Iron ore risk leaves steel industry looking to the futures

The past couple of years have seen the pricing mechanism for iron ore changed for the first time in decades and new contracts, such as iron ore futures, launched. How effective have these changes been, asks Joanne Hart, and what impact have they had on steel prices and steel consumption, and the ability of manufacturers and producers to manage risk?

Iron ore is one of the most widely used commodities in the world. Global production last year exceeded 2.2 billion tonnes, compared with just 90 million tonnes for copper, aluminium, zinc, lead and nickel combined.

Yet, while these five metals have been traded on global exchanges for years, the iron ore market was, until recently, rooted in a system that had not changed since the 1960s. An annual price would be hammered out between dominant iron ore producers and consumers and that price would provide a global benchmark for the following 12 months. The process worked well for decades, because there was ample iron ore to meet consumers’ needs and the price scarcely moved from one year to the next.

Shaken from its torpor

In the early part of the 21st century, however, this cosy system began to fall apart. China’s exponential economic growth fuelled a need for commodities across the board, rocking raw material supply and demand dynamics.

Suddenly, iron ore prices were not holding steady, as they had done for 40 years. Instead, they were on a roll. Between 2001 and 2008, they soared from around $20 a ton to $180 a ton. Annual benchmarking no longer seemed such a clever idea, particularly to large producers such as BHP Billiton, Rio Tinto and Vale, who were losing billions of dollars a year to their customers. Iron ore is a key ingredient of many types of steel so these customers were principally steel producers.

Tensions mounted as steel-makers battled to retain the old system and iron producers fought for change. Then, at the end of 2008, the financial crisis sent prices plummeting. Iron ore fell back to $60 a ton, a move which highlighted the metal’s new-found volatility. Prices began to rise again at the end of 2009 but by that stage, the annual benchmarking process was in crisis as the big producers turned their backs on the old ways. Since then, index-based pricing has increasingly become the norm. But index-based pricing only works with reliable indices – and these did not exist until relatively recently.

“Indices used to be compiled quite informally on a monthly basis. But from 2004 onwards, volatility increased sharply and it was clear that a more robust index was needed,” says Tim Hard, a director at The Steel Index (TSI), one of the most widely used iron ore indices.

TSI uses data from 500 providers to compile daily indices for iron ore and related products. Iron ore is a key ingredient of hot rolled coil – the steel used to make products ranging from cars to washing machines, and it can be a component of other forms of steel too – billet and rebar – which are used for construction. When iron ore prices rise, therefore, there are serious consequences for manufacturing and industry around the world.

Widespread impact

“Iron ore and other raw materials used to account for 40% of the cost of hot rolled coil. Now they account for about 70%,” says Colin Hamilton, senior analyst at Macquarie.

This shift has transformed the dynamics of the steel industry. “As raw materials costs now account for more than 50% of the price, so the nature of the steel-making sector has changed. It has become more of a conversion business than a value-added one,” says Mr Hamilton.

The steel market is vast. In terms of value, it is the second largest commodities market in the world, after oil. When the industry is under pressure, therefore, the repercussions can be felt across the globe. In the past, the benchmark system might have offered some protection to steel makers. Now, they are far more exposed to the impact of soaring input costs on their prices and their profit margins. And input costs are unlikely to come down, as long as Chinese economic growth continues, fuelling demand for raw materials such as iron ore.

“China used to account for 10% of global iron ore sales. Now it mops up about 60%,” says Ray Key, global head of metals trading at Deutsche Bank.

Market volatility

This dramatic increase has made iron ore and steel markets far more volatile.

“Volatility has increased four-fold in the steel industry since 2004. Demand has soared and the supply chain has struggled to keep pace. The resulting shortages have provoked spikes in the price, although any hint of a surplus in supply has then sent prices down quite sharply. We believe demand will continue to grow over the next five years and there will be short-term shortages along the way, which means volatility will persist,” says Paul Scott of metals consultancy CRU.

Volatility is rarely welcomed by manufacturers and the speed of change in the steel industry has been particularly unnerving. For financial markets, however, the situation has created a clear opportunity. Over the past three years, futures contracts have been developed in all the major financial centres to help steel and iron ore players manage their risk.

“Steel producers have a choice. They can absorb the volatility of iron ore prices. They can pass it on to their customers or they can hedge it. We are one of the biggest lenders to industrial companies in Europe and we have seen a tremendous increase in the number of hedging enquiries related to iron ore and steel. Previously, companies were effectively hedged for one year out, through the annual benchmark system. Now they are exposed to floating prices so they need more risk management tools,” says Mikko Rusi, Europe, Middle East and Africa head of metals sales at BNP Paribas.

Some industry participants are more engaged with the financial markets than others. “We expected demand to come primarily from Asia but we have been surprised how much pressure there is from the European manufacturers on steel mills to promote the growth in steel and iron ore contracts in order to manage their risk,” says Mr Key.

“Big industrial companies, such as car-makers or white goods manufacturers have a huge exposure to steel and many of them are already familiar with hedging because they do it for copper, aluminium and zinc so it is a logical progression,” adds Mr Rusi.

Trading interest

Traders also see the advantage in hedging prices. “If a company is shipping iron ore from South America and selling it three months later in China, it makes real sense to lock in prices and gain certainty,” says Mr Rusi.

A number of contracts have been created by exchanges, including the Chicago Mercantile Exchange for hot rolled coil and iron ore, the Singapore Exchange for iron ore and the London Metal Exchange (LME) for billet. Billet is generally made from ferrous scrap, prices of which have also become immensely volatile in recent years.

“The development of futures contracts for ferrous metals enables the steel industry to manage volatility and bring stable prices to their customers,” says Chris Evans, head of business development at the LME.

Interest is certainly growing since the contracts were launched in 2008. In that first year, 1 million tonnes were traded. Volumes doubled in 2009 and surged to 10 million tonnes in 2010. Of that amount, 1.1 million tonnes were traded in the first quarter. This year, volumes more than tripled to 4.5 million tonnes in the first three months.

The figures are moving in the right direction but they still represent a tiny fraction of global billet trade.

“Some people are already familiar with risk management tools but for others, the concept of futures is new and it takes some getting used to, especially as the need has not existed historically. It always takes time for new contracts to bed down. Aluminium and nickel took 10 years but steel volumes are growing each month,” says Mr Evans.

The LME is also looking at a range of other products in consultation with its members, which include most of the major participants in metals and mining. “We are actively looking at other steel products and our members are developing them with us. Iron ore is also on our radar screen,” says Mr Evans.

Volume growth

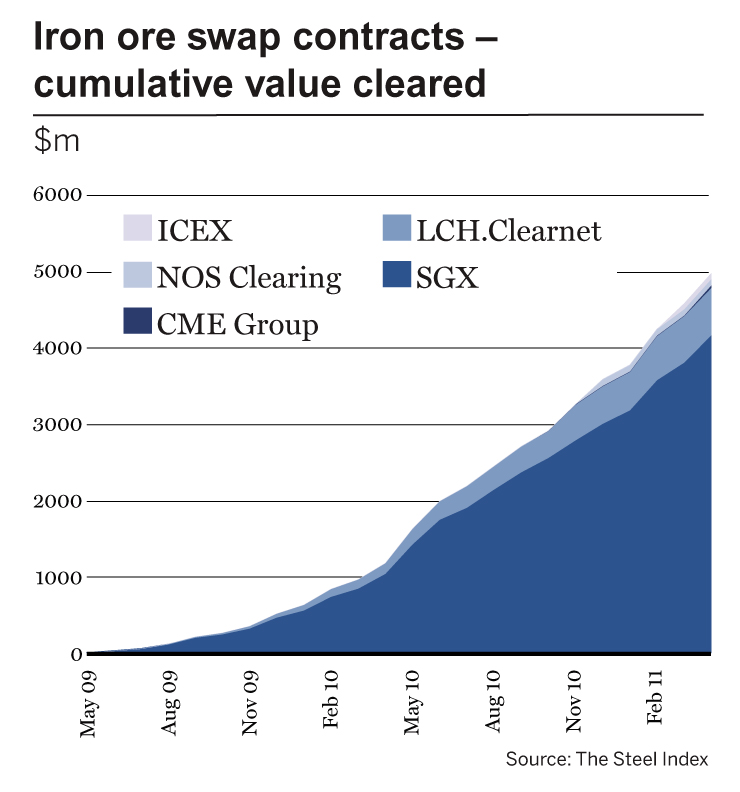

The LME’s interest in iron ore is understandable. Other exchanges already involved in this market are seeing volumes growing fast. “More than $5.5bn of iron ore swaps have been cleared since launch last May, using the TSI index. The market is still in its infancy but it is growing quickly,” says Mr Hard.

In the last week of April, for example, the Singapore Exchange cleared iron ore swaps equivalent to 892,500 tonnes of the metal, a weekly record and 20% ahead of the previous weekly high. Smaller iron ore producers are showing a keen interest in futures contracts, seeing a real use for them as the market moves from benchmark to floating prices.

“The major development over the past year has been project-related hedging. Smaller mining companies looking for finance can get more attractive borrowing rates from their banks if they fix the forward prices for a portion of their production. The typical share of hedging is 25% to 40% of production over the life of a loan. Fixing a portion of revenues in advance gives banks confidence that the company will be able to repay the loan even if prices fall,” says Kamal Naqvi, global head of institutional commodity sales at Credit Suisse.

“Longer-dated price fixing could not have occurred before the introduction of index-based pricing. And that is the big advantage of liquid, forward, visible and transparent paper markets,” he adds.

Mr Naqvi points out that, even though benchmark pricing offered a measure of stability for up to a year, there was no pricing visibility beyond that time frame. Credit Suisse is now offering prices out to 2013 and occasionally even further ahead. Small iron ore producers are responding to these offers but financial players are coming into the market too.

“We are beginning to see interest from hedge funds and pension funds. Some hedge funds, for example, are looking to buy or sell iron ore futures to hedge against equity positions in resource companies,” says Mr Naqvi.

Fresh deals

New contracts are springing up too. The first ferrous scrap swap was traded in April and there are wide expectations that this sector will develop fast, given scrap’s importance in the steel value chain.

While some contracts are traded on exchange, many more trade over-the-counter (OTC), often in bilateral agreements between banks and their industrial customers. “OTC markets are more discreet and more flexible,” says Mr Scott.

Interest in these contracts is clearly growing but pockets of resistance remain, particularly among steel producers, who look back nostalgically to the old ways. Intriguingly however, some major users of steel are going straight to the futures markets to lock in raw materials costs. They then offer steel producers a margin above those costs.

“If the steel price is $600, for example, and the primary raw materials [iron ore and coking coal] account for $400 of that, a customer can fix the raw material costs and agree to pay a fixed processing margin to the steel mill. Some of the larger, more sophisticated steel consumers show a high level of interest in this approach to hedge a key input cost,” says Mr Naqvi.

China concern

Over the next few years, this type of activity is likely to become increasingly common, particularly if volatility persists or intensifies. But, for steel and iron ore futures to take off in earnest, there needs to be global participation. And despite growing interest in these new instruments, many banks have been concerned by the attitude of the Chinese, the largest consumers of both iron and steel.

Until recently, the Chinese have been among the fiercest opponents to change. Encouragingly for financial players, however, they are beginning to come round. At one time, for example, Chinese steel mills were banned from using financial swaps. Now the rules are being relaxed. “Chinese mills and traders are reportedly starting to test the iron ore swap market through the Singapore Exchange,” says Mr Naqvi.

Intriguingly too, the Shanghai Exchange has developed a highly liquid market in rebar futures. Rebar is produced from billet and the Shanghai futures market in this metal has been developed with Chinese manufacturers’ interests in mind. They have shown a real interest in these risk management tools, in contrast to Chinese steel mills, whose acceptance of iron ore futures has been slower and more sporadic. So, while steel mills gradually come to terms with new pricing methods, Chinese rebar traders are adapting to change with enthusiasm.

“There are signs that purchasing decisions are beginning to be made based on the rebar forward curve in China,” says Mr Scott.

Encouraging actions

This kind of development is hugely encouraging for financial players. Steel and iron ore markets are huge, global and highly volatile. Industry players are beginning to understand the benefits of futures as a risk management tool but activity is still tiny when compared to the size of these markets overall. Financial markets will never dictate prices, nor do they aim to, but they can help companies manage their risks more effectively and allow them to plan more efficiently for the future. Importantly too for banks, brokers, exchanges and index providers, steel and iron ore are a potentially huge source of revenue.

“Strong, liquid iron and steel futures can be transformative for banks involved in these markets,” says Mr Rusi.

Across the financial community, there is a widespread belief that iron ore producers, steel mills and steel end-users will increasingly turn to the futures markets over the next three to five years. Volatility shows no sign of disappearing and contracts are on offer to help industrial users manage the changing patterns. For many years, steel and iron ore were the only bulk commodities to be traded without derivatives. For many years, derivatives were unnecessary for these two industries. Now the environment has changed.

“A level of risk has been introduced into these markets. It is important for anyone involved in iron ore or steel to respond to the change” says Martyn Whitehead, head of metals and mining sales at Barclays Capital.