Will Portugal be the next domino to fall? Amid fears that the Greek debt crisis could spread across southern Europe, this was the unsettling question that international financial markets forced the Portuguese government to address earlier this year.

After pushing a late budget and a four-year austerity programme through parliament, Portugal's minority Socialist Party government appears to have satisfied investors, credit rating agencies and the European Commission that any such misgivings were unfounded.

"There may have been some doubt in the markets at the beginning of the year, but I think it has now been clearly established that Greece is an isolated case and needs to be treated that way," says Nuno Teixeira, vice-president of Portugal's Banif Invest Bank.

The threat of contamination by the Greek crisis may have been averted, but Portugal still faces several difficult years of deficit reduction and slow growth. The Bank of Portugal forecasts gross domestic product (GDP) growth of 0.4% this year after a contraction of 2.7% in 2009. While the government sees annual growth climbing to 1.7% by 2013, a number of international economists fear even that modest projection could be over-optimistic.

Growth will be restrained by a pressing need to cut the budget deficit, which soared from 2.7% of GDP in 2008 to a record 9.4% last year as the government pumped money into the economy in a relatively successful effort to mitigate the impact of the global recession. Reducing this deficit by almost two-thirds in four years without choking an incipient recovery is the biggest challenge.

"The country is in a serious situation, but I don't see any dramas ahead," says Fernando Ulrich, chief executive of Banco BPI, one of the Portugal's top five banks. "We performed better than most other European economies last year. The increase in the deficit was an unpleasant surprise, but there are other EU countries with bigger deficits of 10% and 12% of GDP. The most important point is that credible measures to reduce the deficit are now in place."

Deficits to the rescue

José Sócrates, Portugal's centre-left prime minister, is fond of quoting Paul Krugman, the Nobel prize-winning US economist, to the effect that: "deficits saved the world". If governments did not run up deficits during a recession, says Mr Sócrates, they would not be doing their job. Increased public spending, he says, helped Portugal emerge from the global downturn ahead of most other countries, with a slight upturn in the second quarter of last year.

But it was the unexpected increase in the deficit, which soared by almost seven percentage points of GDP in a single year, that raised concerns. Douglas Renwick, an associate director with Fitch Ratings, says it was this "sizeable fiscal shock", combined with economic and structural weaknesses, that caused Fitch to cut Portugal's long-term government debt rating in March, lowering it by one notch from AA to AA- with a negative outlook.

The downgrade placed Portugal at the same level as Ireland, Italy and Cyprus in terms of its sovereign debt rating, two notches above Greece, which has a Fitch rating of BBB+. Standard & Poor's had lowered the outlook on its A+ rating for Portugal to negative in December. Moody's also has a negative outlook on its AA2 rating for Portugal.

Fitch's decision focused the minds of Portugal's political parties as they voted the following day on the government's stability and growth programme, which aims to reduce the deficit to 2.8% of GDP in 2013, a cut of about €9bn, from €14bn in 2009 to about €5bn.

Garnering support

Fernando Teixeira dos Santos, Portugal's finance minister, called on opposition parties to send an "unequivocal signal" to international financial markets that the plan had cross-party support. In the event, the programme was endorsed by a narrow margin with the reluctant support, in the national interest, of the main centre-right opposition party, which abstained. All other opposition parties voted against the programme.

The need for the minority government to win opposition support for legislation and the possibility of it being brought down by a censure motion were among several factors that had raised doubts over Portugal's capacity to discipline its public finances.

After four years in office, Mr Sócrates was re-elected to a second term in September. But the Socialist Party lost their overall majority in parliament. Rather than seek to form a coalition, he opted to form a single-party minority government that can be brought down by a combined vote of opposition parties.

Although Mr Sócrates defends increased public spending as a defence against recession, last year's sharp rise in the deficit was seen partly as a consequence of an election year in which the Socialists were keen to postpone inevitable cuts in public spending. The election also delayed approval of the 2010 government budget until February and the stability and growth programme until March.

When it was finally unveiled, the austerity programme met with general approval on a technical level. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development welcomed it as a strategy for "maintaining market confidence, supporting growth and ensuring fiscal sustainability". There were similar plaudits from the International Monetary Fund and the European Commission.

"The plan has been given the benefit of the doubt," says Mr Ulrich. "Some felt it could be more frontloaded with tougher measures in the early years. But if it had not been credible, the markets would have penalised Portugal and we would be paying higher spreads for funding than we are. The markets will now want to see how well the government implements its own plan. I am hopeful that by the end of the year we will be paying much lower spreads."

A four-year public sector wage freeze, cutting military investment by 40% and delaying a high-speed train project for two years are among measures included in the austerity plan, which aims at reducing public investment from 4.9% of GDP last year to 2.9% in 2013. Social spending is to be reduced by 0.4% of GDP over four years. Public debt is forecast to peak in 2012 at 90.1% of GDP, up from an expected 85.4% this year.

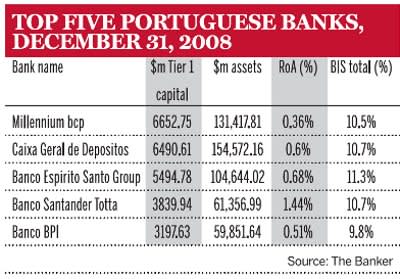

Top five Portuguese banks, December 31, 2008

Banking prospects

The performance of Portuguese banks in 2010 and beyond will be highly dependent on how successfully Portugal implements this plan, which aims to simultaneously cut the deficit and nurture a modest economic recovery. In a report published in April, Fitch Ratings said that bank profitability would also be affected "by any adverse reaction in the capital markets reflecting concerns over the government's fiscal position. This would increase their wholesale funding costs and make access to markets more difficult."

While the five leading Portuguese banks saw a general decline in profitability and asset quality in 2009, they proved more resilient than many of their international peers. Banco Espírito Santo, Santander Totta and Banco BPI all achieved higher net income than in 2008, although they benefited from large capital gains from financial operations and assets sales.

The impact of lower interest rates on net interest revenue saw net income drop by almost 40% at state-owned Caixa Geral de Depósitos (CGD), the country's largest bank by deposits. This reflects the fact that CGD's loan book has a larger proportion of mortgage lending, where spreads cannot easily be increased. Net income remained flat at Millennium BCP, largely due to lower revenue from its international operations. Increasing the spreads on about one-third of its corporate loan book proved insufficient to compensate for the increasing cost of customer funds in its Polish operation, says Fitch.

Lending capacity

Unlike many other European banks, Portuguese groups, with the exception of Santander Totta, continued to expand their lending in 2009, although at lower levels than in the past. "Credit growth has decelerated considerably in recent years," says Mr Ulrich. "Lending is currently growing at rates of zero to 5% a year at most Portuguese banks, compared with annual rates of 10% to 15% before the crisis". This has helped redress a considerable imbalance between fast lending growth and a relatively slow increase in deposits, which are currently growing at about the same rate as credit.

Fitch says that continued lending growth in 2010, particularly from the banks' international operations, should benefit net income revenue. This, together with a continued widening of lending spreads, will "help to maintain or even improve margins". However, the report adds that competition for deposits is likely to remain strong and wholesale funding costs relatively high in 2010, adding to pressure on interest margins.

International spread

Portuguese banks have been steadily increasing their international operations, particularly in the fast-growing Portuguese-speaking countries such as Brazil, Angola and Mozambique, to compensate for slow economic growth in their domestic market. Sluggish growth and low productivity have long been seen as Portugal's greatest vulnerabilities and a decade of growing below the EU average has damaged the competitiveness of a small economy that can no longer rely on currency devaluations to boost exports, as it regularly did before joining the euro.

But slow growth has at least spared Portugal some of the problems that the global recession has inflicted upon the EU partners it once hoped to emulate. "Growth in Spain and Ireland was driven by property booms that ultimately proved to have been artificial," says Mr Teixeira of Banif. "While Ireland has had to create a 'bad bank' and the level of non-performing loans in Spain is five times higher than in Portugal, the Portuguese financial system is well-capitalised, profitable and in good shape."