When Christos Megalou became CEO of Piraeus Bank in 2017, he knew he would be taking on the biggest challenge of his more than 30-year banking career.

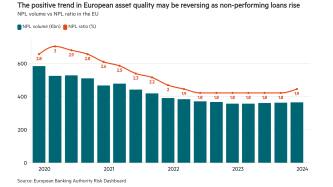

At the time, non-performing loans (NPLs) accounted for 54% of the bank’s loan book. It was familiar territory for the former investment banker who spearheaded the restructuring and recapitalisation of Piraeus’s competitor Eurobank in 2013 following the Greek sovereign debt crisis.

“That was a big challenge,” says Mr Megalou, referring to his recapitalisation of Eurobank worth around €3bn. “But it went well. So after Eurobank I left Greece and returned in 2017, when I was offered to head up Piraeus Bank, which had NPLs somewhere in the region of €35bn. That’s a big number. And it’s only through a lot of hard team work over the past six years [that] we’ve reduced this number to €2.5bn. It’s now about 6% of our [loan] book, and by the end of the year we hope to get it down to about 4%.”

Understanding the magnitude of the problem

But even for a seasoned banker like Mr Megalou, restructuring Piraeus Bank has resulted in a few sleepless nights. “The biggest challenge was to convince the regulators and the market that our strategy was going to bear fruit. And that, of course, required me to put a lot of personal credibility on the line, which has worked,” he says.

In between revealing aspects of his strategy for reviving the fortunes of Greece’s largest lender, Mr Megalou eagerly checks his mobile phone every few minutes during our meeting at The Banker’s London offices in July, to see, among other things, how Piraeus’s share price is doing.

“Our share price keeps on going up,” he says at one stage. “Our capitalisation is now around €4bn, from €1.1bn a year ago. But deep inside I’m an investment banker [he held senior positions at Credit Suisse Investment Banking for more than 20 years in London], and I know whatever goes up, goes down as well. I try to do everything I can so that it will stay up there.”

So how did Piraeus Bank go from problem child to star pupil? Mr Megalou attributes the bank’s turnaround to a combination of factors. “We started by understanding the magnitude of the problem and how to manage it. As part of this exercise we did the first sale of NPLs in Greece using real estate as collateral. We called it Project Amoeba because it was the first time a Greek bank sold secured NPLs.”

“We sold these loans in October 2018 to Bain Capital, and it was daring enough to buy the NPLs at 30 cents on the euro. A lot of people thought that was a good price because before that UniCredit had done a much bigger transaction, which got around 12 to 15 cents on the euro.

We proved to the market there were investors out there willing to buy non-performing exposures out of Greece

“Ours was a much smaller transaction – €1.5bn out of €35bn – but we still managed to get 30 cents on the euro, which was important as we proved to the market there were investors out there willing to buy non-performing exposures out of Greece using real estate as collateral.”

After that landmark sale to Bain Capital, Mr Megalou says the bank saw growing interest from firms looking to manage what was, at the time, Greece’s biggest portfolio of NPLs. “We had interest from Cerberus and Intrum from Sweden. We ended up going with Intrum, which is the biggest servicer of NPLs in Europe. It bought our non-performing exposures management unit, which we carved out from the bank with 1200 people attached to it. We sold that to Intrum for €440m of equity. It’s now managing it through an entity called Intrum Hellas where we are a 20% shareholder and Intrum owns 80%.”

The €400m it raised from the sale of the NPLs management unit to Intrum gave Piraeus the opportunity to claim another first for the bank and Greece: a €400m subordinated bond sale in 2019. “At that point in time, the bank could not raise equity,” says Mr Megalou. “That was very clear for us. In February 2020, we did a second tier-two bond for €500m with a rate of 5.5%. That gave us the opportunity to start cleaning up the bank.”

Then, Piraeus Bank went on to do an equity raise worth €1.4bn in 2021. Before that, it had exited six countries in southern Europe and the Balkans. The exit plan was part of a restructuring plan agreed with the European Commission’s Competition Authorities and included the sale of Piraeus’ subsidiaries in Serbia, Romania, Albania and Bulgaria. “As part of the restructuring plan, we agreed to eliminate foreign competition because, before I joined, the bank received state aid and one of the conditions of that aid was that we were obliged to get out of competing with European banks in other jurisdictions,” explains Mr Megalou.

The year 2022 saw Piraeus Bank return to profitability. In this year’s Top 1000 World Banks, Piraeus Financial Holdings actually topped the table of the biggest movers from loss to profit. “In 2023, we’re running at something north of 12% return of tangible book value” says Mr Megalou. “All this is anchored on a very efficient and effective retail network and a solid deposit-gathering machine. Right now, we have about €58bn of deposits, which is one of the highest numbers ever for the bank.”

Strategy for future growth

So, with the bank back on a more even and profitable footing, what is the strategy for future growth? “One big pillar is the energy transition, where we plan to invest €5bn in green projects in the next three years” says Mr Megalou. “The other big part of our growth is wealth and asset management.”

Traditionally, the penetration of wealth and asset management products among Greek households is one of the lowest in Europe, at around 12% of gross domestic product. But Mr Megalou says wealth and asset management is a growth area for both households and corporates, and now that the Greek economy is performing much better – economic activity is expected to grow by 2.4% this year – Mr Megalou says the bank’s message to customers is that they do not only need to have deposits in the bank. “In order to make better use of their money, they also need to start investing,” he says.

The bank is now in a “Goldilocks” period because net interest income is growing as interest rates rise. “We’ve also done a lot of work in network and employee rationalisation, and as part of our productivity boost, we did a lot on digital. We have quite a lot of digital offerings.”

The problem with challenger banks is that once they are up and running, valuations shoot through the roof.

Piraeus Bank can now carry out know-your-customer checks electronically, says Mr Megalou, and customers can open accounts electronically without having to visit a branch. Its “winbank” web and mobile banking app is used by more than 3 billion of its 5.5 billion customers. But it still maintains the biggest network of branches in Greece – 400 branches, which it is looking to reduce to 370 – because it serves a large number of agribusiness customers in rural areas.

A new branch model is also being rolled out, which will reduce the headcount in branches from 25 people to 15. “The aim is to reduce the total headcount of the bank from 8000 to 7000 and centralise back-office services,” says Mr Megalou. “That’s one part, and the other is the creation of a new, digital-only bank, directed towards the younger generation.”

Piraeus’s new digital bank, Snappi, is still awaiting a European banking licence. The digital-only bank is being built with the help of the bank’s technological partner, Natech, based in Ioannina, a provincial city in Greece, which has a very well-known technological university.

Mr Megalou said he did not see any of Europe’s existing challenger banks as attractive acquisitions, so Piraeus decided to build its own offering. “The problem with challenger banks is that once they are up and running, valuations shoot through the roof. They’re too expensive, even if they don’t have deposits or liquidity. So we took it upon ourselves to create something from scratch.”

Despite the fact that it will be a challenging venture, Mr Megalou says Piraeus is a big believer that the market is changing. “I see it from my own daughters. They both live in the UK, and I only managed to get them into a bank branch when we opened an account for them. That was five years ago, and they’ve never been to a bank ever since. They only use their phone. This is where banking is heading and my aim is to prepare the bank for the future.”