In a keynote speech on the sidelines of September’s Sibos conference in London, the recently appointed chairman of the Hellenic Bank Association, George Handjinicolaou, said that, after 10 long years: “The Greek financial sector has emerged from its challenges, and is moving steadily, confidently – but also swiftly – into a new era of stability and growth, ready to finance the increasingly attractive prospects of the Greek economy.”

It was an optimist vision, but Mr Handjinicolaou is not alone in hoping that 2019 will be the beginning of a new period of growth for the Greek financial sector, and for the country's economy in general.

A year of change

Greece exited its last bailout programme in August 2018, in a significant milestone for the country as it looked to get its economy back on track after almost a decade of economic misery. Between 2010 and 2013, Greece’s economy contracted by one-quarter, and then stagnated for another three years. Unemployment skyrocketed, and the Greek government had to turn to the EU and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for aid, with the country ultimately receiving bail-outs worth €289bn.

Greece’s economy has recently been showing signs of recovery, albeit cautious ones. In 2018, the country’s real gross domestic product (GDP) grew by 1.9%, up from 1.5% in 2017. The unemployment rate dropped to 17% in June 2019, down from a peak of about 28% in 2013, but remains the highest in the eurozone. And while the international rating agencies have upgraded the country’s sovereign rating, it still lacks an investment grade rating.

“The recovery of the Greek economy continues at a steady pace despite the global downturn,” says Dimitris Malliaropulos, chief economist and director of economic analysis and research at Bank of Greece, the country's central bank. He points out that the 0.8% quarter-on-quarter growth in GDP in the second quarter of 2019 was likely the fastest rate among eurozone countries.

“The positive momentum is expected to continue as the investment climate improves and growth-friendly economic policies gain traction,” adds Mr Malliaropulos. “Nevertheless, higher and sustainable growth rates require the end of banks’ deleveraging. This will need to be backed by a comprehensive transfer of bad loans from bank balance sheets, combined with private debt restructuring.”

Post-election developments

Greece’s general public debt grew to 181.1% of GDP in 2018, up from 176.2% in 2017. However, overall debt would have declined by 2.9 percentage points if it had not been for efforts to build up the country’s cash reserves. These exceeded €24bn at the end of the first quarter of 2019, enough to cover estimated state debt financing needs until at least 2022.

Without its bailouts, Greece is now relying on the bond markets to refinance its debt. In February 2019, the government successfully issued a five-year bond, and the following month it issued a 10-year bond worth €2.5bn, at a yield of 3.5% – a further sign of returning confidence in the economy.

Since July 2019, Greece has had a new government, headed by the centre-right New Democracy party. It has reassured the markets that it is committed to business-friendly policies that can attract the investment necessary for Greece’s economic recovery. “We think an important development is on the politics side,” says Michele Napolitano, head of western European sovereigns at Fitch Ratings. “There was a smooth post-election outcome, and for the first time in 10 years there is a single-party majority in Greece, so we are looking at a more politically stable backdrop.”

He points out that following the previous elections in 2015, Greece was on the verge of potentially exiting the euro. Within weeks of the 2019 elections, the Greek government had already issued a seven-year bond at a historically low yield. “In our view, the government is making the right sounds, and it is also taking some important steps,” says Mr Napolitano, adding that one of the first things the new government did was to bring the policy portfolio of the banking sector and the privatisation policy portfolio under the responsibility of individual ministries. “In the past, these two very important portfolios were shared across different ministries,” he says. “You can already see after only a few months that policy implementation is swifter in these two areas.”

QE possibilities

In late September, European Central Bank president Mario Draghi told the European Parliament’s committee on economic affairs that Greece could be included in the next round of its quantitative easing (QE) programme, if it continues to make progress in implementing reforms.

“I’m pretty confident that if things continue to move in this way and the progress continues to be significant on the path of reform, there will be conditions that Greece can participate in QE, but progress has to be made, [it] has to continue,” he said.

Greece has also committed to meeting a 3.5%-of-GDP primary budget surplus for each of the years up to 2022, excluding debt servicing costs, with the target then dropping to 2.2% of GDP. However, in a statement in late September, the IMF suggested that the government and its European partners build consensus around a lower primary balance path, “given ample economic slack, critical unmet social spending and investment needs and to accommodate spending that would create synergies with stepped up reforms”.

It added that much of the needed structural transformation of the Greek economy still lies ahead, and that fixing the banking sector, “currently a misfiring engine of growth”, is a top priority.

Misfiring or streamlining?

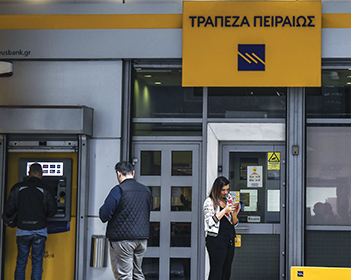

The number of domestic credit institutions operating in Greece has fallen from 35 to just 15 since 2009, with the four systemic banks – Eurobank, Alpha Bank, Piraeus Bank and National Bank of Greece (NBG) – accounting for about 96% of banking sector assets.

According to the central bank, the operating income of Greek commercial banks and banking groups was €7.89bn in 2018, down 5.7% year on year, with losses after tax of €81m. However, the latter was a considerable improvement on 2017, when losses after tax came to €474m. Losses related to discontinued operations also showed a steady decline, amounting to €431m in 2018, down from €570m in 2017 and €2.9bn in 2016. The capital adequacy ratios of the four systemic banks have remained strong, averaging 15.9% at the end of 2018.

Deposits have been gradually returning to the banking sector: private sector bank deposits rose for the sixth successive month in August 2019, according to central bank data, with business and household deposits up from €138.64bn to €139.72bn. “Deposit inflows have accelerated in the first seven months of 2019 and, importantly, the dismissal of capital controls since September 1 has not changed this dynamic,” says Bank of Greece’s Mr Malliaropulos.

It is estimated that between the start of 2016 and the end of August 2019, close to €24bn of private deposits returned to the Greek banking sector.

At the same time, banks operating in Greece are targeting quite aggressive cost cutting as part of their new business plans, according to Jonas Scorza Floriani, director of research at investment banking institution AXIA Ventures Group, with staff and branch networks likely to be further reduced. The number of people employed in the Greek banking sector has dropped significantly since 2010, with staff down 38% to just under 40,000 and total branches halving to 1979 over that period.

Bad loans

Greek banks are still working hard to reduce their exposures to bad loans. As of December 2018, non-performing exposures (NPE) in the Greek banking sector totalled €81.8bn, 46.7% of the total loan book and the highest rate in the eurozone. However, this was down from a peak of €107.2bn in March 2016. Banks ultimately aim to reduce their non-performing loan (NPL) ratios to below 20% by the end of 2021.

Alpha Bank, the country’s fourth largest lender, reduced its NPL ratio to 32.7% during the second quarter of 2019, in line with the average pace of previous quarters. In May, Paul Mylonas, chief executive of second largest lender NBG, told a news conference his bank aims to reduce its NPL portfolio to about 5% of total loans by 2022, from 41% at the end of 2018. Part of this involves selling three soured loan portfolios by the end of 2019.

“The consistent decrease of NPEs reinforces the argument that overall credit risk at the system level has decreased compared with previous years and that further rapid deceleration is now becoming crucial,” says Nikolaos Georgikopoulos, visiting research professor at New York University’s Stern School of Business and a senior financial adviser to the governor of the Greek region of Attica.

Mr Georgikopoulos believes the need for systemic solutions has clearly been understood by policy-makers and the markets, pointing to the Asset Protection Scheme for NPEs. Approved by the European Commission in October, this aims to assist banks in securitising and moving NPLs off their balance sheets. However, he adds that the government should also develop a more comprehensive, ambitious and well-coordinated strategy to fully restore asset quality, along with the quality and levels of bank capital, liquidity and profitability.

ELA no more

One key development in 2019 is that Greece’s largest banks no longer rely on the more expensive emergency liquidity assistance (ELA), drawn from the central bank. ELA levels peaked at €86.8bn in June 2015, but had dropped to about €1bn at the end of 2018. Since then, both Eurobank and Alpha Bank have fully repaid their ELA balances, joining NBG and Piraeus Bank, which cleared theirs in 2017 and 2018, respectively.

The removal of emergency borrowing is expected to improve depositors’ confidence, while allowing banks to strengthen their balance sheets. “The repayment of the ELA will enhance Greek banks' efforts to diversify their funding mix. Without their dependence on ELA, and given the sustainable improvement in liquidity conditions, Greek banks will likely attract greater interest from international unsecured bond investors,” ratings agency Moody’s said in an April credit outlook report.

At the beginning of September, Greece also finally lifted its remaining capital controls (established in June 2015 when banks were seeing a rapid outflow of funds). Initially, banks had placed a €60-per-day cap on cash machine withdrawals, and while this was lifted in October 2018, limits on money transfers abroad had remained in place. The end of capital controls was important symbolically as well as practically. “It marks a return to normality and growing confidence,” Bank of Greece governor Yannis Stournaras told Reuters at the time.

Lending growth

New lending reported by Greek banks shows signs of promise, according to AXIA’s Mr Floriani. “In 2019, the expectation for the full year is that the volumes of new loans are 30% to 40% above the volumes achieved in 2018,” he says. However, new lending is still “not enough to offset the repayments and not enough to offset the decrease in NPLs”, he adds. “Hopefully, once the bulk of the reductions is over, the only change in the loan book will be new lending versus repayments. There should be a normal functioning market in Greece in a few years’ time.”

Private sector financing actually decreased by 1.1% year on year in 2018, to €170.3bn from €183.9bn, according to the Hellenic Bank Association, with the pace of repayments, write-offs and disposals exceeding new loan demand. Greek banks have contributed to the country's economic recovery mainly through the funding of large-scale infrastructure projects and the ongoing funding of the tourism industry, it added.

Even so, confidence is returning. The national housing market has continued to show signs of recovery, with prices increasing at their strongest pace in more than 12 years in the second quarter of 2019, according to the central bank, with the uptrend seen in all market segments. In February, Greek banks reached a new deal with the government on a framework to protect borrowers from home foreclosures.

Clouds on the horizon

Despite signs of recovery, Greece’s economy remains at risk in the event of a significant global downturn. The collapse of UK tour operator Thomas Cook in September 2019 came as a stark reminder. The tour giant brought about 3 million tourists to Greece in 2018 – 9% of total visitors – and Moody's Investors Service described its collapse as credit-negative for Greek as well as Bulgarian and Cypriot banks, because of how it will weaken the cash flow of businesses operating in tourism and related sectors. As of June, bank lending to non-financial corporations operating in the accommodation and food services sectors accounted for 10.8% of total loans in Greece, making them key sectors.

Furthermore, Bank of Greece’s Mr Malliaropulos suggests that the window of opportunity for Greece narrows as the global economy weakens, “making the recovery of the Greek economy a race against time”. He adds: “Economic policy must act quickly and effectively to put the economy on a sustainable growth path before the next global downturn materialises.”

Time will tell if the measures already enacted, together with those being developed, will adequately cushion the Greek banking sector, and the economy as a whole.