UniCredit chief executive Jean Pierre Mustier compares his overhaul of the Italian bank to running a marathon: the first third has been completed, but there is still a long way to go and the last few kilometres are the most difficult.

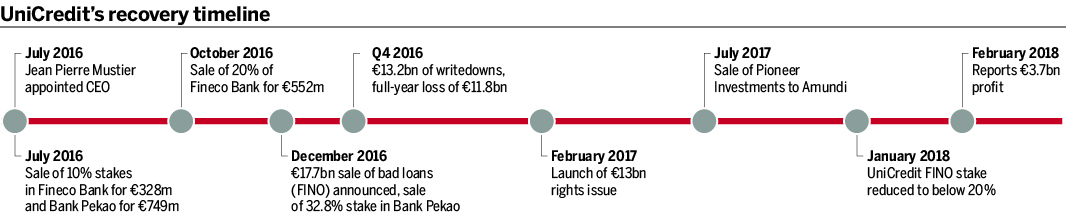

This means keeping up the furious pace that he has set for the bank since taking over as CEO in July 2016. The strategy is ambitious, but analysts are feeling more confident that the bank will pass the finishing line since the release of fourth-quarter and financial year results in February 2018.

The headline of the 2017 results’ press release states boldly: ‘UniCredit: Transform 2019 first year successfully completed, all targets achieved. Strong underlying performance.’ Transform 2019 is UniCredit’s three-year business plan.

On the results front, the bank turned in an adjusted net profit for financial year 2017 of €3.7bn, compared with a loss of €11.8bn the previous year when UniCredit took writedowns on its portfolio of bad loans. In the fourth quarter of 2016, the bank reported losses of €13.6bn after taking €13.2bn in a one-off charge related to the sale of €17.7bn of bad loans, as well as making contributions to an Italian fund for troubled banks. Its core equity Tier 1 (CET1) capital at that time was 7.54%, which left it below European Central Bank targets.

Hitting the road

But what a difference a year makes. Mr Mustier, having started his marathon with bold moves in asset sales and writedowns, followed up with a dramatic €13bn rights issue in February 2017, done at a steep 38% discount to the theoretical ex-rights issue price. He and his chief financial officer, Mirko Bianchi, travelled about 100,000 kilometres in a month or so to generate support for the issue.

Having sold the bank’s private jet as part of a cost-cutting exercise, the two executives performed this task in an appropriately austere manner using public transport and avoiding expensive restaurants. As UniCredit had burned through the €14.5bn cash raised in three previous exercises, they knew that it was vitally important to strike the right tone. The project was codenamed Elkette, which has since become an emblem for the bank.

In an interview at UniCredit’s London offices (see video on thebanker.com), Mr Mustier says: “We are in the first year of a three-year plan and, if you compare our plan to a marathon, it is only the first 14 kilometres and we know that in a marathon the last few kilometres are the most difficult ones. So we are very happy about the first year in terms of the turnaround. In terms of client reaction to what we have been doing, turning around the network and restructuring did not impact our commercial dynamics, which is very positive. We managed to reduce our costs by 4% and to sell down a lot of our non-performing loan [NPL] exposure.”

With the first stage of the marathon completed, UniCredit now has a fully loaded CET1 ratio of 13.6%, return on tangible equity of 7.2% and gross non-performing exposures (NPE) down to 10.2%. While these last two figures may not seem too exciting, they must be seen in the context of an Italian banking crisis that has put large numbers of NPEs on balance sheets and that has threatened, at times, to destabilise the entire eurozone.

Healing process

S&P Global Ratings estimates that at the peak of the crisis, in the third quarter of 2015, total Italian NPEs were €350bn. They have since been brought down to €275bn, amounting to 17% of customer loans, with only about half covered by provisions. The agency expects the stock to fall to €200bn, or 13% of customer loans, by 2019.

Against this background, S&P released a report in January entitled ‘Italian banks will continue to heal in 2018’. “Italian banks are looking healthier now than they have for the past few years,” says the report. “Private sector creditworthiness has improved and banks’ efforts to repair their balance sheets have paid off, to the extent that we now expect a return to some moderate profitability in 2018. Institutions have been strengthening their capital, bolstering loan-loss reserves, reducing their stocks of NPEs and cutting costs.”

This, then, is the context for Mr Mustier’s marathon. A former head of corporate and investment banking at Société Générale, the Frenchman joined UniCredit as the head of its investment bank in 2011 but quit in late 2014, apparently unhappy with the strategic direction.

The answer to this problem was for him to take charge of that direction as CEO. But he took the helm at a time of extreme pressure on the bank. In mid-2016 UniCredit had €80bn in bad debts, its share price had fallen by two-thirds in the space of a year (although it has since made a partial recovery) and was trading at less than one-quarter of book value. Former CEO Federico Ghizzoni had stepped down two months earlier amid investor discontent. The bank’s problems had arisen as a combination of its takeover of Italian bank Capitalia in 2006, the global financial crisis and continuing recession and economic problems in Italy.

A simple plan

Mr Mustier talks often about his aim to make UniCedit “a simple pan-European commercial bank”. It has operations in Germany, Austria, central and eastern Europe as well as Italy.

To achieve his goal, Mr Mustier has been simplifying the bank by selling assets; by streamlining operations through branch closures, a reduction in headcount and reducing the complexity of legacy IT; and by taking strong measures to deal with bad loans. He has also improved corporate governance by making changes to the way the board is nominated.

The bad loans part of the marathon began with the €17.7bn bad loan securitisation under the project code FINO – which stands for ‘failure is not an option’ – a phrase coined by group chief risk officer TJ Lim, who has played a key role in working out the bad assets. US institutional investors Pimco and Fortress bought half the deal, with the UniCredit stake later reduced to below 20% through further sales to Italian insurer Generali, King Street Capital Management and Fortress.

Unlike Italian rival Intesa Sanpaolo, UniCredit opted for securitisation sales and disposals rather than in-house recoveries. “For us, reducing the bad loan portfolio allows us to reduce the risk profile and to reduce the cost of capital, so our shareholders are much better off if we sell the loans,” says Mr Mustier. “Of course, we are going to give away, potentially, the profit that we can earn on these loans, but the shareholders will recover [this] in terms of share price appreciation and because our cost of capital goes down.

“With our capital increase last year we raised €13bn, and it was also important to show to the market that our loans were properly marked [valued]. We did this large transaction of €17bn which covered a lot of asset classes and we could tell the market, ‘look, we have proper [valuations] because our loans are provisioned to sell’.”

Maximum capacity

Francesca Vasciminno, senior director, financial institutions, for Fitch Ratings, says: “Asset quality is still affecting the ratings of Italian banks and UniCredit is no exception, but we are seeing progress in dealing with the problem. There has been a reduction in the stock of NPLs achieved with the help of a €17.7bn securitisation of these loans and the sale of more than 80% of the securitisation, among other measures.

“Italian banks have taken different approaches to solving their NPL problem. Intesa Sanpaolo has strong income generation and capital flexibility and chose to go down the ordinary workout path, whereas UniCredit decided to have a large capital increase and NPL securitisation. In doing this UniCredit showed it had good capacity to access the capital markets.”

Mr Mustier was able to hit the ground running in asset sales because his predecessor, Mr Ghizzoni, had already arranged to sell down stakes in the online broker FinecoBank and the Polish operation Bank Pekao. This gave a €1bn boost to Mr Mustier’s capital raising efforts within weeks of him starting the job. The rest of UniCredit’s Pekao stake was sold in December 2016, followed in 2017 by the very significant sale of Pioneer Investments to French asset manager Amundi for $3.55bn. The two companies agreed a 10-year deal to continue distributing Pioneer’s products through UniCredit’s branches.

“We sold our asset management activities to Amundi, which created the largest asset management [player] in Europe,” says Mr Mustier. “The underlying strategy is that we keep, of course, all the ability to generate the commissions by selling the product, so our network gets exactly the same revenues and has an extended product range thanks to the Amundi Pioneer [combination].

“We keep the income generated by the network, and we sell the product factory and we don’t get the revenues of the product factory. With asset management, my conviction is that the product factories will be under more and more pressure in terms of economies of scale. To lower the cost per asset under management, you need scale. Organically, we could not reach this scale so [we achieved instead] the best of [both] worlds. We get the fee income on one side and we don’t have the exposure and the compression of margin on the other side.”

Analysts criticised the sale of the Fineco stake as contrary to the bank’s desire to push digital and online. Mr Mustier says the rationale was to limit the size of the capital increase, and that in future UniCredit will more likely be buyers rather than sellers of Fineco.

Target practice

Key to UniCredit’s more positive reception from shareholders is Mr Mustier’s setting of targets and his track record of either hitting or beating them. In December 2017 he told investors that he was increasing the gross NPE reduction target by another €4bn by the end of 2019, the new target being €40.3bn. He also said the 2019 financial year dividend payout would rise from 20% to 30%, and to 50% beyond 2019. The bank’s non-core assets will be fully run down by 2025.

But despite this progress, UniCredit will still be a bank with high NPEs compared with European averages and, some would say, a not very demanding 2019 return on equity target of 9% (up from 7.2% currently).

For his part, Mr Mustier stresses the distinction between the core bank (the part that will stay) and the non-core, that will be run off.

“[The reason] we are selling down NPLs is actually to reduce our cost of capital,” he says. “We think that profitability of banks on average is not going to be much higher than single digit and so it is really important to lower the cost of capital.

“But if you look at the bank, it is important to look at the stated figures and we have an objective of 9% return on equity, but at the same time the core bank – meaning the bank outside the non-core portfolio, which will be fully run off by 2025 on a self-funding basis – this quarter had a return on equity at 9.1%, which is higher than the stated figure of 7.22%. All in all we are very comfortable with the underlying business of the bank, and to be able to reach the 9% and to lower our cost of capital to single digits as well.”

The digital imperative

The same distinction between core and non-core can be made with NPLs. “If you look at our core bank, our NPL exposure to total loan ratio is below 5% – it’s 4.9% – which is very close to the European Banking Authority average,” says Mr Mustier. “The stated figure is 10.2% but as I said [the high ratio] is coming from the non-core and we are running off the non-core to zero by 2025.”

While addressing historic problems, Mr Mustier is also focusing on the digital transformation that is essential for a modern bank. “To keep fit, it is very important that we are challenged and so by cannibalising the business model, by disrupting it, we can actually find a better offer to the clients and other opportunities to make money,” he says. “So with Apple Pay on one side, Alipay on the other, we actually improve our revenues and our profitability.”

But what about external disruptors such as market volatility and the Italian elections in March? Could they push the UniCredit runners off course?

“Temporarily the markets are correcting, which I think is a healthy correction,” says Mr Mustier. “We do not believe the Italian election will change much in terms of Italy’s commitment to Europe and the ability to progress on some of the reforms. So, in fact, we think that the environment is relatively positive. For Europe, it’s the first time for many, many years that we have synchronised growth and, at the same time, Italy turned a corner last year with the bailing out of some of the banks – thanks to the government policy – so the risk premium for Italian banks or the financial sector has been going down.”