When Mozambique ended its devastating 15-year civil war in 1992, it was widely condemned as being a basket case. Today, the south-east African country is viewed as one of the continent’s brightest prospects. Although still very poor, with a per capita gross domestic product (GDP) of less than $700, its economy has risen almost 10-fold since fighting ended. Inflation has fallen from 16% to just 3% in the past three years.

Editor's choice

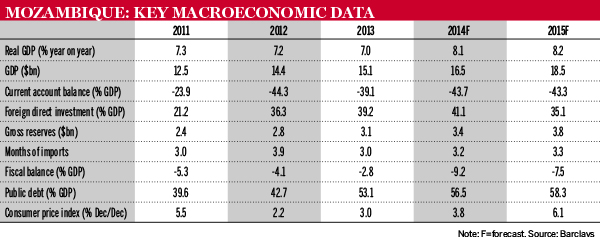

Most of the growth has been down to Mozambique’s so-called mega projects, such as its Mozal aluminium smelter, and small amounts of gas extraction in the south. But recent discoveries of huge coal reserves in Tete province and offshore gas fields in the north have caused foreign direct investment to soar. GDP rose 7% last year and is forecast by the International Monetary Fund to increase 8% annually until 2019.

“There’s a lot of interest in Mozambique,” says Antonio Coutinho, head of Standard Bank Mozambique, the country’s third largest lender by assets. “Before, you’d go to the US and no one would want to speak to you. You couldn’t get an appointment if you tried. Now, you’re quite popular. People want to understand what’s going on.”

Making moves

Coal exports began in 2011, and the government hopes that production, mainly carried out by Brazil’s Vale and Anglo-Australian company Rio Tinto, will reach 40 million tonnes by 2017.

Gas production in the northern Rovuma basin will have the biggest impact on the country, however. Mozambique is expected to start selling liquefied natural gas (LNG) to Asia in 2019 or 2020. Such is the scale of its deposits that US firm Anadarko, which along with Italy’s Eni is leading exploration activities, believes it will become the world’s third largest LNG exporter in the next decade.

For an economy with an output of just $17bn annually, the gains will be substantial, allowing Mozambique to reduce its dependence on aid, which funds about 40% of the country's budget, and cut poverty. “The composition of our economy and trade should change dramatically in the next decade,” says Valige Tauabo of Cabo Delgado em Movimento, which lobbies on behalf of communities living near mega projects.

But Mozambique faces plenty of challenges. Thanks to the dire state of its infrastructure, much of which was destroyed in the war, coal production has so far disappointed. Vale’s local subsidiary made a loss of $480m last year as it struggled to get coal from the interior to the coast. It is spending billions of dollars rebuilding railway lines from Tete to the ports of Beira and Nacala.

Right management

In the gas sector, implementing an effective tax regime will be crucial. The original mega projects generated little revenue for the government, which says it needed incentives to lure investment so soon after the war. Politicians are working on a fiscal law for LNG, which they hope will strike a better balance between encouraging investment and generating taxes.

Analysts say the new mega projects will only be sustainable in the long term if Mozambicans benefit in the form of better healthcare, education and social services. “If there’s a perception that all the profits are being used at a central government level in a way that isn’t transparent, it will create a lot of discontent,” says Markus Weimer, an independent consultant specialising in Portuguese-speaking Africa. “People need to see real results.”

Mozambique’s manufacturing base is small. The government wants a portion of the gas reserves sold locally, rather than exported, to boost domestic energy supplies and encourage industrialisation, especially since the upstream hydrocarbon industry will generate few jobs for locals, the vast majority of which lack formal employment.

Pedro Coutinho, head of the Mozambican arm of investment bank Eaglestone, says it would be sensible to produce gas by-products, which include fertiliser, paint and plastic, locally. This would diversify the country’s export base. “Instead of just selling LNG, they should also sell refined products,” he says. “If they can industrialise, they can produce a lot of things needed in the rest of the world. You could start a chain of development from that backbone.”

Without economic diversification, Mozambique will leave itself vulnerable to falling global demand for commodities, say bankers. A slump in coal prices since 2011 has already given the government a taste of the dangers. “There’s a risk if our exports are too concentrated,” says Omar Mithá, an independent consultant and former chief economist at Millennium bim, the largest Mozambican bank. “If something happens to prices, it could have a sudden negative impact. That’s what happened in Botswana when diamond prices fell [in late 2008].

“We are not isolated anymore. Anything that happens outside Mozambique could have an impact on the country.”

Scaling up

Although foreign investment in natural resources and infrastructure is driving much of the economy’s growth, other sectors are rising quickly. Many financial companies are booming, in part due to them starting from a low base. “The financial system could grow at a rate of between 15% and 20% [over the medium term],” says João Figueiredo, chief executive of Banco Único, a lender established in mid-2011 and which already has $300m of assets. “We still have a lot of the economy sitting outside the formal system. It’s a question of bringing informal businesses and unbanked people into the formal economy,” he adds.

Others key industries the government is trying to boost include tourism and agriculture. The latter makes up roughly one-quarter of GDP and employs 75% of the workforce. But it is unproductive and mostly consists of subsistence farmers using outdated methods. The United Nations' Food and Agriculture Organisation estimates that Mozambican cereal yields are one-fifth of those in South Africa and one-quarter of Zambia’s.

Policy-makers will have to improve the business environment if they want to see more commercialisation of agriculture and the development of other labour-intensive sectors. Mozambique is generally perceived as being more open to investors than its fellow Lusophone state Angola. But it ranked 137th out of 148 in the World Economic Forum’s latest Global Competitiveness Report, with businesses suffering most from corruption, a lack of access to financing and bureaucracy.

Officials admit to problems, but say a major factor is that Mozambique, because of its recent conflict, has little experience of private enterprise. “This is the first generation we’ve had of businessmen,” says Ernesto Gove, the central bank governor.

Mozambique has mostly been stable since 1992. Yet, last year political tensions rose as Renamo, the main opposition party and the side that fought the ruling Frelimo during the war, carried out sporadic attacks in rural areas against police outposts and government buildings. It also boycotted municipal elections in November. The situation has since calmed down. Analysts are confident that general elections this October, which Frelimo is expected to win, will be more or less peaceful.

If so, Mozambique’s standing among global investors will be enhanced even further. Nonetheless, the country will not be able to rest on its laurels. Deep structural reforms will be needed for years to come if it is to make the most of its newfound riches.