Few have benefited as much from Angola’s decade-long oil boom as the country's banks. Their rise has been startling. Having held just $3bn of assets in 2003, in the wake of the country’s destructive civil war, the banking sector had total assets of about $45bn at the end of 2011. It is now the fifth biggest banking industry in Africa, behind only those in South Africa, Egypt, Morocco and Nigeria.

Editor's choice

Banks’ profits have also been spectacular. The nine Angolan lenders in The Banker Database’s latest African rankings made aggregate returns on assets of 3.3% in 2010, one of the highest levels on the continent. And many of them made returns on equity of more than 35%. “Any visitor to Angola today can see the fast pace of modernisation under way, and the financial sector has been capable of responding efficiently to the country’s robust economic and social growth,” says José Reino da Costa, chief executive of Millennium Angola, which is controlled by Portugal’s BCP.

And the rise of Angolan banks is unlikely to slow soon. Economic growth is forecast to be 11% in real terms in 2012 and average roughly 8% to 10% over the next five years. Emídio Pinheiro, head of BFA, Angola’s third largest bank by assets and a joint venture between local telecoms firm Unitel and Portugal’s Banco BPI, says he expects his firm’s asset base to rise about seven percentage points above the rate of economic expansion.

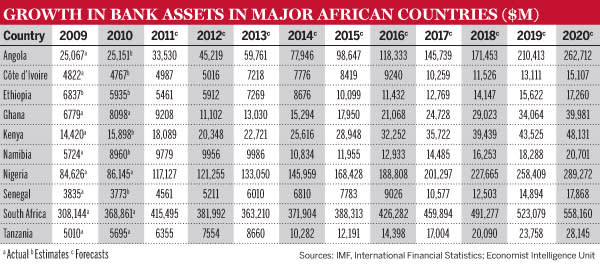

As such, the Economist Intelligence Unit believes that Angola’s banking sector will grow faster than any other in sub-Saharan Africa in the next decade. In a survey last year it stated that banking assets in the country would grow to between $128bn and $263bn by 2020, depending on the level of financial deepening that takes place, particularly the rate at which the unbanked population is brought into the system. At the higher range, Angola’s banking sector would be almost the same size as that of Nigeria’s by that time.

New oil law

A major development occurred at the beginning of May this year, when a new foreign exchange (FX) law for the oil industry was enforced. This requires producers of crude to pay their sub-contractors through the local banking system. Before, due partly to strict capital controls, payments to service providers were made through offshore banks, bypassing local ones altogether. Analysts say the change could double the $30bn of deposits held with Angolan lenders. It will also lead to them having to process far bigger transactions that what they are used to.

“The oil industry in Angola is mostly offshore, which means the investment requirements for all the major producers are huge,” says Pedro Coelho, managing director of Standard Bank Angola, a subsidiary of the South African lender. “So there’s a lot of cashflow between them and their suppliers.”

The government brought in the new regulation to help shore up the country’s FX reserves and also because it felt that local banks had grown big enough to cope with carrying out payments for oil companies.

There has been some unease, however. A few oil firms initially lobbied against the proposal, saying that onshore banks were not yet ready to handle payments on the scale of those in the industry. “The oil law is the single most important piece of legislation for the banking sector [in recent years],” says Anthony Lopes-Pinto, head of Imara Securities Angola, a corporate advisory firm. “The concerns have been around the capacity of the local banks and the integrity of their internal systems. A lot have had problems making big payments.”

Angolan banks admit that the law will have a big impact on their operations, but they say they have spent plenty of time preparing and improving their internal payment systems. “It will be a challenge for the banks,” says Mr Pinheiro. “But if everything goes OK, it should enhance the banking system.”

More taxes

Angola’s banks will also have to adapt to paying higher taxes. Until recently, the government was largely happy to live off royalties from the oil sector. As a result, banks have been able to avoid paying high taxes. The six largest banks in the country paid effective tax rates of just 12% in 2010, according to Imara.

But as they look to diversify the economy and leave it less vulnerable to a crash in oil prices, policy-makers want to increases tax revenues from other businesses. New measures such as taxing local holders of government bonds, which form a large proportion of Angolan banks’ assets, will squeeze their income. “The game is changing,” says Mr Lopes-Pinto. “Treasury bills are now being taxed, which they weren’t before. So a lot of banks are having to think outside the box and be more innovative.”

Competition is becoming fiercer too. Angola already has 23 commercial lenders, which bankers say is a lot for an economy of its size. But several foreign banks are likely to enter the market in the next few years. Standard Bank is currently the only one operating in the country from outside Portugal, Angola's former colonial ruler, many of whose banks have stakes in local lenders. Among those that have applied for licences or who are considering doing so are Standard Chartered, pan-African firm Ecobank, Nigeria’s United Bank for Africa and FirstRand of South Africa.

Although the application process is long – Standard Bank was only granted a licence in 2009 after applying in 2006 – the government is trying to speed it up. The main obstacle is usually the requirement for lenders to take on local equity partners (Standard Bank will own 51% of its subsidiary, and an Angolan entity the rest). But provided this is overcome, official say they are keen to see more foreign banks in the country.

Foreign lenders will mostly look to tap the corporate banking market, at least initially. Mr Coelho says Standard Bank will firstly target the bigger Angolan companies, not least those in the oil sector. It will then move on to the suppliers of those firms, often small and medium-sized enterprise (SMEs), before eventually trying to tap their employers to build a retail banking business. “We want to take it step by step,” he says.

More lending

Angola’s private sector companies will welcome the arrival of more foreign firms. They struggle to access funding from local lenders, most of whom have small loan books and loan-to-deposit ratios (LTDs) of less than 60%. Yet as treasury bills become taxed and their profit levels are squeezed by more competition, analysts say it is inevitable that banks will look to lend more.

Bankers in Angola say their exposure to the private sector is low because of the country’s unsophisticated business environment and collateral being hard to come by. The recent establishment of a credit bureau will help rectify this and ensure that banks can grow their books without non-performing loans rising much above 5%, which is the sector average.

Some banks are already trying to make headway in the SME sector. Millennium Angola recently started offering ‘SME packs’, which include basic services such as current accounts and treasury management advice but are different depending on which sector a company is in. “Because Angola is a nation being rebuilt, there are significant opportunities in almost every activity,” says Mr da Costa.

Other bankers admit that the industry as a whole needs to lend more to the private sector. “The credit environment is not that positive,” says Mr Pinheiro of BFA, which has a LTD ratio of only about 30%. “But things have been moving very fast. We are not that aggressive yet. But we are revising our strategy as we think there will be lots of opportunities in the coming years. The credit market will grow.”

One of the barriers to the credit market’s development is the dollarisation of the Angolan economy. Thanks to the influx of oil money in the past 10 years, almost all goods can be bought in dollars. And about half of banks’ deposit bases are made up of dollar accounts, while dollar lending is often more popular than that in kwanzas, for which interest rates are typically between 15% and 25%. “We want to lend in kwanzas, but people don’t want to borrow in kwanzas,” says Mr Pinheiro.

Lower interest rates would help, and they may be on the way. Inflation fell to 11.4% at the end of last year, the lowest level in memory. The central bank is confident of bringing it down to single digits by next year.

Untapped retail market

The retail market has developed significantly in the past eight years. The use of debit and credit cards has risen rapidly. Less than 250,000 Angolans owned them in 2004, whereas five years later 2.8 million did, according a recent survey by accountancy firm KPMG. And the number of ATMs rose 10-fold in that period. “The banking system has gone through huge developments in the past few years,” says Pedro Calixto, a partner at consultancy PricewaterhouseCoopers in Luanda, Angola's capital. “It is much better than it was. Until about 2006, we had no ATMs. If you wanted money, you’d have to queue at a bank. Now ATMs are everywhere and you can also use credit cards.”

Yet the retail market, which made up only about one-fifth of banks’ revenues as recently as two years ago, remains largely unexploited. Angola’s unbanked population is thought to be 80% to 85%. Lenders are trying to boost their retail revenues by quickly growing their branch networks, especially outside Luanda. Mobile banking is also being introduced, although it is still basic in Angola, with account holders only able to get balance updates and a list of their previous few transactions via text messages. But bankers say it will not be long before they are able to carry out transactions and deposit money via their mobiles, as is the case in countries such as Kenya.

Angolan banks are attractive investment targets for foreigners. Portuguese lenders have reaped big profits from their stakes in local institutions. But given the absence of an Angolan stock market, portfolio investors have little chance of gaining exposure to the banking sector. This could change once a long-mooted stock exchange is finally launched, something bankers hope will happen by the end of 2013.

Banks would initially make up the bulk of the BVDA (Bolsa de Valores e Derivados de Angola), as the exchange will be known. Mr Lopes-Pinto of Imara says many of them have already stated their interest in listing, including Millennium Angola, Banco Privado Atlântico and Banco BIC. Banco Bai, Angola's largest lender with more than $8bn of assets, would also be among the first to go public, investors believe. Partly in preparation for this, most large Angolan banks now release results quarterly and in English as well as Portuguese.

Mr Lopes-Pinto believes that the largest five banks, who control 80% of Angola’s market, would each have capitalisations of more than $1bn.

Not yet mature

The emergence of a stock exchange would also help Angolan banks by deepening the local debt market (as government securities would be listed on it). Mr Coelho of Standard Bank says the development of a proper yield curve for treasuries is necessary in the long term, it will boost liquidity in the market and allow banks to use such instruments for repo transactions. At present, an interbank market, despite the central bank’s recent establishment of a Luanda interbank offered rate (Luibor), is all but non-existent beyond a small amount of overnight lending. “There are still many steps to be taken before Angola’s banking industry can be called mature,” says Mr Coelho. “Many things need to be created to guarantee that the market has enough liquidity. This will help reduce the role of the central bank in providing that liquidity.”

Angola’s banks are well capitalised, well regulated and highly profitable. And the sector as a whole will inevitably grow quickly in the next decade. But the banks that emerge the strongest will not be those that simply ride the wave of economic growth. With higher taxes, particularly on treasuries, and more competition from foreign lenders looming, Angola’s banks will have to be more innovative. Although bigger than most of their African peers, their models are a lot less sophisticated. Lending more to the private sector will be one way of changing this. Other measures would include doing more to tap Angola’s unbanked masses.

Some banks could even consider acquisitions. After all, with the market highly concentrated and the top five lenders having an 80% share, banks outside that group could struggle over the coming decade. Big balance sheets will be an important factor in determining which lenders manage to thrive and which merely survive.