New infrastructure is in great demand in the UK and easy to spot.

Giant wind turbines rise out of farmland and coastal sea areas. Roads, pavements and verges are dug up for laying optical fibre cable. Tunnel-boring machines had barely finished the 21-kilometre underground stretch of the 117-kilometre, £15.4bn ($20bn) new Elizabeth Line railway before another new excavation had started on a colossal tunnel across London, the £4.2bn Thames Tideway ‘super sewer.’ In south-west England, on the banks of the River Severn estuary, 3200 people are preparing foundations for the £20bn Hinkley Point C nuclear reactor. Construction is finally about to begin on the £56bn High Speed 2 rail line from London to Birmingham, Manchester and Leeds.

This is only part of UK government's ambition for infrastructure, seen as key to boosting lamentable levels of productivity, ensuring continuity of energy supply while slashing carbon emissions, bridging the north-south economic divide, and placing the UK at the forefront of global technological change. In July, the National Infrastructure Commission, which is part of the Treasury, called for nationwide full-fibre broadband by 2033, half of UK power to come from renewables by 2030, all new vehicles to be electric by 2030, ‘resilience’ against extreme drought and flooding, and £43bn to be invested in "stable long-term transport funding for regional cities".

Where's the money?

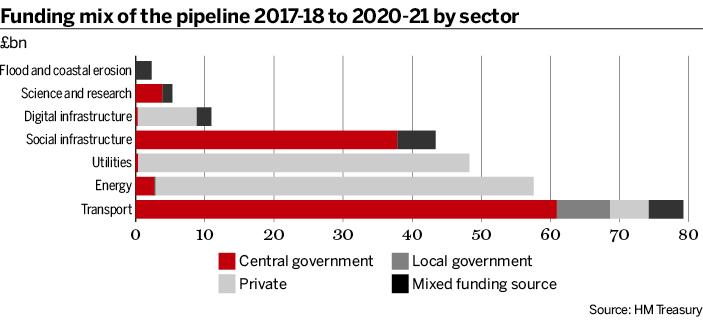

These laudable goals inevitably beg the question of how it is all to be paid for. The government wants the private sector to finance about half of the projected requirement of £60bn each year in infrastructure investment, but there is no assurance that investors will be willing to meet its goal.

There is no lack of cash. “The money is there. The project pipeline for offshore wind is a good example. Year by year, there are extremely large funding requirements in offshore wind, and it’s being gobbled up by the market,” says Christopher Quayle, a director at HSBC’s infrastructure and real estate group.

Mike Weston, chief executive of investment manager Pensions Infrastructure Platform, agrees that “significant amounts of finance” are available from pensions. Infrastructure remains “an attractive asset class in terms of its long-term cash-generative characteristics, and it fits certainly with where defined benefit schemes are in their journey. They need cash-generating assets as they get more mature and take some risk out of the scheme.”

Under EU rules, there are benefits too in terms of calculating capital adequacy from holding investment-grade infrastructure debt. “Insurance companies have made big moves into infrastructure debt in recent years because of its attraction on a Solvency II basis,” says Mr Weston.

PFI problems

The problem is that the lion’s share of this capital is going to existing projects that are inherently less risky and more appealing to investors. “For brownfield or existing operational assets, there is a huge appetite and international interest, with a big, liquid secondary market,” says Stuart Lea, HSBC’s global head of infrastructure and real estate.

There is a dearth of greenfield projects tailored to investor needs in the market. “What is potentially constraining delivery of some of these assets is how they are funded and how they are paid for,” says Mr Quayle. “Whatever the means used by the private sector to finance a project, it needs repaying, and that means taxpayers, or a similar sort of body, ultimately needs to bear the cost of the assets. It is the procurement model and the avenues through which these assets are paid for in the long term that really needs addressing.”

One particular issue is how new social infrastructure is to be funded now that chancellor of the exchequer Philip Hammond has formally closed the door on the Private Finance Initiative (PFI). Before the financial crisis of 2008, the PFI had been prolific, but in recent years it has become politically toxic.

“I remain committed to the use of public-private partnerships [PPPs] where they deliver value for the taxpayer and genuinely transfer risk to the private sector. But there is compelling evidence that the PFI does neither,” Mr Hammond stated in his October 2018 budget speech. “We will honour existing contracts. But the days of the public sector being a pushover, must end… I have never signed off a PFI contract as chancellor and I can confirm today that I never will… The government will abolish the use of PFI and Private Finance 2 for future projects.”

A gap to fill

The passing of PFI is clearly regretted within the industry and has given rise to much head scratching as to what might replace it.

“PFI made it easy for people to invest and for the public sector to procure those projects, because the form of the contract and allocation of risk was set and over time only needed tweaking,” says Pierre Kahn, head of energy and infrastructure for Europe, the Middle East and Africa at Deutsche Bank. “It worked very well for many years. It was a long process, quite expensive for bidders, and for big projects it clearly favoured larger bidders able to swallow those costs, but it was a framework that people got to know and which was adopted by other countries.”

According to Mr Weston, the “vast majority” of 716 operational projects using the PFI or PPPs are “running very well and delivering what they intended to deliver. As is always the case, the good get victimised with the bad.”

The portfolio of HICL, a UK-based equity investor in infrastructure, bulges with schools, hospitals, prisons, police and fire stations built according to the PFI formula, although Harry Seekings, co-head of infrastructure at InfraRed Capital Partners which manages HICL investments, is keen to stress that “less than one-quarter [by value] of the acquisitions that HICL has made over the past three financial years have been UK PFIs”. He also wonders what will follow. “The government has not yet defined how it wishes to involve private capital in funding the UK’s future infrastructure investment needs. HICL looks forward to entering into dialogue with the Treasury,” he says.

One possible route forward would be to emulate the non-profit distributing (NPD) variant of PFI/PPPs introduced by the devolved government in Scotland, where it has been used to build roads, colleges and hospitals. In the NPD capital structure, equity carries no dividend entitlement and there is a fixed percentage return on loans to the project. Any surplus profits are paid to the Scottish government.

Certainty and stability

Mark Braithwaite, senior managing director at Macquarie Infrastructure and Real Assets, points out that the reason why regulated UK utilities such as water, gas and electricity have proved so attractive to private capital is the “clear and transparent framework to invest in, whether you are an equity investor or a lender. They give steady, predictable cash flows over the long term, which you can marry with long-term equity and long-term debt. One of the underpinnings can be that you obtain a long-term investment-grade credit rating. If you have got all those mechanics in place, with a strong investment-grade credit rating, you can more easily fund projects.”

The benefits of certainty and stability of revenues are evident in the surge of wind generation projects that employ ‘contracts for difference’ with the government for the electricity they produce. The UK already has 1625 operational wind projects with 9112 onshore and offshore turbines, according to Renewable UK, an industry body. “The government doesn’t underwrite that – it just pays according to the amount of power that is delivered to the grid,” says Mr Lea of HSBC.

Opinion is more divided on equity and debt investment in providing ‘full-fibre’ optic cable with the aid of government incentives. Goldman Sachs is one of the latest to bankroll UK broadband through a £2.5bn investment. The plan is to lease the fibre lines to companies such as Sky and Vodafone, while also selling fibre to mobile phone companies to connect masts.

“The digital revolution only works if you have widespread ultrafast broadband, and the UK sits pretty near the bottom of full-fibre penetration across the world,” says Ed Clarke, co-founder of Infracapital, the infrastructure equity investment arm of M&G Prudential’. Infracapital owns Gigaclear, which is rolling out fibre in rural parts of the UK.

Mr Weston is less enthusiastic. Unlike renewable energy, there is no security of revenue, and most of these business plans rely on establishing local fibre monopolies. “Once you’re there, you basically wholesale that cable to all the Skys and Virgins of this world.” This could change dramatically should “we all decide to go wireless,” he points out.

Pension catch-up

For several years, the Treasury has been encouraging UK pension schemes to step up investment in infrastructure, but even after pooling some of their funds, Mr Weston concedes their asset allocation to infrastructure is still only about 2%, a fraction of their Australian and Canadian counterparts. This mainly reflects structural and historical differences. The rate of pension contributions in Australia and Canada is much higher, and their pension schemes are a great deal larger. For instance, as of June, the Canada Pension Plan Fund totalled C$366.6bn ($277.7bn). Australian and Canadian capital markets are dominated by natural resources and have smaller populations than the UK, so there is also more incentive to diversify into real assets.

Persuading institutional investors to help fund large and expensive greenfield projects is no easy task, but many in the industry say the Thames Tideway project ticks all the boxes. “Our view is that it is a fantastic project,” says Mr Weston. “It’s long term and has attractive cash flows that are very secure and inflation-linked. The great thing about the Thames Tideway model is that shareholders start generating returns on their investment from day one, and they don’t have to wait until construction finishes. That’s really important, because long construction projects with no yield cannot attract pension schemes.”

Mr Braithwaite of Macquarie is another fan. “Normally a project such as that would have to get done on the government balance sheet because of the risks – a seven-metre-diameter tunnel under the River Thames and Houses of Parliament is as risky as it gets. What Thames Tideway did was modify the regulated utility model and wrap it around the project. The same regulatory framework was put in place, so that investors coming in could understand what future revenues were going to be. This received a strong credit rating, which enabled debt and equity to be raised at a low cost of capital,” he says.

Government exposure is limited to insuring against catastrophic risk, for which Thames Tideway pays a fee. Costs are recovered through higher bills for Thames Water customers. Critics say it would have been better, with 10-year Treasury rates under 2%, to have funded the project through government borrowing. Bazalgette Tunnel, the builders of Thames Tideway, counter that their cost of capital during construction is an astonishingly low 2.5%.

Mr Weston believes that opinion is split inside the Treasury on the merits of Thames Tideway. It is possible that a similar funding structure could be used for a new EDF nuclear reactor at Sizewell in Suffolk, he adds.

Going nuclear

The type of nuclear reactor that EDF is building at Hinkley Point has been plagued by technical problems and cost overruns. EDF and its Chinese partner hope to recoup their investment through a high ‘strike price’, guaranteed by government, for the electricity to be generated. This too has led to much criticism, but Mr Lea of HSBC is more sympathetic. “It’s just not physically possible for a contractor to take all of that risk and provide the government with value for money,” he says.

A new generation of ‘small modular reactors’ being developed and tested may alter investor aversion to nuclear power. The new reactors are intended to be standardised and ‘factory built’, and at a much lower cost.

“Depending on the financing and funding, they could be perceived as quite a sensible long-term pension investment,” says Mr Weston. “If government funds their construction, they could be sold off as soon as operational. Then you would have pension schemes keen to invest in an operational asset, and the government could take the capital and use it to fund the next one.”

What if more public money could be sourced? Lord Jitesh Gadhia, a veteran of investment banking who now sits on the board of UK Financial Investments, proposes using £100bn of the £435bn in gilts that the Bank of England has acquired through quantitative easing to fund UK infrastructure. His idea is not as outlandish as it may sound to many at first. The government’s own National Infrastructure Assessment calls for a state ‘infrastructure finance institution’ to be established if the UK loses access to funding from the European Investment Bank following the UK’s exit from the EU.

“In the absence of PFI, what the government is saying is either we use things such as contracts for difference, as with the energy sector, which is what’s being used for nuclear at the moment; or a regulatory asset base, where we can guarantee a return; or the government’s guarantee scheme, which would help guarantee debt. That can all help you raise the debt funding, but where is the equity going to come from?” asks Lord Gadhia.

“Someone is going to have to take the risk on development, which goes through multiple cycles, from proof of concept to final investment decision, and then getting it up and running. Plus, there will be various development risks you take on, particularly if it is using technology that is yet to be totally proven. If public intervention is necessary to address market failure, it should be targeted on areas of the risk spectrum which the market is unable to fund.”