Private and investment banking move closer, not further apart

Jurg Zeltner, CEO of UBS Wealth Management

While regulators and politicians may want investment banking to be split off from private banking, in the industry the two are moving more closely together than before the crisis. But many are still predicting change in the long term.

Political pressure on banks is being stepped up, with looming threats to split risk-taking investment banking divisions from more staid wealth management and retail banking arms now firmly on the agenda.

In the UK alone, leading members of the Liberal Democrats party, part of the country's ruling coalition, have been pressing for such dramatic action since the banking crisis of 2008. Governor of the Bank of England Mervyn King has also been firmly backing such a split, with a view to preventing the re-emergence of institutions previously deemed 'too big to fail', and avoiding future bailouts.

The politicians' and regulators’ argument appears to run that if a crisis happens again, questionable structured vehicles should be allowed to go to the wall, along with their parent institutions. But the mortgages and savings of the man in the street, together with assets lodged by wealthy individuals, should be preserved in a separate, ring-fenced unit, free from contamination by the capital markets arm.

Editor's choice

This reputational risk led wealthy clients of UBS to withdraw more than SFr200bn ($219bn) in the two years following the start of the crisis, due to loss of confidence in the bank. Other banks, including Commerzbank and ING, have already been forced by regulators to separate and sell off their private banking arms to raise money to repay subsidies from taxpayers.

Integrated model

The global banks are fighting tooth and nail to preserve the commercial merits of an integrated model, where investment banking, asset management and wealth management combine for cross-selling opportunities.

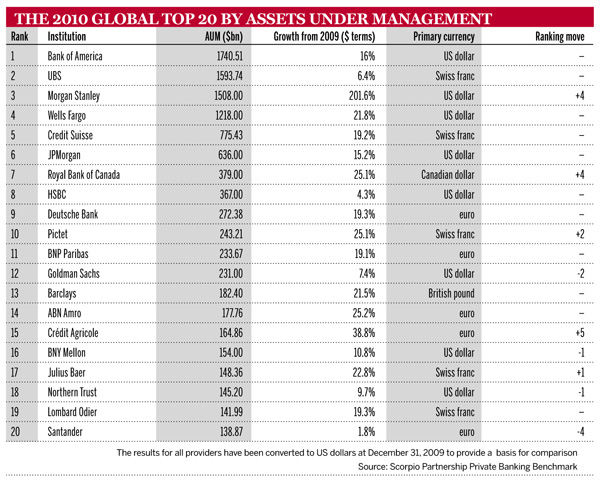

Wealth management league tables are currently dominated by those institutions that have scale and breadth of services, and this concentration is expected to continue. “People talk about global wealth management and say it’s a very fragmented market,” says Sebastian Dovey, a founding partner of wealth management think tank Scorpio partnership. “But in reality, it’s not.”

The world’s top 20 banks now control 82% of the wealth market, according to Scorpio, with 50% in the hands of 10 banks, led by Bank of America (newly merged with Merrill Lynch), UBS, Morgan Stanley, Wells Fargo (which recently joined forces with Wachovia) and Credit Suisse.

“There are 20 to 40 major, multi-market wealth managers emerging and that’s about it. This is not a permanent group, but in order to be in that group, you need to be big to even play. The constant thread is that you need both asset management and distribution, not just one or the other like it used to be.”

Jurg Zeltner, Zurich-based CEO of UBS Wealth Management, created waves when he apologised during the 2008 crisis on behalf of Swiss banks to delegates at a conference because of the incorrect marketing of structured products, created by their investment banking units, to private clients. Now he talks about a “paradigm shift” in the wealth management industry, with clients coming back with higher expectations, despite their aversion to risk.

Clients’ focus, says UBS's Mr Zeltner, whose bank sprang back from the abyss to be nominated for awards presented by The Banker and Professional Wealth Management in 2010, has shifted from “buy and hold” to dynamic portfolio structuring. This entails closer involvement of clients and their bankers in making investment decisions. His recipe for this involves further integration of private and investment banking. Crucially, his emphasis on creating more investment banking solutions for private clients, despite his recent public apology, has some traction in the industry. UBS’s investment banking arm won The Banker and PWM's Best Structured Product Provider award in 2010, with votes coming purely from private bankers. His institution’s private client assets increased 6.4% during 2009.

Pre-crisis mentality

This virtual return to a pre-crisis mentality is identical at smaller but faster-growing Zurich rival Credit Suisse, where the process of creating 'unique solutions' for private clients, based on the group’s investment banking and asset management products, has been accelerated. Both banks are beefing up specialist units, populated by highly motivated and remunerated, predominantly ex-investment bankers, to locate the best capital markets products for clients of their private banking brethren.

While this integrated model continues to strengthen within some institutions, it is regarded with some scepticism by consultants. Few large institutions will remain conducting both investment banking and commercial banking, believes Ray Soudah, a former high-ranking banker with UBS and Citigroup, now running Swiss mergers and acquisitions consultants Millenium Associates.

“Those with marginal investment banking operations will slim down or sell them and focus on the domestic home country commercial and quasi investment banking services to protect their core clients until they are finally obliged to totally exit investment banking, which has evolved as a global service handled only by a few majors,” says Mr Soudah.

He casts doubt on the assumption among bank bosses that clients benefit from having private banking integrated with capital markets activities. “It is healthier to separate private banking activities and this will occur in the very longer term,” he says, also drawing attention to the success of independent family offices, which are managing increasing tranches of ultra-high-net-worth money.

While heavily conflicted investment banks have been losing some private clients, and banks, such as Citi and Morgan Stanley, have already been divesting parts of their wealth businesses, both market forces and a lack of regulatory zeal in many jurisdictions will delay an imminent carve-up of the banks, says Professor Amin Rajan, CEO of research consultancy Create.

Challenging the orthodoxy that runs through the veins of Credit Suisse and UBS, Mr Rajan voices particular concern at how demand for structured products has been “artificially propped up by an unhealthy relationship” between wealth managers and their capital market-fuelled cousins in investment banking, searching for cheap but direct channels of distribution.

Yet despite regulatory scrutiny and increasing questioning of the one-bank model’s merits by clients in the post-credit crunch landscape, he expects a 10-year gap before any large-scale decoupling occurs.

Glacial pace of change

“The universal banking model will change, but at a glacial pace,” says Mr Rajan. “Banks wield huge political influence and any change that is detrimental to their long-term profitability will be resisted. Experience teaches us not to underestimate the subtle influence that banks worldwide exercise over their regulators. Basel III is a case in point: it won't bite in earnest until 2020. There is often a huge gap between the rhetoric and reality of banking regulation. And regulators also tend to be lax in their execution. It was not the lack of regulation that caused the credit crunch: it was sloppy enforcement.”

The Swiss regulator moved recently to strengthen its banks, in the wake of criticism following the crisis. Banks in Zurich and Geneva are now subjected to the 'Swiss finish' of higher capital adequacy commitments than institutions in rival jurisdictions.

“While shareholders would like to see a break-up of UBS and Credit Suisse, the management and regulators don’t,” says Adrian Darley, head of European equities at Ignis Asset Management and a keen follower of European banks. Instead, regulators have told Swiss bankers that if they want to compete, they must raise capital levels much higher than US and UK norms.

Both shareholders and clients are much happier with the Julius Baer “pure play” model, he says. The Zurich bank, now under the stewardship of youthful private banking boss Boris Collardi, has exited broking, trading and asset management to concentrate on its core clientele of wealthy investors. Assets handled for these clients, according to think tank Scorpio Partnership, increased by nearly 23% to $148bn during 2009.

Julius Baer won both the Best Private Bank in Switzerland and Best Private Banking Strategy for Growth accolades in the Global Private Banking Awards presented by The Banker and Professional Wealth Management magazines in 2010.

While the bank has not forgotten its home market and has been opening up new offices across Switzerland, augmented by its purchase of ING’s Geneva-based private banking arm, perhaps its most significant successes have been in Asia, named by management as Baer’s 'second home market'. A duel-centre expansion model, recruiting 400 staff, split between Hong Kong and Singapore, targets both Chinese domestic and cross-border Asian clients.

Despite Julius Baer’s undoubted achievements in Asia, it has an uphill struggle competing for talent and assets with the major US and Swiss franchises, although its recent acquisition-led growth make its newly boosted scale more persuasive.

“We reckon 90% of these big-brand operators are in Asia,” says Mr Dovey, where he pinpoints HSBC, UBS and Credit Suisse as the three equal premier private banking brands. These are followed by Julius Baer and the French banks.

Pan-Asian powerhouses

Regionally sourced candidates for pan-Asian powerhouse status still have much ground to make up before challenging the likes of HSBC, which has strong Hong Kong roots, believes Mr Dovey.

“Several years ago, we had a meeting with ICICI bank, and asked it about its ambitions,” recalls Mr Dovey, referring to India’s second largest institution, which is increasing its activities in China and across the Association of South-east Asian Nations region. “[ICICI] said to us: ‘We will be a top-five global private bank and we expect you to laugh when we say that, but why should we not be there? ABN Amro has access to a 20 million population and can get there, while we have access to 1 billion people, plus 10% of the US population, which is either non-resident Indian or has Indian links’.”

Culturally, there are strong reasons why Asian banks managing Asian money will eventually rise through the rankings, although they still have a strong battle against the US and European heavyweights. “It takes a big cultural shift for local populations to buy wealth management from non-local players,” says Mr Dovey. While both Citi and Standard Chartered have bought domestic banks in Asia, he expects Singapore's DBS, which boasts the country's government’s sovereign wealth fund as a major shareholder, to maintain independence and prosper.

“We need a much bigger template, a much bigger platform and client base,” confirms Su Shan Tan, head of wealth management at DBS, which won the award for Best Private Bank in Singapore in 2010.

This strategy is backed up by analysts in Singapore who stress that DBS must expand internationally to stay relevant in Asia. “Here in Singapore, it can’t grow any more, as it is already too large,” says Siew Hua Thio, a fund manager at Tantallon Capital, based only a few blocks from DBS's private banking operation, still preparing itself for a move to the 65,000-square-metre custom-built offices in the Marina Bay Financial Centre in 2013.

“It has to grow by entering different markets, such as Hong Kong, where it bought one of the banks. The concern for DBS is acquisition risk, plus any huge changes in top management. You are never quite clear where it is heading.”

Strong ambitions

But the DBS private banking franchise does have strong ambitions in China, Indonesia and India, with a realisation that growth must be prioritised outside its wealthy but saturated Singapore sweet-spot to achieve the ambitious five-year target of growing private client assets from $35bn to $50bn within the next three years.

Ms Tan is a celebrity character in Singapore, where she features regularly in the country’s media and sits on the boards of several hospitals, charities, schools and major home-grown companies. She is also known among her staff for attention to detail and pacing the private banking floors to pose spot tests about the nature of structured products. Staff are also encouraged to volunteer for 7.30am seminars on capital markets, product details and marketing to clients.

Although she is keen on creating Asia-centric solutions for wealthy families, she emphasises that the key aim of DBS relationship managers should be to preserve fortunes rather than double them. “We are not here to teach clients how to make a second fortune, but how to protect it, hedge it and potentially grow it for the next generation,” says Ms Tan.

While her product development team has designed the blueprint for a pan-Asian, discretionary mandate, the advisory model is still king in Asian wealth markets.

“The Asian family is typically looking for deal flow,” she says. “It has interest in initial public offerings, debt capital markets and convertible bonds.”

This increase in the advisory mentality, often identified with Asia, is not however confined to these markets, with a greater interest in tactical investing also confirmed by private banks in Europe.

Rapid response

The idea of a rapid response to fast-changing global political, macroeconomic and natural factors – such as rising unrest twinned with spiralling oil prices in the Middle East, fallout from the Japanese earthquake and ensuing economic volatility – is championed by Gerard Piasko, chief investment officer of the Swiss arm of Germany’s Sal Oppenheim, which recently has been absorbed into the growing Deutsche Bank empire.

“To ensure the diversification of different asset classes, you need to be prepared for tactical rapid responses to changing macroeconomic environments,” says Mr Piasko. His bank’s ‘Go Far’ maxim refers to focused, active, risk-oriented investing, having taken a helicopter view of the world’s various crises, before focusing on big-picture trends.

This advice is offered to all private clients, although some may not wish to take it. This approach contrasts the factory-led mentality at the Frankfurt hub of Deutsche Bank’s private and business clients unit, headed by Dominic Blum, one of the most powerful product manufacturers in the European industry.

Currently, Mr Blum’s team, which services 24 million clients across Europe and Asia, is concentrating on moving away from its former activities of recommending and frequently trading funds, supplied by the bank’s proprietary fund house DWS and a number of external strategic partners, including Schroders, Goldman Sachs, BlackRock and Invesco. The new-look, post-crisis operation focuses on constructing long-term dividend-paying portfolios from these instruments. One of the challenges in this new approach has been rebuilding the link between advisers and Mr Blum’s fund selection unit, after this was badly dented during the financial crisis.

Strengthening this link and the trust between advisers in the field and its head office has been crucial to the work being conducted with private banks by Jonathan Chocqueel-Mangan, co-founder of leadership consultancy Tyler Mangan. Before the crisis, many relationship managers were ignoring the advice and recommended product lists of their head-office bosses and taking clients into 'off-piste' products. This may have been influenced by those clients asking for complex, opaque strategies that they did not understand, but believed were making money for other private clients.

“I think it is easy to be sensationalist after the event, but the temptation to assume that everyone was acting in their self interest, contrary to the interests of all other parties, should be avoided,” says Mr Chocqueel-Mangan. “In the final analysis, I don’t think anyone comes out of this looking very good, be it head offices, advisers, customers or regulators. It transpires that all parties were colluding with a flawed system. Some of that collusion was overt and some was unintended and uninformed.”

Lessons learnt

Since these recent dark days, all parties have learned lessons and are now more informed, he believes. “Head-office recommendations are now under more scrutiny and seen as more balanced by advisers, who may be more inclined to stick to them. In turn customers are more attuned to the fact that they may not understand products as well as they thought.”

Playing a key role in changed behaviour since the crisis is regulation, including Markets in Financial Instruments Directive (MiFID) in Europe and the UK’s Retail Distribution Review (RDR).

“RDR has ensured that client advisers have far better technical skills and access to product knowledge than may have been the case beforehand. Specialist skills are now more valued and that may lead to a more virtual business model, whereby a whole range of functions are outsourced, potentially even activities such as asset management. Private banks are being forced to invest properly in systems and processes – a level of expenditure that some may not be able to afford, which may lead to a degree of consolidation in the industry,” says Mr Chocqueel-Mangan. “Wealth management groups may decide that the focus should be on the relationship, backed up by expertise and real insight into individual customer needs, and then have a very flexible delivery model behind them.”

At this time in particular, believe some consultants and practitioners, a new breed of boutique player, registering customers’ increasing dissatisfaction with commoditised advice, could emerge in the wealth management industry.

“I say to clients, if you want [upmarket UK retailer] Fortnum & Mason, go to Fortnum & Mason, if you want [UK supermarket chain] Tesco, go to Tesco,” says Louay Al-Doory, head of business development at Geneva-based family-owned boutique Reyl & Cie, and a former global head of wealth management products at UBS.

“Don’t ever be under the illusion that a big bank can give you a bespoke service. Nobody is saying that the one-bank strategy and the synergies of a big, integrated bank do not make sense. But there is always conflict. Should we not be talking more about the client than the shareholder?

“Conflicts are not good for the client. The one-bank strategies do not serve the client as well as they clearly serve the shareholder. Regulators should do more about protecting clients, not just shareholders.”