The news of effective Covid-19 vaccines has raised hope that the world could soon return to some semblance of normal life. However, the economic impact of the pandemic will continue to be felt strongly throughout 2021 and the global banking sector faces numerous challenges.

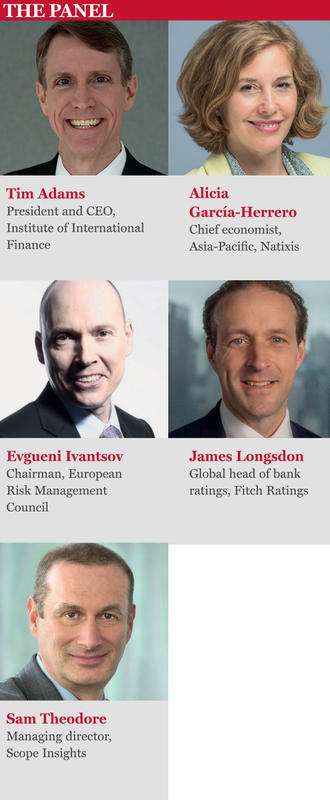

The Banker has polled a select panel of industry experts to discuss the outlook for the banking industry in 2021. Participants discuss how banks can manage an inevitable increase in loan losses, the measures they can prioritise to best support the economies in which they operate, the lasting effects the pandemic may have on banking business models, and where opportunities could arise.

Q: What is the single biggest challenge facing banks in 2021?

Tim Adams: The Covid-19 pandemic is still the single biggest challenge and many economies could remain in a holding pattern for much of the year until a reliable vaccine is distributed. Policy support must continue until we’ve effectively defeated this virus. I urge ongoing action — action that is coordinated and appropriately consistent across jurisdictions. It’s imperative that we avoid creating fragmentation, which is a top threat to the effectiveness and agility of the [global] financial system. All of that being said, I am an optimist by nature and see numerous opportunities on the horizon, instead of only challenges.

Alicia García-Herrero: Although a cyclical rebound in economic growth is likely to happen in 2021, the biggest challenge remains in the increasingly low interest rate environment for banks, which could pressure profitability. As more central banks enter the club of quantitative easing, the massive liquidity injection has helped banks to expand loans to corporates at a lower funding cost. However, the net interest margin is still likely to be compressed and the extension of loans may also mean lower net income in the short run. Even though the concern of Covid-19 may ease with the rollout of vaccines, corporates are likely to remain cautious in investment, which could hurt loan demand for capital expenditure.

Sam Theodore: The biggest challenge, put more in evidence by the pandemic, remains the sector’s stubbornly high excess capacity. The main struggle is not so much the adoption of digital routes, as virtually all banks are moving down this track and some doing it better than others. It’s about shedding excessive legacy infrastructures (physical branches and back offices) that are both costly and increasingly redundant. Especially since, with lockdowns and social distancing, more bank customers have been moving online — many for the first time. But large banks cannot easily fold their legacy infrastructure and start anew as a digital alter ego. With the difficult realities of pandemic-stricken economies and the need to preserve an acceptable public image, they need to balance their priorities. But the pressure is there and will not relent, especially in France, Spain, Italy, Germany, Benelux, Austria and the UK.

Evgueni Ivantsov: From a risk manager’s perspective, it would be difficult to name one single biggest challenge because we are now in the midst of the deepest crisis in living memory. Covid-19 has amplified most of the risks that banks normally deal with. I would say that mitigation of the growing credit risk for main asset classes will be the biggest challenge from a financial risk perspective. If we look at non-financial risks, the biggest challenge will likely to be ensuring robust operational resilience from both a technological (especially in cyber security) and human capital perspective. In addition, climate change risk will remain the main challenge not only in 2021, but for many years to come.

James Longsdon: The biggest challenge for banks will be managing the economic fallout from the Covid-19 pandemic. Governments will start to wean the private sector off various forbearance, moratorium- and furlough-style schemes as we emerge from the depths of the health crisis. Sovereign balance sheets have significantly shielded the private sector from the acute economic shock in 2020, but we expect impaired loans to rise in 2021 and for low interest rates to pressurise returns. The extent of the challenge facing banks is uneven, with a swifter economic recovery expected in parts of Asia-Pacific, notably China.

Q: How can banks manage surging non-performing loan (NPL) volumes while maintaining resilience and treating customers fairly? Will timely NPL resolution prove more challenging than in previous banking crises?

Mr Ivantsov: The current situation is a ‘perfect storm’ for banks. With their resources already stretched, banks urgently need to leverage technology to address these pressure points. A survey of UK-based chief risk officers, recently conducted by the European Risk Management Council, has confirmed this statement: 64% of respondents plan to expand digital capabilities in 2021 to mitigate the impact of the Covid-19 crisis.

Timely NPL resolution is much more challenging during the Covid-19 crisis than previous crises. Governments provide substantial financial support to businesses and people, which helps them to sustain the initial pandemic-induced shock. However, it also creates a latent delinquency. For banks, it has become difficult to identify problem customers early and start a timely resolution. It also creates a cliff effect. When government support is finally removed, banks might suddenly face a ‘tsunami’ of previously undetected NPLs, which can make the situation even more difficult.

Mr Theodore: While NPLs should rise next year, they will likely not worsen to anywhere near the levels reached during the last crisis. This time around, central banks and governments across Europe were quick in supporting businesses and households to survive the pandemic crisis on an unprecedented scale. There is no plausible scenario within the EU, or even in the UK, for a sudden drop in this support, as long as the pandemic crisis will not have subsided — hopefully in a few months’ time as vaccination broadens. Rather, support should see a gradual downward adjustment, most probably in line with economic recovery rates. This, alongside supervisory leeway in recognising and provisioning for NPLs, and urging the use of capital buffers if needed, should keep the banks fully engaged in maintaining lending to the real economy.

Mr Longsdon: There will definitely be a balance to be struck — there always is when it comes to dealing with stressed borrowers. But this time, treating customers fairly is of even greater relevance because the health crisis has put the issue of social inequality at the centre of political and media discourse in many countries. Pre-existing labour market inequalities have been accentuated and investors are placing increasing weight on environmental, social and governance (ESG) considerations in their investment decisions. All else being equal, and without some sort of state-sponsored ‘bad bank’ buyer of NPLs, it will take longer to resolve NPLs than was the case in previous banking crises.

Sovereign balance sheets have significantly shielded the private sector from the acute economic shock in 2020, but we expect impaired loans to rise in 2021

Mr Adams: The global financial system is significantly safer, stronger and more resilient than ever. Banks hold over $3.7tn in more capital, more liquidity and less leverage than at any point in modern history — meaning that we are able to put our balance sheets to work to fuel the global recovery, and that’s just what we’ve done.

There is no question that what we’ve seen is a real-time global stress test, the likes of which have never seen before. However, the system performed well, and authorities appropriately reinforced the system with hundreds of policy actions and accommodations.

Ms García-Herrero: In many economies, the steep fall in growth has surpassed previous shocks. The good news is that central banks have acted quicker and have become more accommodating in providing liquidity. With the build-up of the regulatory framework in the past years, banks have been given more leeway in temporarily relaxing some requirements, including capital buffers. This usually comes in exchange for a higher tolerance for NPLs. Therefore, banks should adopt a fair approach in extending loans to corporates suffering from the short-term shock and differentiate those from prolonged zombie firms. Due to the quick and massive injection of liquidity, banks may find it easier to restructure and write off NPLs, as well as selling to other investors through asset securitisation under a low-yield environment.

Q: What measures should banks prioritise to help bring economies back onto a path of growth?

Mr Theodore: In the new landscape, going all-out to maximise shareholder value should no longer be a top goal for banks. Not if banks want to earn the image of a helping hand rather than be stuck again with that of an unreformed spoiler. A change of profile is needed and banks now need to cater to a broader range of stakeholders than just return-on-equity-hungry shareholders.

The absolute priority needs to be helping their business and individual clients survive the pandemic and recover at the end of it. Nothing else [should matter], even with the risk of being painted as excessively risk-averse by some investors. This means banks could wisely decide to steer away from re-engaging in high-risk, high-return transactions and other such activities, especially beyond their home markets.

Ms García-Herrero: Banks are at the core of economic activities and the key is really to share the responsibilities of the short-term shock and ensure corporates can navigate through the crisis by providing liquidity. First, banks could extend loans or delay repayment if a firm is facing severe pressure. Second, banks can restructure loans with longer time frames, but lower monthly repayments if necessary. Third, banks can relax collateral requirements in some cases, which will be even more powerful coupled with a government guarantee programme. However, the key is to differentiate between firms facing cyclical pressure and structural problems, and provide enough liquidity for them to get through the crisis.

Mr Longsdon: Banks entered the pandemic with sound balance sheets. This gives them the opportunity to be part of the solution to the crisis rather than an accelerator. I think banks will want to prioritise maintaining credit supply to solvent borrowers and supporting the capital market needs of their corporate and public-sector clients. The supervisory backdrop has been supportive, adopting a flexible stance on the use of capital buffers. Banks have been reluctant to expand balance sheets to that extent, but they have not needed to because capital markets have been strong. As defaults rise, the temptation will be to tighten underwriting standards. Banks will have to tread a fine line between over-tightening and appropriate prudence.

Mr Adams: Thanks to the swift global response and the strength of the industry, our latest research indicates global growth will contract by only 4.2% in 2020 — more than during the global financial crisis, but much less than was feared a few months ago — and grow by 5.3% in 2021.

However, this is not the time to pull back support. It is crucial that policymakers continue to provide fiscal support and accommodative policy, especially for households and small and medium-sized businesses that have been most impacted by the virus.

Mr Ivantsov: Each major economic crisis opens a new chapter of economic development where some business areas become obsolete and new businesses emerge, which will create the foundation of the next economic era. Banks should play an active role in identifying these new business areas, as well as the social trends that will drive the future economy. Investing in and funding these areas should be the priority. Banks also need to ensure they remain financially solid, well capitalised and liquid, as a healthy and well-functioning banking system is one of the necessary preconditions for economic recovery.

Q: What will be the pandemic’s lasting effects on banking business models?

Ms García-Herrero: The lasting effects of the pandemic on business models may be larger on retail banks compared to institutional banks. The Covid-19 outbreak has changed consumer behaviour in embracing digitalisation and remote services. Traditional retail banks may face challenges in providing services and products not only from their branches, but through other means. This is indeed an ongoing trend, but the pandemic is clearly going to accelerate these changes.

These developments are favourable for virtual banks without branches in reducing hurdles to attract customers. More competition between traditional and virtual banks is expected to be seen and different players will emerge in the upcoming decade.

The Covid-19 outbreak has changed consumer behaviour in embracing digitalisation and remote services

Mr Theodore: In the post-crisis years, there has been a marked adjustment in most large European banks’ business models, in the direction of stronger balance sheets, lower risks and back-to-basics strategies. It is no exaggeration to note that, on aggregate, Europe’s large banks appear to be in their best prudential and financial shape in several decades. There has also been a gradual but unmistakeable narrowing of the ranges of business models and strategies across the sector, with no notable outliers in sight.

It is very likely that, in the post-pandemic years, business models will remain risk-averse and anchored in financing home markets’ economic growth. This is more important in Europe, which remains a highly bank-intermediated credit market, than in the US, which is much less so.

Mr Longsdon: We have identified several ‘megatrends’ arising from the pandemic that will affect business models and bank ratings over the longer term. The most important for business models are even-lower-for-longer rates; growth in online economic activities, or activities without human intervention that accelerate structural digital transformation; and invigorated efforts to shift to a more sustainable and equitable economy. Business models will likely shift towards more fee-based products; more sophisticated client interfaces, where partnerships with non-banks and big tech become more commonplace; and take increasing account of social inclusion and consumer protection developments. Loan books will need to adapt to increasing financial and regulatory incentives to favour sustainable or ‘green’ assets over ‘non-green’ or ‘brown’ assets.

Mr Adams: The most immediate and lasting impact is going to be the prioritisation and use of digital tools for consumers and employees alike. Many questioned whether work could truly be done digitally, but in most instances, it’s been a success — a credit to the heavy investment in technology and IT resources over the last few years. Going forward, the cost and operational benefits of remote working, like less need for physical locations and a much nimbler mindset to responds to future crises, means that this trend is here to stay and technology spends will likely increase.

Mr Ivantsov: The Covid-19 crisis works as a booster of the trends that began to emerge before the crisis. It appears the future will belong to cashless, fully digital, agile, flexible and customer-driven banking services. Banks that can better adapt to these global trends will be the winners; and those who are slow in recognising and reshaping their business models to these trends will likely lose their market shares and possibly disappear.

Q: Where do you see opportunities for banks in 2021?

Mr Ivantsov: The Covid-19 crisis has clearly revealed the mainstream banking trends of the future; banks shouldn’t miss the opportunity for a deep and comprehensive digital transformation in 2021. The time for experimenting in ‘digital sandboxes’ is over. Incumbent banks should re-invent themselves as truly digital and agile organisations. From a risk-management perspective, the crisis has created an opportunity and strong incentive for all banks to build a robust tail risk management framework, which will be vital for successfully sustaining future extreme shocks.

Financing growth for fintechs has slowed considerably during the pandemic and bank customers seem less keen to migrate to them

Mr Theodore: A major risk for banks in recent years has been digital disruption, especially the threat coming from fintechs and big tech. The pandemic has been reshuffling the deck, so far to the banks’ advantage. First, their public image has been improving, as they are being counted on to support the economy, rather than being blamed as reckless troublemakers.

Second, for fintechs, financing growth has slowed considerably during the pandemic and bank customers seem less keen to migrate to them, especially in Europe. Also, the fact that fintechs remain less regulated than banks is not helping confidence, especially after the Wirecard debacle.

Third, big techs’ more negative image problem may make them more hesitant to compete head-on with incumbent banks, unless they are invited by the banks (as has been the case with Apple, Google and Amazon). This does not mean that digital disruption is less of a threat for banks, but they now stand a better chance of going where they need to be in the digital space without being disrupted on the way.

Mr Longsdon: The opportunities will fall mostly to bigger banks and to well-capitalised banks that can afford to invest at a time when their management is still engaged in managing the economic fallout from the pandemic. We have already seen some merger and acquisition (M&A) activity in the US, Spain and Italy in 2020. Domestic deals are likely to continue in 2021 in over-banked sectors where smaller banks are struggling with profitability pressures associated with the low rate environment, above-trend loan impairment charges and a need to invest in digital capabilities. Big bank cross-border M&A probably represents a risk too far at this stage, but bolt-on cross-border growth opportunities also exist for bigger banks.

Ms García-Herrero: Under a low-yield environment, banks will continue to see demand from yield-hunting investors. Other than traditional bonds and equities, investors will seek returns from safe and alternative investments, which could mean asset securitisation from different types of underlying to provide stable income streams, which could be properties, data centres or green energy projects. This is not only important for insurance companies under the structural trend of an ageing society, but for governments to utilise domestic saving to boost economic growth under the mega trend of de-globalisation or re-globalisation.

Mr Adams: Sustainability and ESG issues have emerged as some of the most important issues affecting the financial system and global economy. Sustainable projects and sustainable financing need to be the name of the game — consumers want it, investors want it and society is demanding it. Moreover, the policies of the next US administration could likely trigger a rapid acceleration of global momentum on climate change. With strong political commitment and an active partnership with the financial sector, this shift will help bridge the gap between economic and environmental goals and bolster inclusive growth.