If students of global banking are looking for a lesson on counter-cyclical regulation, then Israel might be a suitable case study. During the US and European property booms that turned to bust in 2008, Israeli real estate prices and rents were declining slightly. Since 2008, Israeli real estate has soared by about 60%. Only one of the top five Israeli banks, Bank Hapoalim, suffered a loss due to financial market exposure in 2008, and all have since remained profitable.

The Bank of Israel (BoI), which houses the country’s banking supervision agency, has never been shy about calling the shots – it explicitly called for the departure of Hapoalim’s chairman in 2009 after its losses the previous year. As house prices rose, the regulator intervened. Loan-to-value ratios on mortgages are now capped at 75% for first-time buyers, 70% for other owner-occupiers and 50% for buy-to-let investors. The risk weighting assigned to mortgages was hiked to 50% for most mortgages, about five times higher than in many European countries. If the loan-to-value ratio exceeds 60%, the risk weighting on the mortgage is 100%.

Profit pressure

This is all very prudent, but it inevitably puts pressure on bank profit margins. And corporate lending has also been under the microscope. Ownership in the Israeli economy is highly concentrated among a dozen or so large holding companies with interests across a wide range of sectors, including stakes in some of the banks themselves.

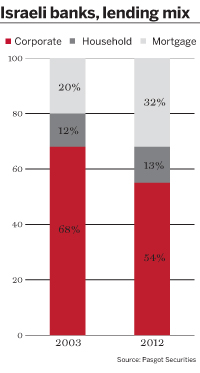

These holding companies had become highly indebted in recent years – corporate debt peaked at almost 110% of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2007, compared with just 37% for household debt at the time. A number of high-profile holding companies such as Delek, Elbit, IDB and Elran were forced to engage in debt restructuring negotiations, and regulators naturally encouraged banks to cut concentration risks in their portfolios. In June 2013, the finance committee of Israel’s Knesset (parliament) approved a draft Business Concentration Law that would limit cross-holdings between financial and non-financial companies. Corporate debt is now down to less than 90% of GDP, while the switch to retail banking has seen household debt climb to a still modest 42%.

“The biggest banks shed exposure to large corporates and moved into SMEs [small and medium enterprises] and especially mortgages. But now those lines are slowing too, due to the counter-cyclical measures. Domestic demand is also slowing, which will hit SMEs and push up credit card arrears,” says Terence Klingman, head of research at Israeli investment fund manager Psagot Securities.

The new capital requirements on mortgages, and the international target of a 9% core Tier 1 capital adequacy ratio, mean that most Israeli banks cannot expand their assets aggressively until they have built capital. Yet most of the Israeli banking market is well penetrated, and consolidated. The top five banks have an 85% market share, and the top two – Hapoalim and Bank Leumi – control about 60% of the market between them.

“There is pressure on interest margins, and fees are tightly regulated and so very transparent, which also makes them very competitive. That makes it difficult to grow incomes without growing balance sheets, so right now cost control is key,” says Mr Klingman.

Turnaround story

Yair Seroussi, a former finance ministry official who later set up Morgan Stanley’s office in Israel, was appointed chairman of Bank Hapoalim after the BoI’s intervention in 2009. After his appointment, he looked for areas where Hapoalim was underperforming its overall market share of 32%. The bank decided to focus on the mid-market segment, where it had a market share of only 24%, compared with 40% for large corporates.

As part of the plan, the bank initiated a special Hapoalim Growth Fund for supporting small businesses, with reduced fees on its loan products, totalling NIS300m ($83m). Since the switch toward SMEs, Hapoalim has cut exposure to the concentrated holding groups by a quarter. The mid-market share has now risen to 32% at the expense of Hapoalim’s competitors.

“We are finding good clients, good industries, many export-led companies. When we are focused, we have the best execution in the market – that was my main surprise when I came to the bank, it was the discipline that allowed us to change very quickly. And I made this my personal undertaking, visiting clients with the marketing teams, because I think it is strategically important to have more of these middle-market companies who will be tomorrow’s large corporates,” says Mr Seroussi.

His team also identified two key demographic elements among retail customers. The first was the Arab population in the Galilee region in the north of the country, where education levels have risen dramatically. Hapoalim expects incomes to follow in due course, and the bank has doubled branches in the region. The second group is among the ultra-orthodox Jewish community. The current government has begun cutting welfare provision to ultra-orthodox Jews who do not work, encouraging more of this segment to enter employment. A growing proportion of the community’s women are also continuing their education to degree level and entering work.

Radical change

The second wave of changes that Mr Seroussi initiated focuses on cost control and efficiency. Banks are heavily unionised in Israel and wages had previously been based on a so-called 'autopilot' arrangement, rising 4% to 5% per year regardless of results. Staff costs are typically more than 60% of total expenditures, and cost-to-income ratios in Israel are mostly not much less than 70%, high by international standards.

Mr Seroussi’s response was radical, and it won union approval in 2012. The autopilot was ended, but the wage structure was also redistributed on a one-off basis, with a 5% cut for senior management, a pay freeze for middle managers and a 6% rise for junior staff.

“Thanks to our flexible union agreement, we are able to make fast decisions, and there is an energy in the bank because we have made people feel it is their own business – about 8% of the ideas in our strategic plan come directly from staff in the field,” says Mr Seroussi.

The bank also embarked on a technical overhaul to boost efficiency, hiring Zvi Naggan, a senior executive at Israeli technology company Amdocs, as head of technology in January 2011. Hapoalim developed software to allow mid-sized businesses to run all their banking operations through an iPad, but Mr Seroussi says there is no intention to eliminate the branch network. Instead, the bank has used technology to take back-office business out of branches and improve branch efficiency with a lean branch model.

New thinking needed

Bank Leumi was less exposed to the financial crisis, and overtook Hapoalim as the country’s largest bank by assets in 2008. Arguably, this may have reduced the sense of urgency to keep updating the business model. In 2012, just as chief executive Galia Maor retired after 17 years at the helm, Leumi slipped back behind Hapoalim on assets. Leumi’s profits for 2012 were only half those of its rival. This was partly due to one-off factors – including a provision for NIS340m in response to US investigations into tax evasion by Leumi clients in the US. But chairman David Brodet fully recognises the need to focus on cost control, and on what he calls “defining and understanding the new customer better”.

In response to social protests that swept Israel in 2011, sparked in particular by resentment among young people at the sharp rises in the cost of housing and living, Leumi began offering a purely digital bank account. Reflecting the needs of the younger customer base, this account has a more limited range of functions than a branch-based account, and in return charges no fees. Leumi is also leading the way with applications such as online and smartphone share trading.

Taking a leaf from Hapoalim, Leumi hired Dan Yerushalmi, a senior executive from Amdocs, to become its head of operations and information systems in November 2012. In fact, Leumi now seems to be treading a similar path to the one its rival took a couple of years earlier, including the development of a leaner branch model. Leumi was more exposed to large corporates, at about 60% of the total portfolio. This has now been reduced to 49%, and the bank is targeting 40%. SMEs have been the major element of this strategic switch. In May 2013, the bank initiated a Leumi Business Fund featuring low-fee credit – albeit 10 times the size of Hapoalim’s fund at launch, with NIS3bn.

Different strategies

One area where Leumi clearly differs from Hapoalim is in its approach to cost control. Leumi has retained a 5% annual wage rise, but has made 800 redundancies while transferring or relocating another 2000 staff internally, out of a workforce of more than 13,000. There is also an early and voluntary redundancy scheme.

“We are turning over every stone to find how to cut costs. We have focused on more efficient procurement and logistics to reduce the operating budget, and the transfer of back-office functions out of the branches has released real estate for other uses. Our efficiency ratio is already improving, and we should see the improvements maturing in 2014,” says Mr Brodet.

Leumi has also taken a more active stance on the mortgage market. Hapoalim’s market share in mortgages is underweight at about 22%, and Mr Seroussi says the bank is not actively marketing mortgages to new customers. Instead, it has launched a publicity campaign entitled 'your home bank' to encourage existing customers to stay with Hapoalim for their mortgage.

By contrast, Leumi is pushing harder in the mortgage sector to help reduce the large corporate component of its portfolio, and its market share rose from 24% in the first quarter of 2012, to 27% in the first quarter of 2013. Mr Brodet believes fundamentals will keep the real estate market underpinned.

“The supply of new properties is slow because of the pace of government land releases and municipal zoning rules, but the population is growing by 1.8% annually, so Israel needs at least 40,000 to 45,000 new units every year. The demand for mortgages is high and we cannot satisfy all the applications that we are getting,” he says.

Fast mover

The retail market has also been the major focus for Mizrahi Tefahot, the second-tier bank that is by some distance Israel’s fastest growing and most profitable, with a return on equity three or four percentage points above Hapoalim. In the past decade, Mizrahi’s market share has doubled to 16% across loans and deposits, taking the bank to third place in many products – although Israel Discount Bank is narrowly larger in terms of balance sheet size.

“Our focus on retail and basic banking back in 2004 seems perfectly sensible now, but I remember at the time that many people were surprised because other banks were focused on corporate banking and the securities business,” says Eldad Fresher, Mizrahi’s chief financial officer who was confirmed in June 2013 as the next chief executive following the retirement of Eliezer Yones.

Mr Fresher attributes Mizrahi’s success to the dynamic culture fostered by a targeted hiring policy. The bank has the youngest and best-educated workforce in the industry, with the most even gender balance. The youth of its team also helps keep costs down, with the cost-to-income ratio less than 60% in the first quarter of 2013. The bank also has a distinctive approach to technology and online banking.

“Our concept is live virtual banking and branches. We want a platform that will bring customers closer, not push them away, something digital but personalised,” says Mr Fresher.

Counter-cyclical thinking

While Leumi has recently discovered the attractions of low-cost services for cash-strapped customers, Mizrahi bought Bank Yahav in 2007 and transformed it into a specialised retail lender offering a limited service and product range with the lowest fee structure of any Israeli bank. Mr Fresher is keeping a close eye on house prices, but is satisfied with the bank’s risk management. The debt service burden for Mizrahi mortgages is less than 30% of monthly incomes, and he is confident there is still room for growth in this sector.

“With 1.8% population growth and natural customer churn, there is a pool of 4% to 5% new uncommitted customers on the market every year, and we can win them without aggressive competition because we have better customer segmentation and more personalised products,” he says.

Intriguingly, Mr Fresher also sees an opportunity to improve penetration and margins by picking up some of the corporate clients whose credit limits are being cut back by their current relationship banks that are over-exposed to large corporates. Corporate lending currently accounts for less than 30% of Mizrahi’s total portfolio.

“We are cautious because the economy is running below capacity, but we can provide solutions to these clients even with a conservative risk appetite,” says Mr Fresher. His plan is to increase the share of corporate lending in Mizrahi’s portfolio to 35% by 2017. If it pays off, this strategy would be another win for counter-cyclical thinking.