The US and European national stock exchanges are now firmly in the acceptance stage of psychiatrist Kübler-Ross’s five phases of grief. After a period of complacency, cries of double standards and attempts to bargain with regulators, they are now coming to terms with the increasingly competitive landscape in which they operate. And they have finally taken meaningful action.

As their home market shares eroded, the incumbent bourses looked to drive down costs by buying cheaper technology and slashing staff numbers, but even the most ruthless could only cut so far. After that, the most obvious route to increased efficiency is to capitalise on economies of scale by playing to one of the exchange groups' key strengths – sheer size – and becoming even larger. Enter the recent contagious outbreak of M&A activity amongst some of the world's biggest exchange names.

A continuing trend

Of course, those involved in the intercontinental manoeuvrings do not always agree – at least publicly – that the recent frenzy of announcements and speculation on tie-ups between bourses across the globe is caused by competition. Some, including David Lester, director of information services at London Stock Exchange Group and chairman of the firm’s multilateral trading facility (MTF) Turquoise, suggest that this could just be seen as the continuation of a long trend towards larger and larger exchange groups – the logical next step from the last round of major tie-ups in the mid-2000s.

Whatever the claimed motivation, the reality is that relying solely on revenues generated through cash equities is no longer a tenable position for a trading platform, and those that have traditionally done so have found themselves in something of a disagreeable position of late.

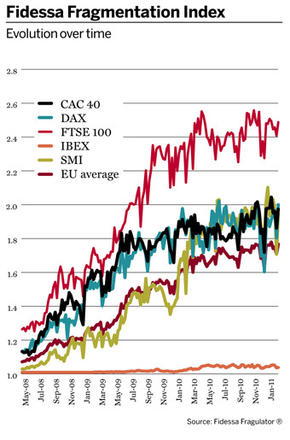

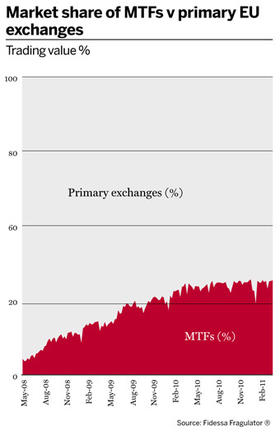

In the US and Europe, exchanges have found themselves menaced by the alternative trading platforms loosed by Regulation National Market System (Reg NMS) and Markets in Financial Instruments Directive (MiFID), respectively. This may not be news to market participants, but the results have been acutely traumatic for the incumbents nonetheless. Exchanges elsewhere may soon feel the squeeze too. Australia is set to allow stock exchange competition from late 2011, and Canada’s Toronto Stock Exchange has already seen its market share eroded by newly launched rivals.

Nimble upstarts

The upstart platforms based their businesses around offering faster trading at prices that made the existing exchange heads’ eyes water. They are also far nimbler, with staff numbers and overheads a fraction of the traditional operators. Chi-X Europe, for example, which has just 50 employees, netted 15.54% of European lit equities trading volume in February 2011 (compared with London Stock Exchange’s 13.77% and Deutsche Börse’s 12.12%), according to Fidessa data (European trading in dark pools accounts for less than 5% of European stock trading). By contrast, the London Stock Exchange (LSE) still has more than 1500 staff, despite recent cuts. The comparison is perhaps an unfair one, because the LSE has a far larger franchise, but the difference remains significant.

These differences would not be so troublesome if the LSE’s trading volumes were growing; minor, and even rather less minor, inefficiencies tend go unnoticed in the midst of a rapidly growing market.

Unfortunately for the LSE, its monthly value traded on the UK main market and AIM companies in March 2011 was just under £119.39bn ($194.21bn) compared with £386.72bn four years previously, before the introduction of MiFID.

US pressure

On the other side of the Atlantic, the top US exchanges are also feeling the strain. BATS Exchange, launched five years ago, now has 13.87% of US lit equities trading in February 2011, according to Fidessa, not far behind the New York Stock Exchange’s (NYSE’s) 18.54%.

A declining share of the market might be less of a problem if equities volumes were growing and the pie to be sliced was getting bigger. Unfortunately, however, once it has been dished out, there simply is not enough to keep all the trading platforms well fed.

Much to the delight of high-volume traders, the new platforms forced fees down significantly. In Europe, where it was assumed that MiFID would lead to explosive growth in equities volumes, some MTFs even ran pricing promotions that essentially paid traders to use their platforms.

Despite gaining market share, the alternative platforms suffered too. Thanks to the financial crisis and a still cumbersome clearing and settlement process, the expected uptick never happened. As a result, of all the European MTFs, only Chi-X has managed to turn a profit, and even it has joined the consolidation bandwagon after a takeover bid by a smaller competitor, BATS Europe.

Slim pickings

LSE’s Mr Lester estimates that even if Turquoise had a 100% share of all European lit equities trading, its revenue would be €50m to €60m. Divvied up between 28 national exchanges and three major MTFs, that makes for relatively slim pickings. He blames, in part, the aggressive pricing structures introduced by the new market entrants. “Equities – particularly in Europe – are suffering,” he says. “Fees are set, in my view, at an extremely and perhaps unsustainably low level.” Prior to Mr Lester’s stewardship, Turquoise too happily engaged in tough pricing promotions in an attempt to gain market share.

Chi-X’s CEO Alasdair Haynes, who will depart the firm after the completion of the BATS Europe merger, says he had long expected the competitive pressures in the European market to force the larger bourses to look for new partners.

“The arrival of MTFs was a realisation to exchanges that they had to use economies of scale to come back and compete. We’ve expected for a long time that the number of players sitting in cash equities has got to reduce and we expect people to become more global and regional in their approach going forward,” he says.

The situation in the US, where equities volumes remain several times higher than in Europe, is not quite so desperate. It may be telling then that in the two major merger bids still in play (LSE Group/TMX Group and Deutsche Börse/NYSE Euronext) the European partner will hold a dominant position.

Mr Haynes describes the LSE Group's bid for Canadian TMX Group as a “very defensive” deal, under which the two firms are being forced to consolidate in order to benefit from various cost synergies. “I think this is a deal they had to do,” he says. “Otherwise both remain vulnerable.”

LSE's Mr Lester maintains that the tie-up had a strategic motive, however. “We have strong futures as we are, but we will be stronger together, and create something greater than the sum of our parts.”

Kevan Cowan, TMX Group’s head of equities, backs Mr Lester's position. “Unlike some of the others on the international stage, this is not really a cost synergies deal,” he says. “Ours is much more revenue synergies-driven and an opportunity to expand what we’re already doing.”

Expansion was also at the heart of the Deutsche Börse and NYSE Euronext proposed merger. In particular, it also plays into new market segments – namely, derivatives. Many an exchange forced to subsist purely on cash equities will have enviously eyed bourses focused on derivatives, which continue to offer more generous pricing margins than equities.

“What I think we’re seeing is the incumbent exchanges giving up on cash equities because the low-cost providers have taken their lunch away,” says Paul O'Donnell, BATS Europe’s chief operating officer. “Now they want to move somewhere else where they’ll have a little bit of pricing power.”

Driving to derivatives

Derivatives certainly seem like a good place to start. Nasdaq OMX, which suffered along with its peers from the rise of alternative trading platforms, recently reported that its fourth-quarter 2010 US derivatives trading revenues eclipsed its US equities revenues for the first time ever. Net revenues were $42m in the three months to December 1, 2010 – up 35% year on year.

The derivatives market then, looks set to be the next exchanges battleground. The planned Deutsche Börse/NYSE Euronext amalgamation would own five options exchanges (International Securities Exchange, Eurex, NYSE Amex, NYSE Arca and NYSE Liffe) and two large futures exchanges (NYSE’s Liffe and Deutsche Börse’s Eurex operations). The result would be a derivatives giant with a truly intimidating market share, which would greatly benefit from Deutsche Börse’s clearing operations. Both exchange groups declined to comment when contacted by The Banker (as did derivatives competitor CME group), but NYSE Euronext chief executive Duncan Niederauer has already signalled his intentions to move the exchange group towards new asset classes.

The strength of such a model is obvious, says Miranda Mizen, principal and head of European research with research and strategic advisory firm Tabb Group. “If you have the derivatives and the underlying equity, you’ll get some of the synergies within the exchange. If you add in the clearing piece of that, then you have a multi-asset exchange with a vertical clearing element built in. I think there will be natural gravitation towards that as a model,” she says.

While NYSE Liffe and Eurex do not currently compete directly with each other, the removal of even the potential for competition has caused some apprehension. Market participants and industry bodies, including the Association for Financial Markets in Europe (AFME), have expressed concern about damage to competition in the derivatives space, as well as the potential increase in risk caused by dealing with fewer venues.

“If the global derivatives industry ends up with the CME Group on one side and the Deutsche Börse/NYSE Euronext operation on the other, customers aren’t going to like it,” says Mr O’Donnell. "And if they aren’t happy, that can be powerful."

Changing landscape

Of course, the genesis of the alternative equity trading platforms was an environment with a cosy duopoly in the US and an essentially monopolistic environment in Europe. In the derivatives space too, heightened competition could go some way to alleviating antitrust issues.

In Europe at least, trading platforms are already stepping up derivatives operations. LSE’s Turquoise Derivatives venture is set for launch in May, and the bourse is no doubt hoping to take advantage of the potentially lucrative revenues, and shift its focus away from a long-standing concentration on cash equities trading.

Chi-X too has announced a partnership with Russell Investments to launch a new series of pan-European indices – something Mr Haynes describes as a “fundamental start” to a move into derivatives as an asset class. “It will become the next competitive landscape,” he says. “Our strategy is about launching these indices with Russell, then introducing exchange-traded funds futures and options based on them. We want to compete in this space. And we’ll look to change the status quo.”

An obvious move?

For some, this shift is an obvious move for high-tech trading systems, which are often essentially security agnostic. Jack Vensel, global head of wholesale services at Citi, says that in his days at Island – the electronic communications network acquired by Instinet in 2002 – the long-standing joke was that if there were International Securities Identification Numbers on bottles of wine, they could quite easily be traded on the platform.

“It’s just a number you’re trading, and share size and price. The reason the alternative trading platforms started in equities is not because they saw that as an endgame, but just as a way to get started," he says. "Everyone knew how equities traded electronically, and customers and regulators knew what that looked like."

Now that the technology infrastructure is in place, derivatives could prove lucrative. “I have to imagine that if Chi-X or any of the other new ventures can start capturing some of the derivatives market, it will to a large extent go straight to the bottom line as profitability,” adds Mr Vensel.

The timing would be prescient even if equities revenues were not being squeezed, Mr Vensel says, highlighting a general appetite for more efficient futures and options trading. At the same time, regulators are attempting to bring over-the-counter trades on to exchanges in the quest for greater transparency.

Derivative difficulties

However, switching asset classes is not always easy. Derivatives markets differ in some quite fundamental ways from cash equities. At a basic level, prospective trading platforms might fall foul of intellectual copyright rules on the derivatives contracts themselves.

Many are based on indices and other proprietary, trademarked products, which are specific to the company that creates and lists them, and cannot necessarily be used without permission. Creating a new futures index product based on a major equity index, for example, could be unworkable without the index holder’s approval. This is a non-issue in equities, where no market participant can hold a copyright on an asset.

To make matters worse, a lack of netting at the clearing level will make it practically impossible – or at least very difficult and expensive – to trade futures on multiple platforms, comments Rob Boardman, managing director of equity trading services group ITG Europe.

His concerns stem from the fact that if a trader buying a FTSE 100 future on NYSE Liffe, for example, then wanted to trade it on a new platform, they would likely want to net that trade off with a sell elsewhere. That could be tough without regulatory change. “It would be very hard to do, even if the trader could get an agreement on precisely what the contract specification was," says Mr Boardman.

There may currently be more barriers to entry than in the equities world then, but they are not necessarily insurmountable, and Tabb Group’s Ms Mizen expects that these obstacles will eventually share the same fate as the pre-MiFID concentration rules, which once guaranteed the effective monopolies enjoyed by European national exchanges. “There are issues around the clearing angle and issues around intellectual property, but those to me are hurdles that will be overcome either because the regulators say so, or because competition will be fierce,” she says.

Regulatory bodies may well cast a disapproving eye in the direction of newly formed derivatives groups, should they succeed in insulating themselves and their products from competitive pressures. And in some respects and regions at least, market forces may soon be at work too, thanks to the machinations of Chi-X, LSE and others.

No matter that the exchanges' defensive measures may be attacked in the future however, they certainly exist still. And while they do, derivatives will continue to be an attractive asset class for equities trading venues struggling to survive on the meagre takings left in their once-profitable home markets.