at the company.

“The switch to underweight was a drag on our performance but we thought that’s more prudent vis-à-vis our clients than being overexposed to a country that is going into a serious geo-political crisis,” says Mr Szabo. “On the local currency side, Russia is close to 10% of the index. Hence, being completely out means taking huge active risk against the index.”

Window of opportunity

Things had calmed down by late June and early July. Russian CDS spreads, which had spiked to 284bps on April 25, had come down to 164bps by June 24. This, and the tightening of secondary spreads, allowed the primary market to end the four-month issuance break, with the first Russian bonds coming in June.

“When the crisis was at its peak, investors were questioning capital markets access of Russia Inc,” says Nick Darrant, head of emerging markets in the central and eastern Europe, Middle East and Africa debt syndicate at French lender BNP Paribas. “The fact that Sberbank has proven [that a Russian company is able to issue] was very significant.”

On June 23, Sberbank, the largest Russian bank, became the first Russian issuer to sell a benchmark Eurobond since Russian Railways’ €500m nine-year transaction on February 27. Its €1bn five-and-a-half-year deal was its first euro-denominated issue, and it came in line with its dollar curve to yield 3.4%.

The decision to issue in euros rather than dollars was purely related to Sberbank’s pricing expectations, according to Anton Karamzin, senior vice-president at Sberbank. “We issue a few billion dollars equivalent a year but, up until now, the euro market hadn’t been displaying enough price leniency or depth in demand, but we unexpectedly saw some good conditions in this market,” he says. “We are totally not sensitive to volume and timing, but are driven by price. At 3.35% for five-and-a-half years, if you swap that into our dollar curve on the day of closing, we virtually paid zero new issue premium.”

And, despite the transaction’s euro-denomination, Sberbank had “some good American demand through the European arms” for the transaction, too, Mr Karamzin adds.

More to come?

Sberbank’s bond followed the smaller, €350m three-year transaction by Alfa Bank’s holding company, ABH Financial Limited, sold in early June. Alfa Bank and Sberbank’s bonds were followed by Gazprombank’s euro issue and VTB Capital’s Swiss franc-denominated bond.

Promsvyazbank, the last firm to make the issuance window, was the only Russian company to sell a dollar-denominated and subordinated bond – at 10.5% for seven years – which it got away just one day before the sanctions struck. All the new issues have since sold off, with Promsvyazbank’s notes trading at a yield of 11% on July 21.

More higher yielding products out of Russia could emerge should the situation between Russia and Ukraine stabilise, purely for economic reasons, says Tamer Amara, partner at law firm Clifford Chance in Moscow. “Russian banks need to bolster their capital,” he says “So we expect there to be greater demand for capital-linked bond offerings – subordinated capital and Tier 1 capital – because of the introduction of Basel III requirements in Russia and because of greater regulatory capital charges for consumer finance banks introduced by the Russian central bank. And, given the suppressed demand for this type of instrument, we may see more of this later this year.”

Volatility strikes

In the equity market, the Russia Trading System Index (RTSI) crashed to a low of 1064 on March 14, due to overall outflows from emerging market assets in January as well as Russia-specific issues, and rebounded to 1421 as of June 24 – the index started the year at 1443. The equity market was also hit by the events of July, which chopped 113 points off the RTSI in six days. It closed at 1239 on July 21.

“There was passive money coming back into the Russian market and, it is fair to say, that there was more Russian money playing actively in Russian stocks,” Laurent Cassin, head of equity capital markets for northern and central Europe and Russia at French lender Société Générale, said, before the new sanctions were announced.

Trading volumes for the London and Moscow stock exchanges show that, even before the worst of the Ukrainian crisis, as early as December 2013, Russian investors were putting money to work domestically, as depicted by the narrowing gap between the average liquidity at the two exchanges, which stayed close throughout the difficult months of March and April.

Mr Robertson at Renaissance Capital says that he was not surprised to see the rebound in the equity market because prices can only fall so much. “If you look at price to earnings [PE] ratios of equity markets in central and eastern European emerging markets, then Russia’s forward-looking PE is at 5%,” he says. “The next cheapest emerging market is at 9%, which is China. At a time when global asset prices are high, it is often the very cheap stuff that moves the most and that’s Russia.”

He believes, however, that the crisis will take 5% to 10% in value off Russian asset prices for the next five years.

Delayed, not cancelled

From a primary perspective, equity capital market bankers have been asking themselves whether the booming environment for initial public offerings (IPOs) was going to suffer as a result of the growing hostility between Russia and Ukraine.

Equity capital markets witnessed a buoyant start to the year, with some $200bn raised in the first six months of 2014. For Russian companies, the sweet spot was again in June. Payments service provider Qiwi was the first to market with a primary transaction, a $319m secondary public offering, on June 16. This was followed by a $473m privatisation block trade by stock exchange Micex.

The pipeline includes deals for Credit Bank of Moscow and Promsvyazbank, as well as privatisation-related transactions for firms including Russian Helicopters and VTB Bank, but the timing of these will all depend on market sentiment. As of July 21, there have been no new IPOs out of Russia.

“This semester, we have completed deals for Polish, Czech and Romanian issuers so there is absolutely no reason, apart from this blip, why we should not have completed Russian deals,” says Mr Cassin. “We were working on [Russian] deals that were supposed to be completed in the first half of the year and when the crisis came we thought they would get cancelled, but they were just postponed.”

Sanctions language

Compared to the bond and the equity market, the loan market’s reaction to the political situation has been slower off the mark, with the outbreak of the crisis failing to have an immediate impact on lending, after a very liquid start to the year.

Credit Bank of Moscow was one borrower that got its deal away early. The $500m syndicated loan agreement with one-year and 18-month tenors – its largest ever – was prepared before the outbreak of geo-political tensions, and was not disrupted by them. It was signed, oversubscribed, on March 26.

“Where terms were settled before the outbreak of hostilities, lending banks still sought to deliver on commercial loan agreements,” says Quentin L’Helias, head of structured finance for the Europe, Middle East and Africa loan syndicate at Société Générale. “From April onwards, we were able to witness a gradual reduction in the number of banks still pursuing deals.”

Nobody publicly announced a decision to pull out of Russia, it was more the case of banks taking the necessary time to understand the situation and decide which precautions were needed to be added to loan documents.

“There has been a real tension between what the banks felt they needed to have to comply with regulations and what borrowers were prepared to give and take as risk from a commercial perspective to make it worth them doing the loan,” says Logan Wright, managing partner in the Moscow office of Clifford Chance.

“The key thing for banks lending was to secure a way of getting their money back and exiting the loan if they find themselves suddenly with a sanctioned borrower because they don’t want to wind up in breach of regulations or offside with the regulators. For a borrower, that’s not very desirable. You go through all the trouble of getting a loan together, pay the arrangement fees, you borrow the money and find you have to pay it back again, in a hurry and in a lump sum and arranging alternative financing is not going to be easy."

Mr Wright adds: “That has now settled a lot more. The relative risk allocation is much better understood and accepted on both sides.”

Risk factor

Even with the new sanctions language, the business of lending to Russian institutions has still been impacted by the political crisis. Many foreign banks were already focusing only on their tier-one clients, and with the introduction of sanctions those deals that were in progress took longer to get signed, closed with smaller volumes and, in some cases, even changed denomination from dollars to euros, according to Mr Wright.

Société Générale's Mr L’Helias says: “It is a market [at the moment] that is pricing liquidity and not risk. As the number of deals, and therefore banks signing into them, increases, we will see market standards develop around the concept [of sanctions language], in turn providing borrowers and lenders with more confidence in what the market can deliver. This holds true as long as no new sanctions are announced.”

All in all, the financing situation in Russia is not quite as bad as many anticipated when the first talk of sanctions hit the news desks, notes Renaissance Capital’s Mr Robertson.

“Yes lending fell and yes the markets were closed for Russia for a few months but you can go back to late-2011 or to 2009 and [related to general risk aversion] lending was pretty low then, too,” he says. “But, what actually was odd, was the high level of lending 12 to 18 months ago. Then, Rosneft bought out TNK from BP, a massive purchase that caused a spike in lending and therefore year-on-year comparisons earlier this year look like suddenly no one is lending to Russia.”

This analysis not only relates to lending. Russian companies also had a record year in terms of bond issues in 2013, while a weak economy this year is not spurring investment. All in all, companies have required less funding in 2014.

Eastward bound

At the same time, there is one other, entirely different development happening. Unwilling to rely on the sentiment of Western investors, Russian companies are looking for new opportunities in the East.

“In the middle of the whole situation, there was guidance by the [Russian] government to look at Asian markets to explore the possibility of finding an open market if the West ever closes for Russian companies,” says Société Générale's Mr Cassin.

Gazprom was the first to react. The largely state-owned gas company, which was already listed on the stock exchanges in Moscow and St Petersburg, through American depository receipts in London, Berlin, Frankfurt, and on the over-the-counter market in New York, added an additional listing for its global depositary receipts (GDRs) in Singapore. The GDRs were included in the Singapore exchange listings from June 17, but so far there are no indications of strong Asian demand.

“A listing is a tool to reach investors,” says Mr Cassin. “With a listing in London you can reach pretty much everybody. With a US listing you have access to a lot of US domestic funds that may not be allowed to invest outside of the US. If you’re listing in Asia, then you’re hoping to attract Asian investors not allowed to invest outside of Asia.”

To what extent Asian money is available to Russian companies remains to be seen. In the case of aluminium company Rusal, for example, which initially only opted for a dual listing in Hong Kong and Paris in 2010, there was no clear evidence that Asian money was rushing to invest at the time, according to Mr Cassin.

But, should the Asia strategy pay off, an additional listing for Russian companies in the East could cause liquidity in the West to dry up in the long term, and leave another unpleasant aftertaste for investors in that part of the world.