Many Western banks are rebounding from the huge losses of 2008 and have strengthened their grasp on the top of the rankings, but elsewhere the pain is just beginning. Philip Alexander reports.

The storm has passed, but the clear-up goes on - and the weather looks set to be unsettled for some time. The process of global bank deleveraging has manifested itself all too clearly in The Banker's Top 1000 World Bank figures with the total assets of the Top 1000 falling by almost $1000bn to $95,532bn. But this is perhaps part of a healthy cleansing process.

ORDER YOUR COPY NOW

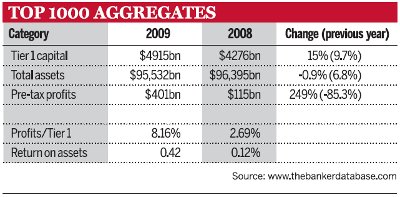

Profitability has rebounded significantly in this year's rankings, almost quadrupling to an aggregate of more than $400bn, based on end-of-2009 results, compared with only $115bn in last year's rankings.Return on capital has not increased at the same rate, however, reaching just 8.2% this year from 2.69% in last year's rankings, and still well below the 20% recorded in 2007. This slower rise reflects the continued process of recapitalisation, taking the aggregate Tier 1 for the rankings to $4915bn, up 15% on last year. While that may dilute return on capital, it is also a reassuring sign of strengthening, in the Western financial sector in particular.

The aggregate capital-to-assets ratio (CAR) for the Top 1000 reached 5.1% this year, up from 4.4% last year. The recapitalisation among the top 25 banks in the rankings is even more striking. The average ratio calculated using Bank for International Settlements (BIS) definitions - which includes all forms of capital and adjusts assets by risk-weighting - stood at 12.87% for the top 25 last year. Now it has risen to 15.47%, as leading banks respond to a more volatile world economy and the pressure from regulators to hold a larger (and higher-quality) capital cushion. In addition to banks raising more capital, the BIS ratio increase is also the result of reducing assets - down about $800bn for the top 25.

Go west

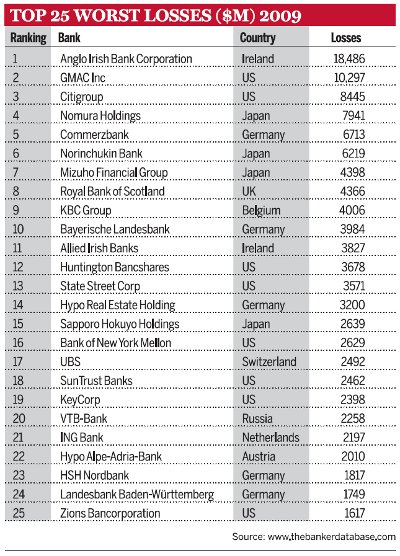

And who are these revived and recapitalised banks? As it turns out, the death of the Western banking sector has been greatly exaggerated. Several of the leading victims of the subprime crisis continue to haemorrhage money, but other banks in the US and western Europe have rebounded with vast increases in profits: Wells Fargo up an extraordinary $65.4bn, with Credit Suisse and Deutsche Bank both returning to profit in dramatic style. Two banks that have broken into the top 10, Barclays and BNP Paribas, are also among the biggest gainers in terms of profits. Even those that are still losing money, such as Citigroup, Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS) and UBS, have pared back losses significantly.

In fact, the top 25, which recorded an unprecedented $32.4bn loss in last year's rankings, have returned to make a positive contribution of $19.1bn this year. This is not the product of major changes in the composition of the banks in the top 25: two US banks switch places at the top of the rankings, and many others have hardly moved.

There are two new entrants to the top 25, both the products of post-crisis mega-mergers. Lloyds Banking Group absorbs HBOS to enter straight in at 12 (Lloyds itself was at 48 pre-merger, with HBOS at 32). And the French banks Groupe Banques Populaires and Groupe Caisse d'Epargne, at 35 and 63, respectively, in last year's rankings, have merged to form Group BPCE, which comes in at 18.

While Lloyds has managed to withstand the problems in the HBOS loan book and record a profit of $1.7bn, Groupe BPCE is taking longer to recover from the crisis. The losses of the two banks combined last year were $4.2bn, mostly from Caisse d'Epargne, and this has narrowed to $530m in the 2010 rankings.

Squeezed out

The two banks squeezed out of the top 25 are Agricultural Bank of China, which held Tier 1 steady and slipped from 24 to 28, and Japan's Mizuho, which suffered a 12.5% fall in capital and dropped 10 places to 26. The Japanese bank's performance is more representative. Agricultural Bank aside, Chinese banks in general were some of the year's top gainers, and Industrial Commercial Bank of China (ICBC) for the first time dislodged a Japanese bank (Mitsubishi) as the highest-ranked Asian bank. By contrast, Japan's sun continues to dip, and Japanese banks are especially prominent among the largest losses and largest declines in profit. Last year, Japanese banks in the Top 1000 recorded pre-tax profits of $16.5bn. This has collapsed to a loss of $11.1bn in the latest rankings, just as Western banks have recovered.

ORDER YOUR COPY NOW

The market factor

But beware: the improvement in profits among Western banks may have much to do with the sharp recovery in global stock markets and other market-based assets during the second half of 2009.

For the first time, The Banker has this year expanded the data points that we capture to include about 30 new variables. Not all of these are shown in the Top 1000 here in the magazine, but all are available online at www.thebankerdatabase.com. One of these enhancements was to request banks to submit the risk-weighted assets measurements that they use to calculate their BIS ratios.

This allows us to see which banks have a high proportion of market-risk-weighted assets in their portfolio. It is no surprise that Goldman Sachs, the investment bank that obtained a universal banking licence in 2008 to access Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) coverage, is near the top of the list. But other banks with high market-risk ratios include RBS, Standard Chartered, Deutsche Bank, Belgium's KBC Group and both the Swiss banking giants, Credit Suisse and UBS. Of course, we cannot know for sure how sensitive these assets are to market movements, but the fact that the risk-weighted list includes several of the banks that enjoyed the biggest improvement in profitability in 2009 suggests that the stock market declines of 2010 will cause some pain. What is also striking is the number of Russian banks, often closely held by a small group of private owners, that are high up the list.

Russian exposure

Russian banks proved especially exposed when the country's stock market plummeted in late 2008 and early 2009, either directly or through clients using shares as loan collateral.

Russia's state-owned Gazprombank rebounded from a $2.6bn loss in last year's rankings to a $2.6bn profit, and the bank acknowledged stock market exposure as a significant factor in its annual reports. Closely held National Reserve Bank, which has a higher proportion of market-risk assets than Goldman Sachs, was among the global top 25 banks for return on assets in this year's rankings. But, again, it remains to be seen whether these performances can continue in weaker stock market conditions.

Plain vanilla banking

With regulatory pressure on US and EU banks to separate or curb proprietary trading operations, enforced by potential capital charges for poor risk management, all but the top trading houses are likely to devote more of their resources to plain vanilla deposit banking.

The era of smaller banks trying to enhance return on assets with small-scale trading activities for which they cannot manage the risks may well be over, at least for as long as institutional memory lasts.

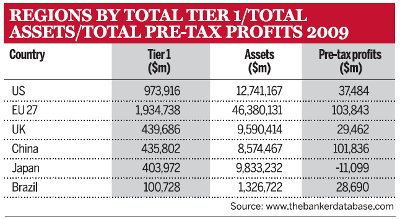

So what does the world of banking look like without relying on a rallying stock market? Emerging market banks tend to have a more traditional business model based on retail and corporate lending rather than financial market exposure. Profits at these banks have continued to grow, with China up almost 20% at $102bn, Asia (excluding Japan) rising 10% to $160bn, Brazil more than doubling to $28.7bn and Latin America as a whole also doubling to $35bn.

But these improvements pale in comparison with the rebounds enjoyed in the US, UK and EU, where losses of $91bn, $51bn and $16bn, respectively, in 2009 turned into profits of $37.5bn, $29.5bn and $103.8bn in the 2010 rankings. As a result, the contribution of profits from emerging markets to this year's total has dropped substantially. China alone accounted for 73% of global banking profits in the 2009 rankings, compared with only 25% this time around.

ORDER YOUR COPY NOW

The lesson that profits based on trading operations can be more spectacular but more volatile than traditional bank lending is hardly new, although the past few years have brutally reinforced it. What will be newer is the economic environment that banks face, as the debt-driven boom of the past decade gives way to slower growth this decade.

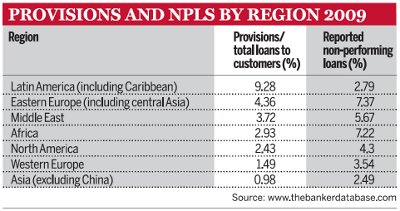

Provision and impairment

Another enhancement to our rankings is the incorporation of provision and impairment data, together with a greatly improved fill rate for the non-performing loans (NPL) data field, for which information was provided by 80% of banks in this year's survey. What these data suggest is that many banks may not be fully prepared for rising NPL rates as their clients struggle with slower economic growth. Latin America and the Caribbean stands out as a notable exception. Although only about a quarter of the region's banks reported NPL data, far more gave their provisioning numbers. As against reported NPLs averaging 2.79%, the region has already provisioned 9.3% of its loan book, implying that it is well prepared for economic downturn.

A profitability drag

Contrast this with Asia (excluding China, where banks did not provide provisioning data). Reported Asian NPLs are already at 2.5%, but provisioning is less than 1%. Or Africa, where provisioning of 2.9% is dwarfed by NPLs of 7.2%. Banks in these regions may have demanded high collateralisation on loans, perhaps valuing the collateral conservatively, or they may be hoping that a bounce in collateral values and economic recovery will enable improvements in the loan book quality before actual loan losses are crystallised. Either way, if economic growth does not impress, further provisioning is likely to drag on the profitability of banks.

The reported NPLs of individual banks also shed light on the countries in which they operate. Privately owned Banco Macro in Argentina has reported NPLs of 3.3%. By contrast, Argentinian state-owned banks have either submitted no NPL data or have taken on far lower provisions (less than 1% in the case of Banco de la Nacion).

In Spain, the mutual banks known as cajas have provisioned for 0.7% of total loans, with the notable exception of Caja de Ahorros y Monte de Piedad de Cordoba - better known as CajaSur. This bank took provisions of 3.5%, which was enough to trigger losses of $777m in 2009, reducing the bank's Tier 1 capital by almost 70%.

CajaSur had to be rescued by the Spanish government in May 2010, but could be the canary in the caja coalmine. In June 2010, ratings agency Standard & Poor's (S&P) revised its loan loss assumptions on Spanish banks up to 5.3%, together with an eye-watering 14.5% for real estate-related lending - a speciality of the cajas. This shows just how far many of these banks may have to go in making provisions, and they have very little cash and low profitability with which to do it.

Excluding CajaSur, total loans for the cajas in the Top 1000 are $1656bn, versus total profits of $6.8bn and Tier 1 capital of $116bn. The S&P assumption of 5.3% loan losses would equate to almost $88bn among the cajas in the Top 1000, and more government bail-outs cannot be excluded.

The China story

On paper at least, Chinese banks are in a far healthier position. Of the 115 new entrants to this year's rankings, 37 are from China. Five of these are the result of better data transparency, as their figures have become available for the first time. But the other 32 have expanded their way into the rankings in the past year, with the highest new entrants being a number of rural credit unions that have merged into fully fledged commercial banks.

Of the 84 Chinese banks now in the rankings, the average NPL ratio is just 1.54%, and 65 of the banks are reporting NPLs of less than 2%. However, as The Banker flagged up in its June 2010 edition, many observers are sceptical that such low NPL ratios truly reflect the health of the banking sector. Fitch Ratings analyst Charlene Chu notes the growth of unreported lending such as discounted merchant bills and bank-to-bank loan transactions. She is also concerned that bullet repayment credits and the rolling over of delinquent loans disguise whether or not clients will ever have the means to repay.

Reduced share of NPLs

But, above all, the speed of asset growth in China has inevitably reduced the share of NPLs in the total portfolio. In the Top 1000, reported Chinese bank assets are up by almost 27% this year in aggregate. The average CAR and BIS ratios for the Chinese banks may provide a better measure of safety than NPL data alone, as they show the cushion available if those bad loan figures prove to be optimistic.

The CAR and BIS ratios for Chinese banks were steady in this year's rankings, at 6.5% and 13.1%, respectively. But they are noticeably lower than those of other leading emerging markets where banks face similar risks, such as opaque client balance sheets and the expansion of lending among untested customers.

The equivalent CAR and BIS ratios for Brazil are 10.6% and 14.3%, and for Russia 16.1% and 23.3%. Only in India are banks less well capitalised relative to their asset base and, even there, the BIS ratio is fractionally higher than for China, suggesting that Indian banks have a higher proportion of low-risk assets.

State lender of last resort

In practice, even if some Chinese banks find themselves in need of a capital injection, they need look no further than the $2400bn foreign exchange reserves of the Chinese government. In last year's Top 1000, we noted the role of taxpayers' money in maintaining the capitalisation of troubled Western banks. Straight government equity injections in the US and western Europe largely came to a halt in 2009, and indeed a number of prominent rescued banks such as UBS and Bank of America repaid their home governments.

But as the financial crisis of 2008 transformed into an economic slowdown in 2009 - with global gross domestic product growth of just 1.3%, according to the International Monetary Fund - state support for banking sectors migrated from advanced into emerging markets. With the exception of Russia and Kazakhstan, this did not generally take the form of government rescues of ailing banks. Instead, state-owned banks have assumed an increasingly important role as lenders to the real economy, picking up the slack where the privately owned banking sector is in retreat.

The Russian government has continued to ramp up the Tier 1 capital of 100% state-owned Russian Agricultural Bank and Gazprombank (the latter partly to replace losses incurred in 2008), while participating in the September 2009 share offering of VTB on a pro rata basis to maintain its 85% shareholding.

In Ukraine, where high levels of foreign ownership limit the government's capacity to influence private banking activity, two formerly small specialist state development banks, Oschadbank and Ukreximbank, have been massively capitalised to allow greater lending to the real economy.

Oschadbank hurtles straight into our rankings for the first time at 335, the largest Ukrainian bank, while Ukreximbank is up 349 places, to 455, after a 187% capital increase. In Brazil, the Tier 1 capital of state-owned urban development bank Caixa Economica Federal is up 65%, and that of the 90% federally owned Banco do Nordeste more than doubled.

The argument of governments supporting state-owned banks in this way is that such banks do not undercut or poach business from the private sector - they are making loans that private banks are not prepared to consider. But it will be interesting to see what will happen to the capital and assets of these state-owned banks once the crisis begins to fade and private banks become more active again.

Focus on capital quality

The enhancements in the depth and breadth of data collected for the Top 1000 rankings coincide with the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision's work to redraft the Basel II agreements on bank capital in light of the lessons of the financial crisis - now generally known as Basel III. The consultation document published in December 2009 had drawn responses from more than 270 individuals and institutions worldwide, including many of the world's largest banks, by the time consultation closed in April 2010.

ORDER YOUR COPY NOW

The final outcome of the Basel Committee's deliberations is therefore uncertain, but several clear themes emerge. One is the desire to return to purer definitions of capital - excluding items such as deferred tax assets from Tier 1 and placing less reliance on Tier 2 as 'loss-bearing' capital. The second theme is tougher stress-testing of loss assumptions as part of the process of measuring risk-weighted assets: already, in June 2010, the Basel Committee has announced adjustments to the framework for measuring market risk.

Affected regions

Using two indicators from the Top 1000 rankings, The Banker can create an impressionist guide to which regions and countries might be most affected by the tighter environment for regulating bank capital. First, looking at the banks that are closest to the upper limit of Tier 2 (which must not exceed Tier 1) in their capital structure shows which may be required to raise the proportion of Tier 1. Second, by observing the largest divergences between the Top 1000's total assets and the total risk-weighted assets calculated for BIS purposes, it is possible to gauge where banks will be most sensitive to tougher assessments of asset risk weighting.

Latin America and the Middle East look least affected, with risk-weighted assets equivalent to more than 70% of total assets in both regions, and Tier 2 at 19% of Tier 1 capital in the Middle East and just 7.5% in Latin America.

In eastern Europe (including central Asia), there has been heavier reliance on Tier 2, which is almost 27% of Tier 1 on average. But this is offset by a stringent approach to risk weighting, with the result that the risk-weighted assets for the region are equivalent to more than 80% of total assets.

Overall, western Europe looks the most affected region, and certain countries stand out. Italian and Austrian banks have been relying heavily on Tier 2, at 43% and 40% of Tier 1 capital on average (and much higher in individual cases). Meanwhile, Swiss banks have managed to secure particularly low risk weightings: risk-weighted assets are just 36% of total assets on average. This suggests that Swiss banks might find themselves with an increased value of risk-weighted assets (and hence a lower BIS solvency ratio) if regulators were to demand tougher stress tests of the risks on their books.

Liquidity requirements

There is a final element to the Basel reforms that has many banks expressing concern: liquidity requirements look set to be tightened significantly.

The Top 1000 already collects data on loan-to-deposit ratios and liquid assets held as a proportion of deposits. While fill rates for both these data fields have roughly doubled this year thanks to a more intensive collection process, they are still less than 70% (less than 50% for the data on cash held), which makes meaningful analysis more difficult.

However, we hope to continue making improvements in data collection that will allow still deeper insight from the Top 1000 next year and beyond. The Banker and its research team greatly appreciate the effort put in by participants in this survey, and their understanding that providing as much data as possible makes the resulting rankings even more valuable to all our readers.

The research for The Banker's Top 1000 rankings was carried out by Adrian Buchanan, Guillaume Hingel, Charles Piggott, Valeriya Yakutovich, Adrian Knight and Ramona Tzanaki.

Watch the videoTop 1000 World Banks – 2010 |