The refinancing hurdle for European leveraged buyouts (LBOs) over the next four or five years looks daunting. Credit Suisse calculates a peak in the maturity curve in 2016, with €245bn outstanding between now and then.

Editor's choice

This refinancing must be managed during a wave of structural changes that are constraining the supply of new leveraged finance – perhaps permanently. What has long distinguished the European market from that in the US is the prevalence of banks as first choice providers of liquidity to the leveraged loan market. By contrast, in the US, capital markets have tended to provide almost all aspects of leveraged finance, except for the shorter-term or undrawn commitments that are more suited to the transactional capabilities of a bank, such as revolving credit facilities and letters of credit.

“Banks provide less term loan liquidity in the US markets because they are more focused on capital returns, so LBO sponsors have long been used to distributing in the institutional capital markets. Sometimes in the US, the bank market will not even have sufficient capacity to cover issuers who require large letters of credit, so companies have created cash-funded vehicles to make such credit lines available. That is not something we have seen in the European market because banks continue to provide letters of credit,” says Paul Simpkin, head of European leveraged finance at Citi.

Pulling back

All that is changing, however. Leveraged loans, with their low credit ratings and illiquid pricing, will face more severe regulatory capital treatment under Basel III. The eurozone crisis has raised questions about term funding for banks, which dims their appetite for long-term assets.

Those funding challenges in the eurozone show no sign of abating quickly. The largest French banks, once leading players in leveraged loans, were apparently absent from the market altogether in the final quarter of 2011, before returning in the first quarter of 2012. Even those banks that have retained high levels of liquidity are cautious. Dutch co-operative giant Rabobank retains two AAA ratings from international agencies.

“Our ownership structure, balance sheet strength and high rating are all significant advantages right now. But the realities of market conditions in the eurozone and the advent of Basel III ultimately squeeze everyone’s capacity to extend leveraged loans,” says Simon Parker, global head of acquisition finance at Rabobank.

Outside its Dutch home market, Rabobank’s acquisition finance team focuses on its food and agriculture speciality, broadly defined to include some retail and consumer goods companies such as the March 2012 £885m (€1.1bn) buyout of UK-based frozen food supermarket chain Iceland. This shows another important development. The European market has fragmented, as many banks opt to focus only on deals in their home jurisdiction, plus a few of the highest profile transactions elsewhere. Sponsors are thus deprived of the benefit of a single, large funding market of the sort that exists in the US.

Banks have also pulled back from co-investing with private equity clients. Many European banks, even among the second or third tier, kept private equity principal investment arms of their own prior to the crisis, but these are increasingly being sold to secondary buyout firms such as Lexington and Coller Capital.

Andrew Sealey, managing partner and head of financial advisory at private equity advisory firm Campbell Lutyens, says sales of private equity portfolios by banks have accounted for about 40% of all secondary transactions in recent years. These divestments have been driven by the US Volcker Rule’s pressure on principal investing and higher capital requirements on private equity holdings under Basel III.

“The strategic reason to hold these assets was to increase senior and mezzanine debt and advisory deal flow by strengthening relations with sponsors through co-investment. That rationale is diminished in a new world where many banks cannot afford to commit funds to sponsors, and any bank that is willing to lend a decent ticket size will automatically win market share,” says Mr Sealey.

Last dance of the CLOs

The other central player in the European LBO boom, pre-crisis, was the collateralised loan obligation (CLO), leveraged arbitrage investment vehicles that financed loan purchases through the sale of tranched bonds at a lower net cost of funds. What troubles sponsors is that there has been no new arbitrage CLO issuance in Europe since the financial crisis. That means the next round of refinancing up to 2016 will have to take place without them, as will any new LBOs.

Asset selection by European CLO managers generally avoided weaker credits during the crisis. But the structure had drawbacks compared with the US model. In particular, there were restrictions on trading loans below 90 pence in the pound, and a total moratorium on trading below 80 pence.

For investors who do not need high levels of liquidity and have a long-term investment profile, Europe offers greater potential for capital appreciation because the market is trading about four points lower than the US on average

“When the average price fell into the 60s [pence] at the height of the crisis, many CLOs could not manage their profile at all,” says Martin Horne, a managing director at the European arm of Babson Capital, one of the largest CLO managers and an affiliate of US life insurer MassMutual.

Even if the structure is overhauled, the illiquidity of CLO paper during the Lehman crisis has deterred many institutional investors from re-entering the market. Finally, new European rules on securitisation require originators to keep 5% of the equity tranche of each new issue. This will prevent most smaller CLO managers from originating new vehicles, as they cannot retain so much equity on their own books. Larger CLO managers such as Babson Capital Europe have already diversified their offering into more flexible unlevered credit funds.

Bond alternative

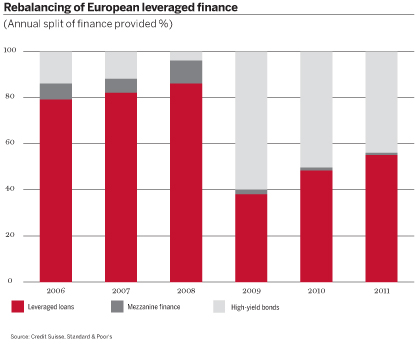

to curb dependence on banks and CLOs. They now account for as much as 44% of European leveraged finance issuance, compared with 14% in 2006.

“Loan investors are becoming more pragmatic on high-yield co-financing. Previously, they would typically have asked for seniority over bondholders, but now they are happy to see a bond issue ranking pari passu with them to help to reduce their total exposure in situations where they also want to stay invested,” says Matthew Gibbons, co-head of leveraged finance at BNP Paribas.

Jonathan Rowland, former European head of financial sponsor coverage at Citi, co-founded private equity financing advisory firm Tomorrow Partners in 2011. He highlights deals such as the €300m bond for Lion Capital’s buyout of Picard, which had been bought by financial sponsors twice before with pure loan financing.

“We are seeing deals, especially in the mid-market segment, that would previously have been funded with bank loans and mezzanine capital and would not have considered going to the high-yield market. But today, they can access the high-yield market with a similar blended cost of capital,” says Mr Rowland.

But high-yield bonds do not suit every borrower. Investors are very ratings-sensitive and liquidity can dry up quickly. French car rental company Europcar, rated CCC, offered a high-yield bond with a guidance yield of 11%, but ended up paying 14% in May 2012 to close the deal. Moreover, loans provide more flexibility for borrowers to refinance or repay before maturity if the sponsor exits earlier than expected. By contrast, issuers would tend to pay a call premium to exchange a high-yield bond.

Beyond Europe

Consequently, the search is on to find a new loan investor base in Europe. Large US banks Wells Fargo and PNC have apparently started to run the rule over European LBOs with a view to stepping up participation. Asian banks have plentiful liquidity, and there has been much talk of players from China and Australia becoming more active in the European leveraged loans market.

So far, there is little hard evidence to confirm the talk. In fact, National Australia Bank appears to be moving in the opposite direction, announcing a strategic review of its UK subsidiary Clydesdale Bank that has included pulling out of the local leveraged finance market altogether.

The one genuine increase in activity seems to be coming from Japanese banks. Nicolas Dowler, joint general manager of the leveraged finance group at SMBC Europe, says that the bank’s management is keen to develop the leveraged finance business in Europe. “The Japanese population is shrinking, so it is becoming structurally more difficult to grow profits at home. That means there is more emphasis on the rest of the Asia-Pacific region, as well as on Europe. And we have the competitive advantage of being well funded in all the major currencies,” he says.

In addition, SMBC Europe’s diversification strategy mirrors that of its key corporate clients, which ties in with the position of the European leveraged finance team. A growing number of European LBOs are being sold by sponsors to Japanese strategic buyers, including, in the past 18 months, Swiss pharmaceutical company Nycomed, UK cash-handling technology company Talaris and auto services company Kwik Fit.

SMBC Europe’s leveraged loan portfolio has expanded over the past year to $1.85bn today. But the bank is conservative in its selection of deals – nothing in the retail and fashion sectors, and very limited exposure to other cyclical sectors such as chemicals and autos.

Go West

If banks and CLOs will not carry the leveraged finance industry, then conventional asset managers have a chance to fill the gap. US funds are the logical first port of call, since they already dominate the leveraged loan market in their home country. More than 70% of European leveraged loan issuance was syndicated into the US in the first quarter of 2012. Daniel Norman, head of the US-headquartered senior loan group at ING Investment Management, says that the group has about 20 different portfolios with about $10bn in loan assets under management. Several target a European loan allocation of about 10% to 15%, while one of the group’s funds invests more than 70% of its assets in loans to European companies.

“For investors who do not need high levels of liquidity and have a long-term investment profile, Europe offers greater potential for capital appreciation because the market is trading about four points lower than the US on average,” says Mr Norman.

However, there is general consensus that larger companies with a presence in the US, or at least clear dollar-denominated revenue streams, are more likely to attract the attention of US funds. Belgian chemicals company Taminco, which raised $1.1bn in a combined bond and loan deal in January 2012 to finance an LBO by Apollo Asset Management, earns 50% of its revenues in dollars.

Leland Hart, a managing director in the leveraged finance portfolio management team at BlackRock, the world’s largest fund manager, had a decade’s experience in the European leveraged loan market before he joined BlackRock in 2009. But he is not rushing to invest in Europe at the moment, especially as deal flow and economic growth are healthier in the US.

“The downside is the lack of liquidity and transparency in the European market, making it difficult to buy in scale or trade the assets. From a fiduciary viewpoint it necessitates a careful matching of investor expectations and capital deployment,” says Mr Hart.

New providers

It would be more reliable for European borrowers to access local lenders who know them best. One key impediment to the development of a US-style loan market in Europe is that the EU Undertakings For The Collective Investment of Transferable Securities fund format does not allow investment in loan assets. In addition, the bank-dominated nature of the European loan market has led to historically lower levels of information disclosure.

“The loans market would be helped by a demonstration of the intention to improve liquidity – establishing ISIN [individual identification] numbers for loans and more public credit information disclosure. The European loan market would also be transformed by enabling the mutual funds model to be rolled out to European retail investors,” says Marc Pereira-Mendoza, a managing director in the European leveraged loans sales team at Credit Suisse.

Until the retail market opens up, new European leveraged loan funds will rely on institutional investors. Neil Thomson created and headed the internal financing team of large European global private equity firm Apax Partners up to 2010, before co-founding Tomorrow Partners with Mr Rowland in 2011. While the pull-back of banks and CLOs appears to create an obvious opportunity for new senior lending funds, Mr Thomson still sees challenges for would-be new entrants.

The downside is the lack of liquidity and transparency in the European market, making it difficult to buy in scale or trade the assets. From a fiduciary viewpoint it necessitates a careful matching of investor expectations and capital deployment

“The difficult nut to crack for flexible credit funds is attracting the right investors for an asset class that will typically yield 8% to 10%. The big credit-seeking capital providers such as pension funds would require 5% to 6% returns in an asset class that has higher liquidity. The hedge fund or private equity money is comfortable with lower liquidity, but expects 15% to 20% returns, for which you would need a leveraged structure,” he says.

He believes that large institutional investors are gradually seeing the appeal of leveraged loan investing, but further dialogue will be needed at the chief investment officer level with pension and sovereign wealth funds to generate substantially increased liquidity. That kind of access is not typically available for a start-up fund with $200m under management, so the market will tend to favour the largest established fund managers such as Blackstone GSO or KKR, at least initially.

These firms will focus on scale, however, leaving a gap for mid-market LBOs. So far, only three funds to cater for this market have been raised in the UK, with two more attempted fundraisings faltering. One of those that succeeded was launched by long-standing private equity fund of funds HarbourVest, which raised £140m through a closed-end fund, HarbourVest Senior Loans Europe (HSLE). This offers end investors access to a market that was previously the exclusive territory of the banks, including arranging fees along the life of the transactions.

“The sponsors are looking for additional sources of funding, but they still want a relationship term lender who understands their market and is accommodative. The due-diligence process can be long and intensive, so sponsors expect co-operation from lenders after they have opened their books. They fear lenders who change style to become predators, or lenders such as the CLOs that cannot be rational in certain situations because they are constrained by their fund structures,” says Karim Flitti, principal and portfolio manager for HSLE.

Change of strategy

While HSLE is built on a relationship lending model, larger loan funds will concentrate on portfolio selection like a conventional asset manager. That will fundamentally alter the position of borrowers and the pricing they can achieve.

“Investors that only have a lending relationship with the borrower would not rely on other products and services to compensate, which would indicate that you will see higher, more market-standard pricing for loans,” says Mr Norman.

Private equity firms have already reduced their traditional reliance on acquisition advisors to arrange funding as well, with most recruiting in-house financing teams, often from the investment banks. Mr Rowland says sponsors are also likely to use a broader range of financing forms, including asset-based finance, receivables or inventory financing, and sale-and-leaseback deals.

Buyouts will need more equity and lower leverage to obtain higher credit ratings. Deal flow at the moment is quiet, while sellers adjust to the lower multiples that fund managers are likely to seek to make a transaction worth their while.

“To find companies that are growing fast enough to support a tighter amortisation schedule, a higher equity commitment and still get sponsors the 20% return they are seeking is very challenging,” says Edward Eyerman, head of European leveraged finance ratings at Fitch Ratings.

Back to fundamentals

Operational efficiency will trump the balance sheet engineering that dominated pre-crisis, and turnaround expertise will be particularly valuable. Jon Moulton left larger private equity firm Alchemy Partners to found Better Capital in 2010, having become highly critical of the boom-time LBO model. Better Capital acquires mostly distressed companies using very little leverage, often to a timetable measured in days to prevent the loss of supplier credit and key customers. The firm raised a fresh £170m in December 2011.

“We could have raised more, but we have no interest to do so as there are not enough opportunities. There is excess capital in the mid-market and large LBO arena and the rate of deployment is low. There are 80 mid-market private equity firms in the UK, and 20 did no deals at all in 2011. But consolidation is slow, with managers preferring to live off existing fee flows even if they fail to raise new funds,” says Mr Moulton.

This is not to say that all buyouts must now be turnaround situations with pure equity financing. One private equity firm already running a different model is Sun Capital Partners, which provides its own bridge financing for LBOs, before finding loan or bond take-outs at a later date.

“The certainty and speed of our transaction model allows us a key competitive advantage. It lets us focus on the target’s fundamentals and growth potential as the deal-breaker, we do not have to over-negotiate the contracts, so we have a more pro-seller approach in many ways. That means we can win preferred bidder status without pitching high on price,” says Michael Kalb, head of Sun European Partners.

Of course, the probability and expected cost of the eventual financing must still be factored into that bid price. But this is where Sun Capital’s 13 years of experience comes into play. Mr Kalb says that the firm has had to widen its network of lenders, as well as arranging its own clubs for deals that would once have been taken and syndicated by a single relationship lender. But the take-out time has not increased significantly, and is still usually less than six months.

“We typically get the eventual financing done within a few basis points of our expectation. Our model is no secret, but it is not so easy for other funds to just start bridging their deals from scratch. We have the franchise and the confidence of sellers,” says Mr Kalb.