When the Icelandic government began winding up the three largest banks in the country in October 2008, it was the most comprehensive collapse ever seen in such a large banking system. Total assets were estimated at about $160bn at the end of 2007, and the three banks that dominated the system, Landsbanki, Glitnir and Kaupthing, all fell in a single week.

Editor's choice

Under emergency legislation enacted in October 2008 and April 2009, the three banks’ domestic assets and liabilities were transferred to new banks – Landsbankinn, Islandsbanki and Arion Bank. These new banks are majority-owned by the three defaulted banks, effectively giving the original foreign creditors a debt-for-equity swap. For the foreign assets and liabilities, three resolution committees were appointed to assess claims from creditors and depositors, and to run down the banks’ loan books and investments.

Close scrutiny

The results of this approach are closely watched. Several banks in Spain, Portugal and Greece either failed or only narrowly passed the EU stress tests in July 2011. Their prospects for raising extra capital are dim, and any sovereign restructurings will only damage their balance sheets further. Moreover, markets for their domestic assets, especially real estate, have shut down, making it impossible to value assets accurately.

“In that situation, you can only consider creating non-bank asset management structures that require no capital and can manage the assets while they wait for markets to recover to realise something closer to economic value. That frees up the operating banks to get back to lending to the economy, and I do not see any resolution to the crisis in southern Europe without such an exercise,” says Nils Melngailis, recently appointed a co-head of the European financial services group at restructuring advisor Alvarez & Marsal.

And he should know. His firm is currently advising Kaupthing, and he was previously the recovery CEO for Latvian bank Parex, appointed after its collapse and government rescue in 2008.

No choice

What is certain is that the refusal to bail out the Icelandic banks was a necessity, not a choice. The government at first attempted to recapitalise the banks, offering Glitnir equity of 84bn Icelandic krona ($600m at the prevailing exchange rate) in September 2008.

However, the Central Bank of Iceland could not cope with the withdrawals from Iceland’s banks. Foreign currency deposits in Icelandic banks were four times the size of the central bank’s foreign exchange reserves, and total bank liabilities were more than eight times gross domestic product (GDP). The country sought emergency assistance from the International Monetary Fund and the US and EU governments, but none was forthcoming on the scale required.

In this context, putting the banks into insolvency was the only viable solution. This ultimately protected the creditworthiness of the sovereign. In June 2011, while the governments of Ireland and several southern EU states were still frozen out of international capital markets, Iceland launched a $1bn sovereign Eurobond.

This was its first foray into the international market since the financial crisis. For Icelandic minister of economic affairs Arni Pall Arnason, it was a clear indication that there is renewed market confidence in the finances of the Icelandic government, which is rated investment grade, unlike those of Greece, Portugal or Ireland.

“The success of the bond issuance was a very welcome sign of understanding that there was logic in the way we chose, it illustrates that we are on the right track,” says Mr Arnason.

Massive challenge

But while bailing in the banks may have saved foreign exchange reserves, the fate of the financial sector itself is still far from resolved. The Icelandic district and supreme courts are awash with litigation between creditors, the three banks and the government.

Foreign investors who found themselves participating in one or more insolvency processes in a jurisdiction that has never managed bankruptcies on this scale were forced to contend with unpredictable judicial interpretation, scarce expertise, and a government that was rewriting the insolvency regime while negotiations were ongoing.

The lack of expertise has led to some strange situations. Foreign lawyers have almost all had to work with just two Icelandic law firms – one of which was previously a specialist in international human rights law rather than commercial disputes. But even those currently litigating acknowledge the efforts made by the Icelandic judiciary to organise the unprecedented case load.

“Three major banks going down at once would challenge the best legal system in the world. It is a lot for the country to handle, but lawyers of the creditors have been seeking to co-ordinate with the Icelandic courts to put in place case management protocols and to streamline cases so we can work with a common purpose,” says Natasha Harrison, a partner in the securities and financial institutions litigation practice at Bingham McCutchen, who is representing more than 70 bondholders in the Icelandic banks.

Galina Alabatchka, co-founder and managing director at boutique special situations debt broker Illiquidx, says the financial and asset quality information provided by the three banks is more frequent than the information for the Lehman Brothers estate, albeit less granular. The Lehman estate also has many more different issuer entities trading, each with different claim entitlements.

Complex settlement

Even so, the resolution process has thrown a spotlight on weaknesses in Icelandic insolvency infrastructure. Regulated investors with limited risk appetite or legal resources who wanted to sell their claims on the secondary market initially found the trading process difficult.

“The winding-up boards wanted to review every transfer, and there was a 21-day delay to receive any objections to the transfer, which has now been reduced to 10 days. Brokers cannot lodge simultaneous trades to buy a block and sell it on, so each leg of the trade must be lodged separately, and they are looking at a 30-day turnaround overall,” says Alyson Lockett, a partner at Simmons & Simmons who has acted for distressed debt buyers on the Icelandic banks.

There are also many uncertainties surrounding the implications of exchange rate moves. Emergency legislation converted all foreign currency claims into krona, locked at the exchange rate prevailing on April 22, 2009. This fixes the proportion of the estate to which each claimant is entitled. But as most of the assets are denominated in foreign currencies, recoveries for creditors can still fluctuate with the exchange rate moves.

“Alternating the exchange rate can create a 20% gap in the recovery value. And now, there have been proposals that every claim will get some distribution in its original currency such as euros or dollars, so there are even more scenarios,” says Ms Alabatchka.

Disputed claims

Above all, the three banks are facing a wall of contested claims. At Kaupthing, of Ikr3233bn in claims rejected by the resolution committee, claimants are contesting Ikr2479bn. Some of the claims that the bank considers most disputable are linked to the former owners of the bank, who in turn face litigation by the bank’s estate over alleged mismanagement before the crisis.

Another problem is that Icelandic law permits third parties to challenge the legitimacy of any claim. Arni Tomasson, the chairman of Glitnir’s resolution committee, says this has prompted a wave of tactical challenges from the largest creditors, trying to eliminate as many of the claims as possible to maximise their own recoveries. The committee has had to participate in more than 1000 mediation meetings.

Despite these complications, Icelandic claims have been trading. Celestino Amore, the co-founder of Illiquidx, estimates that as much as 40% of the outstanding claims on the three banks have changed hands since the defaults.

According to Louisa Watt, a partner at specialist claims trading law firm Richards Kibbe & Orbe, Kaupthing alone apparently registered 300 claim transfers up to December 2010. But secondary trading has begun to settle down, and special situations investors are starting to turn elsewhere for opportunities. “We have learnt to work with local lawyers to look at key issues such as assigning a claim, creditors’ rights, voting rights in insolvency, so we are looking at those things in Greece, Portugal, Spain and Ireland as certain investors feel they have taken enough exposure to Iceland and are looking to the next situation,” she says.

Surprise bill

Meanwhile, Mr Tomasson received an unpleasant surprise in June 2011. Having realised about Ikr300bn in cash from the bank’s assets – about a third of the realisable asset pool – he had hoped to strengthen relations with creditors by making an interim payment to them.

But the Icelandic parliament stepped in with a bill that requires creditors of all three banks to decide whether to enter a composition agreement – which will give time to run off the assets gradually – or place the bank into liquidation for a short-term sale of assets. This had the side-effect of preventing the interim payment, which also prompted some volatility in the price of Glitnir claims in the secondary market.

“This bill came as a total surprise to us, we were not consulted in any way, and we are a bit puzzled as to what was parliament’s aim,” says Mr Tomasson.

But the economy minister, Mr Arnason, defends the bill. He believes it is vital to end the uncertainty hanging over the three defaulted institutions, and their three successor banks. “What we want to do is to safeguard creditors’ interests, to make sure that they have increased say over the estates of the fallen banks, and to limit the resolution committees from operating in some sort of no-man’s land. We think it is very important to increase ownership discipline on the estates of the fallen banks, and through them in the cases of Glitnir and Kaupthing on the new banks that are owned by the estates,” says Mr Arnason.

Depositor priority

By far the most contentious dispute is over the government’s decision in the emergency legislation to prioritise foreign depositors over other foreign creditors – mainly bondholders and some uncollateralised derivatives counterparties. Mr Arnason says this was essential to preserve the Icelandic economy.

“If we had not taken the decisions inherent in the emergency legislation, our society would have resembled the Stone Age. The banking system would have crumbled, every services company or small industry would have collapsed overnight, and unemployment would have sky-rocketed. What would be the realistic chance of creditors to gain from their claims under those conditions?” he asks.

While bondholders do not dispute the importance of protecting retail depositors, they are contesting the emergency legislation and its consequences on several grounds. Defeated in the Reykjavik District Court in April 2011, bondholders are taking their case to the Icelandic Supreme Court, which will begin hearings in September 2011.

The first contention of the bondholders is that the emergency law is illegal as it retroactively sought to prioritise the international depositors who had previously ranked pari-passu with other unsecured creditors.

“A government is permitted to take appropriate steps in an emergency, and Iceland clearly needed a solution in October 2008. But the direct consequence of retroactively prioritising international depositors was to wrongfully expropriate the property of the remaining unsecured foreign creditors, without compensation, and to transfer it to another group of creditors. That is illegal both under the Icelandic constitution and the European Convention of Human Rights,” says Ms Harrison at Bingham McCutchen.

Of course, the change in the law was not retroactive for those investors who bought claims only after the default. Alongside the German sparkassen, landsbanken and co-operative banks that seem to be casualties of every financial accident, the list of claimants against Landsbanki in the Reykjavik District Court in April 2011 included special situations funds such as Arrowgrass, Third Point Partners and GLG European Distressed Fund.

The second complaint concerns the decision of foreign deposit guarantee schemes to compensate in full depositors in Landsbanki’s overseas retail arm Icesave, which was mainly active in the UK and Netherlands. The bondholders are asking for the court to enforce the Icelandic ceiling equivalent to around €20,000 ($28,430) per deposit, which would radically reduce the size of the priority c

laim. But they have so far been caught in a political pincer between the British government who chose to guarantee the full value of deposits in 2008, and the Icelandic government that agreed to repay the UK government and step into its shoes as the priority claimant on Landsbanki.

“We have not been given a seat at the table at any discussions between the UK and Icelandic governments. We have worked hard to find solutions, but no one currently wants to engage in discussions,” says Ms Harrison.

What’s in a name?

Finally, bondholders are challenging the decision to treat wholesale deposits as priority claims alongside retail savings. Wholesale depositors included other financial institutions, and local authorities in the UK and elsewhere. Many of these wholesale deposits looked more like money market investments – fixed-term (usually one-year), high-interest deals, each arranged separately through brokers.

Indeed, the Glitnir resolution committee originally ruled that they should be treated as general rather than priority claimants, but it was overruled in the district courts. In one case, when Spanish-Libyan bank Aresbank filed a claim for damages on the grounds that its money market deposit with Landsbanki should have been transferred to Landsbankinn, the claim was struck out on the grounds that the deal should be regarded as an interbank loan.

Even in the April 2011 ruling on the main Landsbanki case, the Reykjavik District Court accepted that “specific main characteristics distinguish these loans from deposits. The business did not involve the payment of a sum of funds to the bank for storage or to use payment and general banking services.” But the court still found that wholesale depositors should remain priority claimants.

Bonds wiped out

Ms Harrison says her clients will be ready to petition the European courts on the grounds of wrongful deprivation of property if the Supreme Court hearing goes entirely against them. Interestingly, while robustly defending the emergency legislation as a whole, Mr Arnason does not take a view on whether wholesale deposits should count as priority claims, but rather says this is purely a matter for the courts to decide.

This dispute does not concern Kaupthing, which already repaid retail depositors in 2009 and had few wholesale deposits. Kaupthing claims are currently trading at 24% of face value, according to prices quoted by Icelandic broker Keldan. Glitnir trades at 26%, since it has a larger estimated estate value relative to the size of claims.

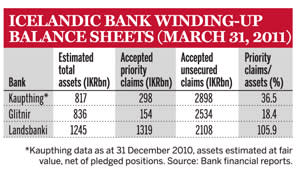

The most severely affected bank is Landsbanki, as a result of both the Icesave claim and the size of wholesale deposits. Its estate may not even be adequate to cover all the priority claims (see table), so that bondholders would be wiped out.

Despite this, Landsbanki claims still trade at 6% of face value according to Keldan. But Ms Alabatchka at Illiquidx says this price seems to represent little more than “the cost of an option for further discussions with the administrator, or some hope of favourable exchange rate moves or room for positive surprises on the expected asset recoveries”.

Good bank, bad bank

Perhaps the most profound charge against the Icelandic government, however, is that its solution has not worked from an economic viewpoint. By contrast with Latvia's Parex Bank, or the Swedish bank rescues of the 1990s, the decision to divide the banks into domestic and foreign operations meant there was no explicit separation between good and bad banks.

The domestic customers included borrowers with foreign exchange-linked loans hit by the krona sell-off, as well as nominally Icelandic companies that were in reality being used as investment vehicles for overseas leveraged buyouts and real estate speculation. As a result, the three new banks are still grappling with restructuring their own loan portfolios.

As the domestic assets were transferred to the new banks at a significant discount, they only book impairments if the recoveries underperform original expectations at the time of transfer. This means all three new banks are profitable. But those impairments are rising, especially at Arion and Landsbankinn, where impairment charges more than doubled in 2010.

Meanwhile, except at Arion, total customer loans are shrinking – by almost 6% at Islandsbanki in 2010, and more than 11% at Landsbankinn. This is hardly conducive to economic growth.

“The government wanted to protect the domestic economy by separating out domestic assets. But instead of creating three defaulted banks and three healthy banks, they have really just created six bad banks,” says Jon Danielsson, an Icelandic economist who lectures on financial crises at the London School of Economics.

Delicate balance

The model in Iceland at least had the advantage of transferring domestic assets to the new banks at a discount, which was imposed on the defaulted banks. In Ireland, the government imposed the discount on the 'good banks' when they transferred assets to the National Asset Management Agency, which left the surviving banks with huge capital needs. At Alvarez & Marsal, Mr Melngailis says it is a delicate balance choosing how to apportion assets between good and bad banks.

“You need to understand what the future core strategy of the good bank will be. You want to get the non-performing assets out, but you also want to make sure the good bank is left with an asset base that is large enough to support an ongoing business,” says Mr Melngailis.

Mr Arnason acknowledges that returning the three new banks to full health is “the key challenge we are confronted with. We are in a stage of transformation where the three new banks have to move from being asset management companies to being fully operable banks.” He says the government is striving to encourage that change, partly by increasing regulatory penalties for non-performing loans to incentivise banks to restructure their portfolios as quickly as possible.