A number of leading banks are trying to break with the traditional image of banking, which they feel is holding them back. They would prefer to be viewed as tech companies rather than banks.

This is hardly surprising. At best, banking is considered old-fashioned; at worst, banks are seen as irresponsible because of their role in the financial crisis.

How much nicer, then, if banks could convince both analysts and customers that their real character is that of a tech company with a banking licence. Customers might then flock to them as they do to Apple or Facebook. Analysts and investors would give them a higher rating based on potential growth rather than mark them down in anticipation of regulatory costs and fines.

Probably the only major bank that is truly convincing in declaring itself a tech company is ING. Even though the Dutch bank was badly scarred by the financial crisis, requiring €10bn in assistance from the Dutch government, its tech roots go back to the launch of the branchless operation ING Direct in the late 1990s. The bank then had to sell ING Direct USA – as well as investment management and insurance arms – to comply with European Commission rules on state aid. The UK and Canadian Direct businesses were sold to raise funds.

ING has a presence in 40 countries including the core markets of the Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg, and ‘challenge markets’ such as Germany, Austria and Spain.

Worth it in the long run

The restructuring has not prevented ING from forging ahead with what CEO Ralph Hamers calls its “disruptive model”, in which the bank goes ahead with products that result in short-term revenue losses balanced out by the longer term goal of increased market share. Some operations are entirely online, for example in Germany where ING has built the country’s third largest retail bank from scratch in 15 years and is currently taking on 1500 new customers every day. More recently, ING has been building itself into a digital bank with the focus on mobile as the main channel.

“We started investing in digital four to five years ago when we saw the trends coming from Silicon Valley. We saw new business models coming up, we saw the customer behavioural changes as well, and the expectations of our customers more and more to do banking on the go,” says Mr Hamers. “We were [already] known for being the internet of banks as we basically built a bank around the internet rather than the internet around our bank, and through that we created a new business model.

“Over the past couple of years, we’ve been building a digital bank, moving away from the desktop to mobile, because people have less and less time to spend [on banking]. So the mobile channel has overtaken the desktop channel, at least in most of the countries in which we work.”

But this is just the beginning. The ultimate goal is for ING to have the same platform operating across every global region (just like the big tech companies), and to create a financial ecosystem that customers are interesting in engaging with on a regular basis (as with Facebook) and on which rival banks and other companies can also sell their products (similar to Amazon).

New values

ING is trying to move away from the classic value proposition of taking deposits and loaning them out as funds to one where a large primary customer base (customers whose salary or income is paid through ING) interacts with the bank and generates fee income by buying investment and insurance products. The insurance products come from a third-party provider.

In ING-speak, this is not cross-selling but 'cross-buying', because it is a consequence of the customer visiting the bank website and finding an attractive product, rather than of a sales operation mounted by the bank.

Internally, the bank has reorganised so that instead of marketing, product development and IT departments all working in silos with the delays and communications problems this typically involves, they work together in project-specific squads which figure out the quickest way to solve a problem. Compared with the zero tolerance of mistakes typical of banking culture, these squads are encouraged to take risks and learn through mistakes. This is called the agile approach.

In a wide-ranging interview in New York, where ING was celebrating 20 years as a listed company on the New York Stock Exchange, Mr Hamers explained how he hopes the bank will be perceived differently in future.

Hidden figures

“What I see is that analysts do indeed look at us as a bank,” he tells The Banker. “The way we want to portray ourselves is as a tech company with a banking licence. Even further [ahead], I think we should basically be the largest bank without a balance sheet, if you really take it far into the future.

“Every new client that we get is costing us in the first year. So, if analysts continue to basically value us on a multiples basis, my net earnings are lower, because I am growing, so I don’t get granted [credit] for my growth [in the way that a tech company does].

“Every year we grow by 1.4 million to 1.5 million new customers, and we can actually show that a new customer coming in over time generates value, even in a digital model, because we’ve turned around… from a savings model to a primary banking model. There will be cross-buying coming in, there will be new products sold to these customers as well. The value of these customers is nowhere taken into account in our valuation.”

Despite Mr Hamers’ strong argument, the reality is that ING is perceived only as one of the better players in a lacklustre eurozone banking sector, rather than as boasting the trailblazing status of a tech company.

A report by private bank Berenberg says: “For those investors who have to own a bank in the eurozone, ING has to be top of the list. Near-term returns are limited to the dividend yield of 5% plus 4% growth in total book value/share, but this is what long-term winners in the sector deliver.”

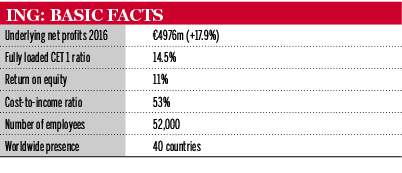

ING delivered an underlying net profit of €4.98bn in 2016, up 17.9% on 2015’s figures, adding 1.4 million retail customers, €34.8bn in net core lending growth and €28.5bn net customer deposit inflow as it did so. In The Banker’s Top 1000 World Banks 2017 ranking, ING placed 33rd, up one place from the previous results.

Tough targets

But, as with other European banks, ING’s prospects are limited by any future capital increase that may be required under the so-called Basel IV standard, and Mr Hamers says that the €1bn the bank has cut on costs will be swallowed up by additional regulatory costs. In other words, the cost of being a tech company with a banking licence as opposed to being just a tech company is considerable.

For all its vision, ING cannot escape the realities of interest rates at historic lows – ING’s net interest margin is 1.52% – with fee income only accounting for 15% of total earnings. The bank has a long way to go before it can claim to have left behind the balance sheet constraints of traditional banking and adopted a model based mainly on fee income. Return on equity is set to stay between 10% and 13%, and is currently 11%. The bank's cost-to-income ratio is 53%, and the aim is to bring it down to 50%.

“Our ambition [on return on equity], the way we set it out three or four years ago, was anywhere between 10% to 13%,” says Mr Hamers. “At that moment, we were still in restructuring from a bank assurer to a bank, and that was quite an ambitious target, but we’re hitting it. Last year it [was about] 11%. Looking forward, I think we can manage it at this level from a return perspective, even with the low interest rates, because of the cost you can attack with digitalisation.

“However, the capital levels for European banks are still uncertain because of the discussions in Basel. And that could really influence our capital levels, and that could then affect return on equity as well.”

It certainly must be dispiriting, albeit typical for a bank CEO, to see all that hard work done in cutting costs offset by new regulatory costs.

“The ambition in [cost-to-income] is to get much closer to 50%,” says Mr Hamers. “Over the past couple of years, we’ve made enormous improvements to our cost structure. We took out about €1bn of cost… but on the other side, we got a lot of regulatory costs in return: bank taxes, deposit guarantee systems, contributions to resolution funds, [all of] which is almost equal to what we took out; it’s like €850m for us last year.

“All the savings that we’ve been able to generate through our digital model were taken up by these additional costs. But we continue to invest in digital. So you can expect our costs in many other countries, from an efficiency perspective, to go down.”

New blood

ING is working on pushing revenues up by acquiring customers and launching products. “At the same time, we’re growing the number of products, we’re growing the number of clients, so the savings in efficiency on one side because of being digital will be [augmented] by investments in areas to introduce new products, [and they will give us] real growth, because we continue to grow,” says Mr Hamers. “We still get 1500 new customers a day in Germany, we still get 600 new customers a day in Spain.”

ING sets great store by attracting primary customers who will likely buy other products. The bank estimates that out of 36 million ING customers nearly 10 million are primary ones.

Mr Hamers was appointed ING's CEO in 2013 at the age of 46, becoming the youngest CEO in the bank’s history. After the traumas of the bail-outs and the restructuring, it seems the board’s thinking was that the bank needed a fresh approach. Noted for being casual in dress (at least by banking standards) and a tech enthusiast who frequently visits Silicon Valley, Mr Hamers has proven adept at getting the bank’s message across by way of short YouTube messages. He also brings an all-round knowledge of banking through his various ING postings as the local manager in Romania, the Netherlands and latterly Belgium, and as head of the commercial banking network and deputy general manager of global lending risk management. He began his career with ABN Amro, before joining ING in 1991.

While Mr Hamers has received plaudits for his techie vision for the bank, he also has an affinity for data and statistics (he studied econometrics) and uses them to make fine cost calculations. This combination of talents makes him a powerful force in contemporary banking.

Getting access

The big ambition for ING under Mr Hamers is to create a single platform across the entire bank and develop a financial hub that works more like something Facebook or Amazon would create rather than like a conventional banking portal.

“People do their banking on the go while waiting for the bus or the train,” says Mr Hamers. “They are not talking to each other, but they’re on social media. That’s where they post their blogs, that’s where they have their conversations, that’s where they put their pictures, that’s where they live their lives. The question is, as a bank, how do you get in there? How do you get into that life? Because that’s where they spend their time... and for a bank to be relevant, you have to get in there, and you have to be connected to those ecosystems, or be an ecosystem yourself.”

Mr Hamers says the goal is to create an ecosystem with a strong identifiable brand open to other types of products, including banking services from competitors.

A first step in this direction is get a single platform across the bank. “[The ecosystem can come] on the back of creating that one platform that all these tech companies have, because they have one platform across the globe, whereas banks have platforms per country.”

“I have, in the 13 countries in which [ING is] a domestic bank, 13 different apps doing exactly the same. Facebook is the same everywhere, Uber is the same everywhere, why can’t ING be the same everywhere?”

A long journey

Yet even ING, with its early adoption of technology, has legacy issues to deal with before it can create a single platform.

“It will take quite some time, for two reasons - first, even though we are a young, internet-based bank, we still have some technology that we have to renew,” says Mr Hamers. “We have many customers that we have to take along as well, so we’re not starting from scratch. We have 36 million customers who we have to take along on this journey. We have basically determined for ourselves some kind of an intermediate phase, which means that in four years’ time we want to have accomplished two things in terms of merging platforms: one big project between two branch banks, omni-channel banks if you wish, in Belgium and the Netherlands, so we’re creating one platform for 11 million customers there. And then a project that we call ‘the model bank’, which will be one platform and one way to interact for all of our clients in France, Italy, Austria, the Czech Republic and Spain.”

To bring about these kinds of sweeping changes, ING has had to rethink its culture and the way it works. Gone is working in silos and in a process-driven way that meant projects took years to reach fruition. Gone is a culture where mistakes are unacceptable, to be replaced by one in which learning from mistakes is encouraged. Most importantly, the bank sets out to disrupt itself before anyone else, such as a fintech competitor, does it to the bank.

“If you are the first one to move, if you are the first one to disrupt then, yes, you will lose some income on one side, but you will be able to compensate by growth on the other side,” says Mr Hamers. “That’s what we see when we introduce internet banking in some of the countries in which we are already a bank. We were very aggressively pricing our savings, we were disrupting our own business. But we grew much faster because we took clients from the competitors as well, so that’s the way you can actually make it work, and that’s what keeps [employees] motivated.

“The way we put it into practice is that we launch services that we know we will lose income on. For example, we launched Payconiq in Belgium, which is a payments app. That payments app takes out the use of and the need for a card system to guarantee the payments going from a consumer to a merchant, so we’re totally taking out the card scheme. We’re disrupting the card business but we’re also disrupting our own fee income from that card business, let’s face it. But I’m convinced that if we don’t do it somebody else will.”

Other recent tech wins have been the strong growth in users of the Twyp (The Way You Pay) app in Spain allowing peer-to-peer payment, and the development in Romania of Startarium, providing online resources for entrepreneurs.

Money in, money out

To maintain and further advance its technological edge, ING will invest €800m in digital banking by 2021. To ensure that this translates into returns for shareholders, the plan is to take out €900m in cost over the same period.

Mr Hamers believes that banking products do not change very much, but the way that you deliver them does. Equally you can use information gained from social media to assist in the old-fashioned task of credit scoring, enabling the bank to make very quick decisions on loan requests.

“There are many different ways that these self-learning algorithms operate, and basically you use the old-fashioned way [as well], so you will still have data from credit bureaus and your own data in the bank,” he says. “But you can also go out and see what data is out there, in terms of behaviour, in terms of statement, in terms of activities of clients and plans of clients, that they communicate about in social media. You can derive a specific pattern there, that helps you score these clients… We’re trying these kinds of algorithms to see whether we can have services that are differentiating for our clients. The only reason we do it is, if we can give you an answer to your credit request, within 10 minutes, and whether it’s ‘yes’ or ‘no’, people who get a ‘no’ are still appreciative of your service.”

But none of this is possible unless a bank can successfully change its way of working. ING claims to take ‘the agile approach, just like Spotify, Netflix and Google’. Since this approach was introduced in 2015, staff with different skill sets come together to work in squads to complete specific tasks. Once done they regroup. Private offices are a thing of the past and everyone works in a shared space.

“If you want to compete in the world of tech and if you, increasingly, want to become a tech company, you have to organise like a tech company. You have to get the culture of a tech company,” says Mr Hamers.

It is clear that by changing its way of working and its way of delivery, ING has moved the banking needle a long way forward. ING is deservedly regarded as a disruptor every bit as much as some of the fintechs on the scene. But at the end of the day it still has to conform to the stipulations of its banking licence in terms of governance and capital requirements.

While ING’s goal of creating a financial ecosystem on a single platform is eminently achievable, its ambition to be treated as tech company rather than a bank may take a little longer.