The bank bail-out in Cyprus is small in comparison with the overall eurozone crisis, involving about €10bn to re-capitalise the commercial and co-operative banks, plus sovereign support of about €7bn.

Editor's choice

More on Cyprus

More on eurozone crisis

So the decision to bail-in insured bank deposits of under €100,000 came as a surprise to the markets, which had been working on the assumption the EU would not risk contagion to raise the comparatively small sum of €5.8bn.

“Playing with fire”, “politically damaging” and “irresponsible” were some of the initial reactions from analysts to the plan for a special one-off levy of 6.75% on insured deposits of less than €100,000 and 9.9% on deposits more than €100,000.

Confidence shaken

At time of The Banker going to press, the deal had yet to be finalised, with the Cyprus Parliament delaying a planned vote until March 19, 2013. Even if significant changes are made to the plan, though, confidence in the safety of eurozone deposits has already been shaken.

The raid on deposits affects all Cypriot banks, though the main focus of the bail-out is the two largest commercial banks, the Bank of Cyprus and Laiki Bank Group, with some capital set aside for smaller commercial banks, plus about €2bn for the co-operative banking sector, which plays an important role in the Cypriot economy.

The Bank of Cyprus is the dominant player, with total assets of €36bn as of September 30, 2012. Full-year earnings to December for Bank of Cyprus were due on February 28, but it chose not to publish preliminary results as the diagnostic exercise commissioned by the steering committee to assess the bank's capital needs had not been finalised and communicated to the bank. Cyprus Popular Bank, the operating unit of Laiki Bank Group, also postponed its preliminary 2012 results.

In the broader context of the rolling eurozone crisis the amounts involved are small, and the EU might have been tempted simply to pay up and move on to problems in bigger eurozone countries.

Germany’s influence

However, there is an election approaching in Germany on September 22 and with political parties jockeying for advantage, there was pressure not to be seen to be letting Cyprus off too lightly.

It is not an abstract debate; the Greece and Cyprus crises have become a regular theme for the tabloid newspapers, including the mass circulation Bild Zeitung, which is closely monitored by politicians in Berlin to take the temperature of the electorate.

The commonly expressed view in Germany on Greece during their bail-out talks was that the Greeks need to work harder. For Cyprus, it is that it remains a centre not only of tax avoidance, but also tax evasion and money laundering, with Russians the main culprits.

Certainly the ties with Russian corporates and wealthy individuals have grown close over the past 20 years, because Cyprus has promoted itself as an international business and financial centre.

To take one example, in May 2012 the director of the Cypriot Inland Revenue Department, George Poufos, was one of the speakers at a seminar in Moscow sponsored by the Bank of Cyprus. It was entitled: “Russian and Cypriot opportunities in an ever-evolving tax environment.”

However, the way in which EU officials and German politicians like to highlight the close ties with Russia angers many Cypriots. Indeed, outgoing president Dimitris Christofias, in a farewell address in Brussels on February 8, said he was bitter at what he regarded as persecution over allegations of Russian money laundering.

The so-called troika of the European Commission, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the European Central Bank want to see austerity measures as a condition for a bail-out. It also wants to see tighter control over the financial sector, especially as future economic growth in Cyprus is expected to be underpinned by financial services.

European consequences

The troika’s approach to the bank bail-out was subject to intense debate, in what one analyst calls the muddiest eurozone crisis so far. Possibilities discussed included haircuts on senior debt issued by the banks. Hitherto no senior bank bondholders have been burned anywhere in the eurozone crisis, all the way from the Anglo Irish Bank in 2009 to Dutch bank SNS Reaal in early 2013. Rating agencies, too, warned the so-called bail-in of senior bank bondholders would negatively affect the way in which they assess the strength of banks throughout Europe.

Cypriot banks are heavily reliant on deposits though and with few senior bonds outstanding, a haircut would not have produced very much compared with the near €6bn to be realised by the levy on deposits.

Thus haircuts on junior bank debt plus deposits was the chosen route. “There was a serious discussion about a haircut for senior bank bondholders and fortunately this has been avoided,” says Dr Holger Schmieding, chief economist at Berenberg Bank. “The European Central Bank had argued against the idea, since it could spark contagion.”

Mr Schmieding continues: “The area where Germany did get its way was to insist on haircuts for bank deposits, which unfortunately could set a destabilising precedent for banking systems elsewhere in the eurozone. Germany also insisted on raising corporate tax rates.”

Moody’s responded by publishing a commentary on March 18 saying the Cyprus bail-out was credit negative for bank depositors across Europe.

“In previous bank rescues, we have seen subordinated debt and hybrids bailed-in to the private sector involvement process,” notes Bridget Gandy, managing director, financial institutions, at Fitch Ratings in London. “Imposing a levy on depositors of banks in Cyprus is a new way of doing things. While it addresses some of the concerns about using EU taxpayers‘ money to support Russian deposits in the Cyprus banking system, there is a risk that depositors in banks elsewhere will be quick to withdraw their funds when they see their country under financial pressure.“

Debt sustainability

One of the key elements of a bail-out plan is a debt sustainability analysis, with a target of debt at less than 120% of gross domestic product (GDP) by 2020. Above that level, the IMF will find it difficult to sign up to the programme.

As with all long-term forecasts, small changes to assumptions, such as annual GDP growth, will have a big impact over time. Gabriel Sterne, an economist at investment bank Exotix in London, is concerned that, with bank deleveraging and a tough austerity package being pushed through, projections on GDP growth and debt sustainability are unlikely to be met. “We think over-optimistic GDP projections will form a centrepiece of the troika programme and at the outset this is likely to facilitate disbursement,” he says.

Exotix has argued all along for a large upfront recapitalisation, sufficient to allow the banks to continue to make new business loans. "We would insist Bank of Cyprus maintains a well-funded unit for this purpose, to prevent a Greek-like credit choke," says Mr Sterne.

Certainly, the Bank of Cyprus has a key role to play in stimulating economic growth. It is the largest bank, but has been suffering from poor asset quality in a struggling economy. Late in December last year, the Bank of Cyprus put out a profits warning, saying the group's results after tax, but before the impairment charges on Greek government bonds for 2012, were expected to be much worse than 2011.

Economic deterioration

The deterioration in performance is mainly caused by increased provisions for impairment of loans, as a result of the continuing deteriorating economic conditions and the adoption of stricter assumptions under review by money manager Pimco, as well as reduced operating income. The bank suggested core Tier 1 capital could be below 5% at year-end 2012.

The second major bank is Laiki Bank Group, which has undergone various mergers and re-organisations over the past decade, including the merger of the groups of Marfin, Egnatia and Laiki. The bank is more than 100 years old, and in the 1960s took the name Cyprus Popular Bank. It trades under this name in Cyprus, as part of the Laiki Bank Group.

Laiki’s total assets surpassed €43bn in 2010, overtaking the Bank of Cyprus, but it has since fallen back into second place. Last year, the group took a €2.3bn hit on holdings of Greek government bonds.

Hellenic Bank is smaller and in better shape, and it did press ahead with announcing its 2012 full-year earnings on February 28. Its junior debt, though, has also been bailed-in to the recapitalisation process.

Hellenic’s underlying performance was resilient in 2012, with a total net income of €318m before impairments, although loan loss provisions increased to €162m. As at year-end, the non-performing loan ratio to gross loans stood at 13.3% for Cyprus and 52.1% for Greece. Hellenic saw its deposits rise by 9% year-on-year, to €7.1bn in Cyprus and €615m in Greece. By country of customer, 33% of its deposits are held by Russians.

The assumption is that Russian customers make up a disproportionate percentage of accounts holding in excess of €100,000 and the decision to impose the levy was quickly condemned by the Russian government.

Examining the books

As with other eurozone crises, an outside expert has been looking through the bank books, which has led to some inevitable clashes with bank management.

When announcing on February 28 the delay in publishing its preliminary results for 2012, the Bank of Cyprus noted: “The bank has repeatedly expressed its disagreement to the Central Bank of Cyprus and ministry of finance regarding the assumptions and the methodology of the diagnostic exercise.”

Independent analysis, though, is a crucial part of creating confidence for the EU countries bankrolling the rescue. A clampdown on alleged money laundering, with more transparency in the banking system, is a key demand.

"There needs to be some independent analysis of assets on the bank balance sheets, so it is important that the troika has Pimco looking at the Cypriot banks," says Stefan Nedialkov, an analyst at Citigroup in London. "There was a similar approach with BlackRock Solutions in Ireland and Roland Berger together with Oliver Wyman in Spain."

Mr Nedialkov goes on: "If Germany is to sign off on the bail-out, regardless of whether it is channelled via the troika, European Stability Mechanism or some other mechanism, the Germans will want a close examination of the Cypriot banking system and assurances that it will be brought to EU standards. Over the past few years, Germany has shown that there has to be a clear quid pro quo – we give you the money and you push through austerity and fix your problems."

The Cyprus election result was seen as positive for the troika as its preferred candidate comfortably won the run-off vote held on February 24. Nicos Anastasiades is someone the EU and IMF feel comfortable dealing with, and he argued for a quick bail-out deal with accompanying austerity measures.

There are many observers, though, who feel an important red line has been crossed with the move towards a levy on deposits. As Société Générale said in a note published on March 18, the so-called stability levy risks producing anything but what its name suggests.

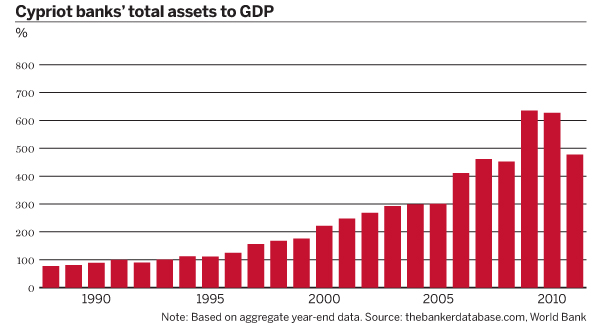

Richard McGuire, a senior fixed-income strategist at Rabobank, expressed concern about the implications of hitting bank deposits thus: “In the contagion stakes Cyprus [which accounts for just 0.2% of eurozone GDP] has clear potential to punch far above its weight.”