Ever-growing penalties for misdemeanours ranging from Libor rigging to money laundering are starting to undermine bank capital ratio calculations.

What’s happening?

The autumn 2014 joint committee report on risks and vulnerabilities in the EU financial system, produced by the three European supervisory agencies, flagged “rising and increasingly materialising concerns relating to operational risks” after a wave of bank fines related to misconduct. The report identified remediation for the mis-selling of financial products and penalties for manipulating financial benchmarks as two of the greatest sources of concern.

Just weeks later, the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) produced a consultation on revising standardised approaches for calculating the capital that banks must hold against operational risks. The BCBS noted that a study in 2010 had shown “that banks’ operational risk capital levels under the current Basel framework were on average already undercalibrated in 2009. Moreover, capital needs for operational risk were found to be increasing in a non-linear fashion with a bank’s size.”

Why does it matter?

The recalibration of Basel’s standardised approach for calculating operational risk-weighted assets (RWAs) is the precursor to a review of the advanced modelled approach used by about 15 of the most sophisticated banks in Europe and another eight in the US. That review is likely to focus on addressing the variability of risk weights for operational risk.

“It is a challenge to model forward-looking conduct risk, but what is clear is that the level of fines is rising compared with the past,” says Lars Overby, head of credit, market and operational risk at the European Banking Authority. “While there should not necessarily be a mechanistic approach, the higher legal losses need to be factored into capital requirements. We also want to see analysis of fine levels by jurisdiction as part of setting additional capital requirements under the [Basel] Pillar 2 [supervisory review] process if these [levels] are not adequately incorporated in existing operational risk charges.”

What do the bankers say?

The hard numbers show the scale of the challenge, which threatens to make banks’ operational RWA numbers almost meaningless. France’s BNP Paribas received a fine of $8.9bn for evading US sanctions in June 2014. Data from thebankerdatabase.com shows BNP Paribas had operational RWAs of $69.5bn at the end of 2013, with a Tier 1 capital ratio of 12.8%. This implies that the bank’s entire capital held against all unexpected operational risk losses was wiped out by the single US fine over sanctions busting.

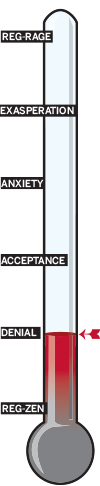

“Litigation and restitution risks have been the main surprises for banks in recent years, which have the potential to destroy 10% or 20% of capital in a few weeks,” says Rajesh Bhatia, a partner at risk and regulatory consultancy Parker Fitzgerald and a former treasurer of Standard Chartered.

The fear is that the drive for more consistent RWA calculations will make matters worse. Joseph Sabatini, who was head of operational risk at JPMorgan from 2000 to 2009, says the initial spirit of co-operation among banks and regulators to find the best approach to measuring operational risk ultimately gave way to haggling over the amounts of capital required.

“It is understandable because for regulators there is no downside to higher bank capital. But the overall effect was that the industry became too focused on quantifying operational risk rather than understanding and managing it,” he says.

What’s the alternative?

Simon Ashby of Plymouth University in the UK, the chair of the Institute of Operational Risk and a former operational risk manager in the industry, believes banks may need to make radical departures from their current methods for calculating operational risk, which reduce their reliance on statistics and scenario analysis. He suggests tapping into research on artificial intelligence.

“There are techniques being developed in complexity science, such as multi-agent approaches, that are adaptive rather than statistical. They are more likely to be appropriate for operational risk than Bayesian probability statistics,” says Mr Ashby.

As long as the models feed through into Pillar 1 of the Basel rules, however, banks may be very reluctant to invest in such experimentation in case the outputs suggest higher capital requirements. Paul Embrechts, professor of mathematics at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich, draws a parallel with catastrophe risk insurers and reinsurers. These companies face similar skewed tail risks to the legal fines now hitting the banking industry. Swiss solvency rules for catastrophe insurers do not use risk-based measures under Pillar 1. Instead, capital requirements are weighted simply according to business volumes, with the actuarial risk management aspect examined under Pillar 2.